![Rachel Alexander 02 - The Dog who knew too much]()

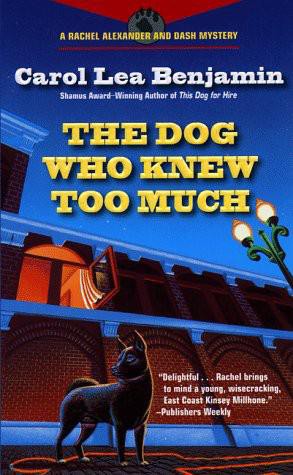

Rachel Alexander 02 - The Dog who knew too much

guess,” he said. Four years old.

“So you were crying because Lisa was going away?”

Howie nodded.

“And when your mother got after you, you gave her a good reason for the tears, one that would shut her up.”

He nodded again. “She didn’t know about Lisa and me being friends. She wouldn’t have much liked it, so I never told her .“

“What would her objection have been?”

“She says I don’t do enough for her,” he said. “She doesn’t want me wasting my time on other people when my own mother is sitting alone all day, rotting out, as if she didn’t have a son to take care of her in her old age. She’s not even that old,” he said. “People still work, they live alone, at her age.”

“Oh, Howie. No son could do more than you do.”

He looked surprised, then pleased. “You look so much like her,” he said, “it’s almost like she’s s-sitting here with me.”

“Lisa?”

He nodded.

“I used to talk to her here, just like this.” Howie ate some fries, then picked up his hamburger and just held it in his hand.

“When no one else was around?”

He nodded.

“Yeah. Lisa worked late a lot. Sometimes I’d come over and help her out, and then she’d let me”—he stopped and looked around— “unload. That’s what she used to say to me, Rachel. Howie, you’re carrying a building on your shoulders, you need to unload. Sit here and tell me your troubles.” The tears began in earnest, but Howie didn’t seem to notice. “When I’d talk to Lisa about my mother, it wouldn’t seem so b-bad. She’d tell me, like you did, how good I was to take care of her, and I’d feel better, feel I could d-do it. But now, now with Lisa gone, sometimes I can’t stand it, and I don’t know what to do. There’s no one else to d-do it but me. What choice do I have? And I do it, I do the best I can, but nothing s-satisfies her. The b-b-bitch won’t let me breathe, she’s on me day and night.”

“How’d you get stuck with her, Howie? What happened to your father? Where’s he?”

Howie stood so quickly, the couch moved back and hit the wall with a thud. His eyes were burning holes in me, his face a tapestry of rage.

I heard another noise, coming from the direction of Avi’s office. Then Howie began to come around the table toward me.

Ch’an came slowly toward us, her head down, her small, triangular ears alert, staring at Howie.

“Sit down, Howie,” I whispered. “ Now .”

Howie sat trembling on the couch, unable to take his eyes off the Akita .

“N-never l-liked me,” he said.

Did he mean Ch’an ? Or his father?

Ch’an lifted her nose in the air, then headed straight for the hamburger in Howie’s hand.

“Tell me about it,” I said, breaking off a piece of my burger, taking a bite, and offering the rest to Ch’an . For a moment, my whole hand disappeared into her mouth, but she took the food gently, releasing my hand unharmed. “Come on, Howie, talk to me. You know you want to.”

He took a wad of tissues out of his pocket and wiped his eyes. “He left when I was s-seven. Just w-walked out.”

“And you never saw him again?”

Howie flushed.

“Did you ever see him again after that, Howie?”

“Once,” he said. “He came b-back a year later, just showed up at the d-door. ‘Tell your m-mother I’m here, son,’ he said. So I left him there, in the doorway, and went to tell my m-mother. She said, ‘ You go tell that b-bum we’re not interested. Tell him to go away and this time, don’t come b-back.’ ”

“And what did you do?”

“What she said. I always do what sh -she says,” he shouted at me. “You met her!”

“So you did what she said?”

“I d-did. I told him to go away. And not come b-back. Only now,” he said, tears falling from his basset hound eyes, “now she says to me, ‘Who’s to take care of me but you, Howie? You’re all I’ve got, son. Thanks to you!’”

I was going to ask why his sister wasn’t sharing the responsibility of taking care of Dora. But hadn’t I been too busy with work when my own mother had needed care? Doesn’t the burden of a sick or aging parent often, for one reason or another, fall to one person instead of being shared?

“Then yesterday,” Howie shouted, before I had the chance to ask him anything, “I couldn’t take it anymore. It was too much pressure. I ran out of the house. I didn’t even take my jacket. I walked all the way up to Forty-eighth Street before I noticed where I was.

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher