![Right to Die]()

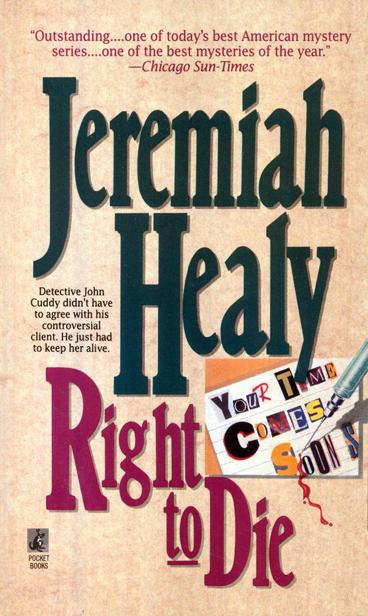

Right to Die

on her.”

“Christ. Rape?”

“Uh-uh. But this was four, five years ago, when the heat was on for those kinda things, so I get sent with the uniforms. When she opens the door for us, here’s this Strock guy, half into his pants.”

“He was in her apartment?”

“Yeah. Seems he gave her a song and dance about feeling sick or something, and she bought it. Anyway, here’s this guy, and he’s drunk, weaving and stumbling with the pants and the belt coming through the loops and all, trying to make like everything was okay. Kinda pathetic.”

“What happened?”

“Oh, nothing. What do you think? Nobody decided to press nothing. Wouldn’t even have remembered the guy, but you asked me and the sheet registered, that’s all.”

“Anything on O’Brien?”

“Not yet. Be a day or two. Call me.”

“I will.”

“For lunch.”

My turn to swallow. “Looking forward to it.”

Providence lies about forty-five minutes south of Boston. There’s a point, a few miles north of the city, where 1-95 hooks just right near the top of a hill, and you catch an imposing view of the statehouse. Huge white dome like the Capitol in Washington , a pillared mini-temple at each point of the compass.

Downtown Providence is stolid rather than showy but has probably the best indoor athletic facility in New England, the Providence Civic Center . I stopped to check in at police headquarters across from the center. It was change of shifts, a lot of brown and beige uniforms heading out, like United Parcel drivers wearing sidearms. I’m not licensed in Rhode Island , but usually nobody would question that. If they do, it’s a good idea to have checked in first with the local department. A real good idea.

The desk sergeant also gave me impeccable directions to the address I wanted.

There was no answer when I pushed the button in the vestibule of Steven O’Brien’s apartment building. There were sixteen mailboxes, a glimpse of at least one envelope through the slot with his name on it. I went back out to the Prelude to wait.

For the second time that day, I was glad to have a book with me.

About an hour later a man came walking down the street, taking out a snap case and carefully shaking free a mailbox key. Roly-poly, he wore a blue insulated Wind-breaker, the bottom of a light green tie trailing almost past the fly in his dark green pants. I got out of my car as he turned and pulled open the glass entrance door. He had just put his key into the right mailbox lock when I slipped through the door behind him.

O’Brien looked up suspiciously. Doe eyes, thinning black hair, the first person in years I’d seen with dandruff flakes on his shoulders. When he was young, I bet the other kids called him “Stevie,” stretching the first syllable.

“Who are you?”

Paul Eisenberg was right about O’Brien’s voice. Like an altar boy on Palm Sunday. “John Cuddy.”

I flashed my ID, but he never even glanced at it.

“What do you want this time?”

I ran with it. “Same as last time. Upstairs or a ride?”

O’Brien sighed resignedly. “Upstairs, I guess.”

Ascending two flights, I followed him partway down one dim and scuffed corridor. Using three different keys on the locks to his apartment door, O’Brien nearly put his shoulder through it to overcome some warping.

We entered on the living room. There was an old cloth couch outclassed by a leather chair that would have been a showpiece in 1945. A twelve-inch black-and-white stood on a trestle table that was too big for the television.

O’Brien took off his Windbreaker, having to shrug and tug to clear his elbows. Underneath, he wore a V-neck sweater vest, the shirt badly discolored under the arms. He walked toward the chair, motioning me toward the couch.

I said, “I’ll take the chair instead.”

With a sour look, O’Brien moved to the couch. Sitting, he said, “You know, I have a First Amendment right to send those letters.”

In an even voice I said, “Tell me about it.”

“What do you care?”

“Try anyway.”

“The bishop isn’t doing a thing, not a solitary thing, about the abortion issue. How can he expect me to sit still while God’s children are being murdered?”

O’Brien threw me. “Does that mean you had to send the letters?”

“Of course it does. How can I get noticed otherwise? I’m a bookkeeper, for heaven’s sake. I don’t have brazen anchorwomen wanting to interview me. I don’t have any access, even to my own

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher