![Rachel Alexander 02 - The Dog who knew too much]()

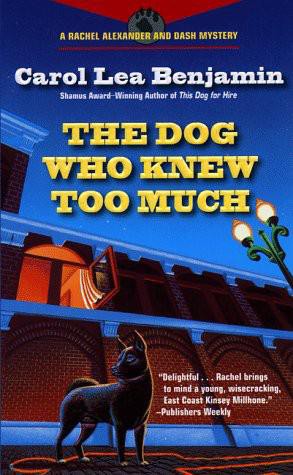

Rachel Alexander 02 - The Dog who knew too much

then silently berated myself for the frivolous thought.

Driving home along the Belt Parkway , I couldn’t get the image of Lisa Jacobs’s mother out of my mind. For that’s what she was, first and foremost, the devoted Jewish mother of a beautiful, blue-eyed, curly-haired thirty-two-year-old who ten days earlier, with no clues to foreshadow the act, had opened one of the oversize windows at the t’ai chi studio where she studied and taught and jumped five stories to her death.

“We want to show you our Lisa,” Marsha had said, welcoming me into the living room time forgot. “Come and sit, Rachel. Can I get you some tea?”

“Thank you,” I said, feeling chilled by the room and my wet clothes. Dashiell had body-slammed me several times right before we left the beach, and my leggings felt as if I had been in the ocean, too. I wondered if we’d each get a different pattern of bone china from which to drink our tea, like the cups my mother had collected.

David Jacobs was sitting on one side of the couch, a thick, leather-bound photo album on his lap. He patted the middle seat, and hoping I wouldn’t leave a big, wet ass print on their sofa, I sat next to him.

“This has been very hard on her,” he said as soon as Marsha had left to make the tea. “She—” he began, but then hesitated. “She’s up all night,” he whispered, “pacing, pacing. She’s driving me crazy. She—” he sighed before correcting himself—“we, we,” he repeated, “ would like you to help us, Rachel. We cannot understand what could have possessed Lisa, what made her do this awful thing.” He sounded angry. “We don’t have a guess. Not a clue.”

David placed the album on the coffee table, stood, and went to get his cigarettes from the top of the piano. His suit pulled across his potbelly and hung too loosely around his arms and shoulder's , as if he had recently lost a good bit of weight, a supposition that, considering the circumstances, I would not have had to be a detective to make.

“Lisa never complained, never complained. She never spoke of any problems. She was always cheerful, kind, a happy girl. Ach,” he said, stopping to light his cigarette, “how could this have happened? We gave her everything.”

I could hear Marsha talking to Dashiell in the kitchen, where she’d suggested I stash him, even though he had already stopped dripping by the time we’d arrived. Dashiell’s tail tapped out his answer on the tile floor.

“She was studying to be a Zen Buddhist priest, my Lisa,” Marsha said, standing in the archway at the rear of the living room. “The study and the t’ai chi gave her peace. Peace. That’s what she told her father and me. So why—”

“Sit, Marsha,” David said, blowing smoke into the middle of the room. Marsha sat next to me. Now I had their grief on both sides. In our silence we could hear the kettle whistle, and Marsha left again to make the tea.

“Are you cold, Rachel?” David said, as concerned as if I were his daughter.

“No, no,” I lied, “I’m fine.”

“Are you sure? Marsha, bring her a sweater,” he shouted in the direction of the kitchen.

“No, thank you, I’m fine. Really.”

“It’s no trouble,” he said, half to himself. “We have plenty of sweaters.”

He moved the album closer but didn’t open it.

“Ceil said you used to be a dog trainer. Before.”

I raised my eyebrows.

David looked at me and puffed on the cigarette, ashes dropping onto his suit pants. “Before your—before you were married.” He brushed at his trousers, leaving a dry, gray trail where the ashes had been.

Marsha arrived with the tray and placed it carefully next to the photo album. She handed me a cup with yellow tulips on it and gave David one with purple irises, saving the one with the tiny red rosebuds for herself .

“Marsha—the sweater, the sweater,” David said impatiently.

Suddenly I had the eerie feeling I was in some relative’s suffocating home. I reached for a cookie. Marsha returned with a navy blue sweater and handed it to David, who handed it to me. I put it over the arm of the sofa.

“So—” David said. “You married again? Your husband approves of this kind of work, detective work?”

Marsha was biting a small biscuit. She looked up, curious.

Ceil would have told them I hadn’t married again, wouldn’t she?

I reached for another cookie. “Lisa was single, wasn’t she?” The eighth law of private investigation, according to my

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher