![Praying for Sleep]()

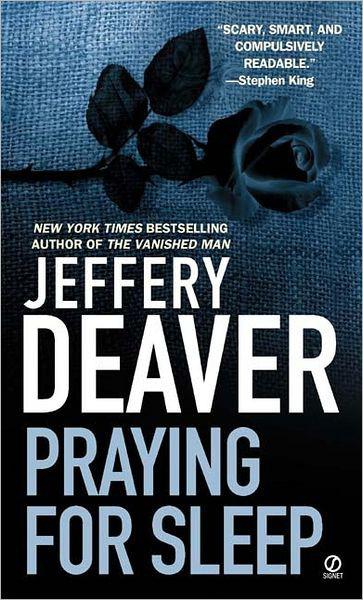

Praying for Sleep

else—even in his dark tiny office, where he would often spend fifteen straight hours. His pulse was high, his limbs itched from this fear of confinement and he was having trouble breathing. He also heard noises where no noises should be and his sense of direction was terrible. He was on the verge of admitting to himself that, yes, he was lost. His points of reference—trees, signposts, bushes—were vague and shifty. More often than not, as he walked toward them, they simply vanished; sometimes they turned into grotesque creatures or faces in the process.

Over his shoulder was his ruddy backpack, containing the syringe and drugs, and on his arm was a black London Fog raincoat. He was too hot to wear it and he wondered why on earth he’d brought the coat with him. The radio updates about the impending storm suggested that a helmet and armor would be better protection than gabardine.

Kohler had parked his BMW up the road, a half mile from here, and had made his way through a field into this forest, making slow progress. His leather soles slipped off the damp rocks and he’d fallen twice onto the hard ground. The second time he’d landed on his wrist, nearly spraining it. The vicious thorns of a wild rosebush hooked his pant leg and it took five painful minutes to free himself.

Kohler recognized, though, that he’d been lucky. The nurse who’d alerted him to the escape reported that the young man had run from the hearse in Stinson and had apparently gotten as far as Watertown.

As Kohler had sped in that direction down Route 236, he was certain that he’d sighted Michael in a clearing. The doctor raced to the turnoff, climbed from the car and searched the area. He’d called his patient’s name, pleaded with him to show himself, but received no response. Then the doctor had driven off once more. But he hadn’t gone far. He pulled off onto a side road and waited. Ten minutes later he believed that he’d seen the same figure hurrying on once more.

Kohler had found no sign of Michael since. Hoping he might stumble across him by chance, the psychiatrist had taken to the wilderness again, heading in the direction in which Michael seemed to be headed—west.

Where are you, Michael?

And why are you out here tonight?

Oh, I’ve tried so hard to look into your mind. But it’s as dark as it ever was. It’s as dark as the sky.

He tripped again, on a strand of wire this time, and tore his slacks on a sharp rock, gouging his thigh. He wondered if there was a danger of tetanus. This thought discouraged him—not the risk of disease but the reminder of how much basic medicine he’d forgotten. He wondered if his knowledge of the human brain compensated for the long-forgotten facts of physiology and organic chemistry he once had learned and recited so easily. Then these thoughts faded, for he found the sports car.

There was nothing remarkable about the vehicle itself. He didn’t for a minute think that Michael had lifted the hood and tried to hot-wire it. His patient would be far too frightened at the thought of driving a car to steal one. No, Kohler was intrigued by something else—a small object resting on the ground behind the rear bumper.

The tiny white skull ironically was the exact shade of the car itself. He stepped closer and picked it up, looking carefully at the delicate bones. A tiny fracture ran through the cheek. Trigeminal, he thought spontaneously, recalling the name of the fifth pair of cranial nerves.

Then the skull teetered on the tips of his fingers for an instant and tumbled with a soft crack onto the trunk of the car, rolling into the dust of the shoulder. Kohler remained completely still as the muzzle of the pistol slid along his skin from his temple to his ear, while a fiercely strong hand reached out and fastened itself to his shoulder.

13

Trenton Heck pointed the Walther up at the turbulent clouds and eased the ribbed hammer down. He put the safety on and slipped the gun back into his holster.

He handed the wallet back to the skinny man, whose hospital identification card and driver’s license seemed on the up-and-up. The poor fellow wasn’t quite as pale as when Heck had tapped the muzzle to his head a few minutes before.

But he wasn’t any less angry.

Richard Kohler dropped to his knees and unzipped the backpack Heck had tossed onto the grass before frisking him.

“Sorry, sir,” Heck said. “Couldn’t tell whether you were him or not. Too dark to get a good look, with

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher