![Rachel Alexander 02 - The Dog who knew too much]()

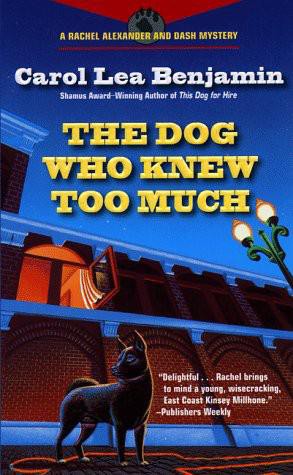

Rachel Alexander 02 - The Dog who knew too much

things—but safe isn’t one of them.

So while Dashiell played, I paid attention. Once I saw that things looked benign, I let my eyes wander, noticing a young man practicing t’ai chi on the grassy area just to the west of the run. I had once seen a young woman practicing there. I wondered if it might have been Lisa.

In China , Avi had told me when we took a break from practicing the form, people always practiced out of doors. Groups of hundreds of people gathered in the early morning, before going to work, and in the evening, on their way home, to do the form in a sea of shared energy. Most Americans practiced alone, as Lisa must have, Lisa who had wanted to go to China but had gone only in her imagination.

I got up, walked to a comer of the ran , faced north, and practiced whatever I could remember from years earlier and the night before.

An hour later Dash and I headed for the West Village Fitness Club, on Varick Street , a short walk from Lisa’s apartment. The Club, as it was called, had a twenty-five-meter indoor pool. I suspected that it was where Paul and Lisa had met.

As I entered the cavernous space, the pool was down a flight of stairs on the left. I could smell the chlorine. The aerobic equipment and weight machines were in a large mirrored room off to the right. The health bar, where Paul Wilcox had said to ask for him, was straight back.

I walked up to the young man who was standing near a display of high colonics making carrot juice and politely waited for him to notice me. To my surprise, he was practically naked, though if I looked half that good, I too might walk around wearing nothing but a tiny orange bikini. He was my height, maybe an inch or two taller, my age, maybe a year or two younger, and looked to be about 155 pounds soaking wet, which he was, his hairless body the color of jasmine tea.

“Would you like a carrot juice?” he asked over the sound of the juicer. His almond-shaped eyes, mysteriously hooded beneath epicanthic folds, were the color of melted bittersweet chocolate.

It was the voice from the telephone. Sounded like Queens . Must be ABC, I thought, American-born Chinese.

“Paul Wilcox?”

“The cousin?”

“Rachel,” I said, reaching out my hand.

He didn’t take it.

“Funny she never mentioned you,” he said, pouring the hideous-looking brown juice into two glasses, “but I can see the family resemblance.”

“Yeah?”

Cool, I thought.

“Yeah. It’s really strong.” He took off his round, metal-rimmed glasses and stared at me. “Your coloring is different. Lisa’s was more extreme—whiter skin, darker hair. But you have the same body type, the same-shaped face, the same wild hair.”

Apparently the ancient rules of politeness had gotten lost in translation.

He walked around to the front of the counter and stood next to me. “And you’re the same height.”

He was barefoot.

“The same shoe size, too,” I told him.

“So, are you like her in other ways?” he asked, carefully putting his glasses back on.

“Yeah. We were identical cousins.”

“Then you speak Chinese?”

“Not a word. How about you?” I asked.

“Not a word,” he said. “I’m only half Chinese, in case you were puzzled by the name.”

I shrugged one shoulder, as if to say, hey, you wanna be half Chinese, what’s it my business.

“An identical cousin,” he said. “Another swimmer?”

“Dog paddle. Olympic quality.”

“You hide your grief well,” he said.

“Thanks. According to the Talmud, the deeper the sorrow, the less tongue it hath.” I emphasized the th .

“Ah, another scholar in the family. That’s just the sort of thing she might have”—he took a swig of juice—“said,” he said, studying me.

I studied him right back.

I remembered a trick Ida had shown me, the time she asked me to bring my family album to a therapy session. She had placed her hand over the top half of people’s faces, my mother’s, my father’s, Lili’s , and mine, to show their smiling mouths. Then she’d slid her hand down and covered the mouths, exposing the tops of the faces. Without the smile, something else showed. I looked afraid. Lili looked defiant. My mother’s eyes looked angry. My father’s eyes looked sad beyond belief. Like Paul Wilcox’s dark eyes.

He handed me one of the glasses of rust remover and led the way to one of the little bistro tables next to the juice bar.

“My cousin and I weren’t close,” I confided. “You know how it

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher