![Rizzoli & Isles 8-Book Set]()

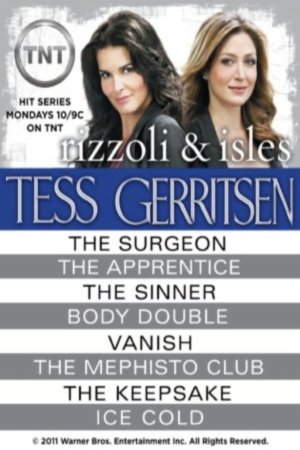

Rizzoli & Isles 8-Book Set

a necessary evil.”

“Necessary for whom?”

“Our survival as a museum. Since the article about Madam X, our ticket sales have gone through the roof. And we haven’t even put her on display yet.”

Robinson led her into a warren of hallways. On this Sunday night, the Diagnostic Imaging Department was quiet and the rooms they passed were dark and empty.

“It’s going to get a little crowded in there,” said Robinson.

“There’s hardly space for even a small group.”

“Who else is watching?”

“My colleague Josephine Pulcillo; the radiologist, Dr. Brier; and a CT tech. Oh, and there’ll be a camera crew.”

“Someone you hired?”

“No. They’re from the Discovery Channel.”

She gave a startled laugh. “Now I’m

really

impressed.”

“It does mean, though, that we have to watch our language.” He stopped outside the door labeled CT and said softly: “I think they may be already filming.”

They quietly slipped into the CT viewing room, where the camera crew was, indeed, recording as Dr. Brier explained the technology they were about to use.

“

CT

is short for ‘computed tomography.’ Our machine shoots X-rays at the subject from thousands of different angles. The computer then processes that information and generates a three-dimensional image of the internal anatomy. You’ll see it on this monitor. It’ll look like a series of cross sections, as if we’re actually cutting the body into slices.”

As the taping continued, Maura edged her way to the viewing window. There, peering through the glass, she saw Madam X for the first time.

In the rarefied world of museums, Egyptian mummies were the undisputed rock stars. Their display cases were where you’d usually find the schoolchildren gathered, faces up to the glass, every one of them fascinated by a rare glimpse of death. Seldom did modern eyes encounter a human corpse on display, unless it wore the acceptable countenance of a mummy. The public loved mummies, and Maura was no exception. She stared, transfixed, even though what she actually saw was nothing more than a human-shaped bundle resting in an open crate, its flesh concealed beneath ancient strips of linen. Mounted over the face was a cartonnage mask—the painted face of a woman with haunting dark eyes.

But then another woman in the CT room caught Maura’s attention. Wearing cotton gloves, the young woman leaned into the crate, removing layers of Ethafoam packing from around the mummy. Ringlets of black hair fell around her face. She straightened and shoved her hair back, revealing eyes as dark and striking as those painted on the mask. Her Mediterranean features could well have appeared on any Egyptian temple painting, but her clothes were thoroughly modern: skinny blue jeans and a Live Aid T-shirt.

“Beautiful, isn’t she?” murmured Dr. Robinson. He’d moved beside Maura, and for a moment she wondered if he was referring to Madam X or to the young woman. “She appears to be in excellent condition. I just hope the body inside is as well preserved as those wrappings.”

“How old do you think she is? Do you have an estimate?”

“We sent off a swatch of the outer wrapping for carbon fourteen analysis. It just about killed our budget to do it, but Josephine insisted. The results came back as second century BC .”

“That’s the Ptolemaic period, isn’t it?”

He responded with a pleased smile. “You know your Egyptian dynasties.”

“I was an anthropology major in college, but I’m afraid I don’t remember much beyond that and the Yanomamo tribe.”

“Still, I’m impressed.”

She stared at the wrapped body, marveling that what lay in that crate was more than two thousand years old. What a journey it had taken, across an ocean, across millennia, all to end up lying on a CT table in a Boston hospital, gawked at by the curious. “Are you going to leave her in the crate for the scan?” she asked.

“We want to handle her as little as possible. The crate won’t get in the way. We’ll still get a good look at what lies under that linen.”

“So you haven’t taken even a little peek?”

“You mean have I

unwrapped

part of her?” His mild eyes widened in horror. “God, no. Archaeologists would have done that a hundred years ago, maybe, and that’s exactly how they ended up damaging so many specimens. There are probably layers of resin under those outer wrappings, so you can’t just peel it all away. You might have to chip through it.

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher