![Ptolemy's Gate]()

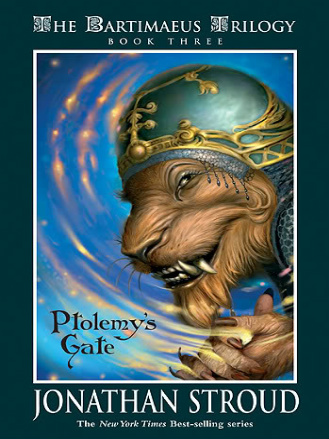

Ptolemy's Gate

the other ministers—most of whom wished him harm. His only close associate, for a time, was the hack playwright Quentin Makepeace, as self-serving as all the rest. To survive in this friendless world, Mandrake cloaked his better qualities under layers of smarm and swank. All his old life—the years with the Underwoods, his vulnerable existence as the boy Nathaniel, the ideals he'd once espoused—was buried away deep down. Every link with his childhood was severed, except for me. I don't think he could bring himself to break this last connection.

I proposed this theory in my usual gentle way, but Mandrake was unwilling to listen to my taunts. He was a worried man.[9] The American campaigns were vastly expensive, the British supply lines overstretched. With the magicians' attention diverted, other parts of the Empire had become troublesome. Foreign spies infested London like maggots in an apple. The commoners were volatile. To counter all this, Mandrake worked like a slave.

[9] I'm stretching the term a bit here, I know. By now, in his mid to late teens, he might just about have passed for a man. When seen from behind. At a distance. On a very dark night.

Well, not literally like a slave. That was my job. And a pretty thankless one it was too. Back at Internal Affairs, some of the assignments had been almost worthy of my talents. I'd intercepted enemy messages and deciphered them, given out false reports, trailed enemy spirits, duffed a few of them up, etc. It was simple, satisfying work—I got a craftsman's pleasure from it. In addition, I helped Mandrake and the police in the search for two fugitives from the golem affair. The first of these was a certain mysterious mercenary (distinguishing features: big beard, grim expression, swanky black clothes, general invulnerability to Infernos/Detonations/pretty much everything else). He'd last been seen far away in Prague, and predictably enough we never got a whiff of him. The second was an even more nebulous character, whom no one had even set eyes on. He apparently went by the name of Hopkins, and claimed to be a scholar. He was generally suspected of masterminding the golem plot, and I'd heard he'd been involved with the Resistance too. But he might as well have been a ghost or shadow for all the substance we could pin down. We found a spidery signature in an admissions book at an old library that might have been his. That was all. The trail, such as it was, went cold.

Then Mandrake became Information Minister and I was soon engaged in more depressing work, viz. pasting up adverts on 1,000 billboards across London; distributing pamphlets to 25,000 homes across ditto; corralling selected animals for public holiday "entertainments";[10] supervising food, drink, and "hygiene" for same; flying back and forth across the capital for hours on end trailing pro-war banners. Now, call me picky, but I'd argue that when you think of a 5,000-year-old djinni, the scourge of civilizations and confidante of kings, certain things come to mind—swashbuckling espionage, perhaps, or valiant battles, thrilling escapes and general multipurpose excitement. What you don't readily think of is that same noble djinni being forced to prepare giant vats of chili con carne for festival days, or struggling on street corners with bill-posters and pots of glue.

[10] Following the Roman tradition, the magicians sought to keep the people docile with regular holidays, in which free shows were put on in all the major parks. Lots of exotic beasts from across the Empire were displayed, as were minor imps and sprites allegedly "caught" during the war. Human prisoners were paraded along the streets, or enclosed in special glass viewing globes in the St. James's Park pavilions for the populace to jeer at.

Especially without being allowed to return home. Soon my periods of respite in the Other Place became so fleeting I practically got whiplash traveling there and back. Then, one day, Mandrake ceased dismissing me altogether, and that was it. I was trapped on Earth.

Over the next two years I grew steadily weaker, and just when I was hitting rock bottom, scarcely able to lift a poster brush, the wretched boy began sending me out on more dangerous missions again—fighting bands of enemy djinn that Britain's many enemies were using to stir up trouble.

In the past I'd have had a quiet word with Mandrake, expressing my disapproval with succinct directness. But my privileged access to him was no more.

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher