![Rizzoli & Isles 8-Book Set]()

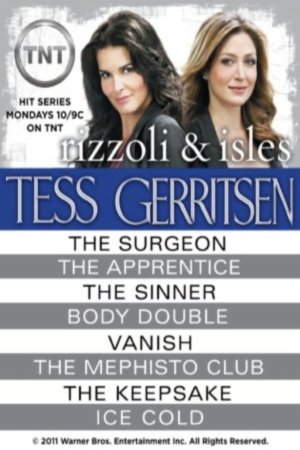

Rizzoli & Isles 8-Book Set

who chose to be outside in the heat. I crave the heat; it soothes my cracking skin. I seek it the way a reptile seeks a warm rock. And so, on that sweltering day, I drank coffee and considered the human chest, puzzling over how best to approach the beating treasure within.

The Aztec sacrificial ritual has been described as swift, with a minimum of torture, and this presents a dilemma. I know it is hard work to crack through the sternum and separate the breastbone, which protects the heart like a shield. Cardiac surgeons make a vertical incision down the center of the chest, and split the sternum in two with a saw. They have assistants who help them separate the bony halves, and they use a variety of sophisticated instruments to widen the field, every tool fashioned of gleaming stainless steel.

An Aztec priest, with only a flint knife, would have problems using such an approach. He would need to pound on the breastbone with a chisel to split it down the center, and there would be a great deal of struggling. A great deal of screaming.

No, the heart must be taken through a different approach.

A horizontal cut running between two ribs, along the side? This, too, has its problems. The human skeleton is a sturdy structure, and to spread two ribs apart, wide enough to insert a hand, requires strength and specialized tools. Would an approach from below make more sense? One swift slice down the belly would open the abdomen, and all the priest would have to do is slice through the diaphragm and reach up to grasp the heart. Ah, but this is a messy option, with intestines spilling out upon the altar. Nowhere in the Aztec carvings are sacrificial victims depicted with loops of bowel protruding.

Books are wonderful things; they can tell you anything, everything, even how to cut out a heart using a flint knife, with a minimum of fuss. I found my answer in a textbook with the title

Human Sacrifice and Warfare,

written by an academic (my, universities are interesting places these days!), a man named Sherwood Clarke, whom I would very much like to meet someday.

I think we could teach each other many things.

The Aztecs, Mr. Clarke says, used a transverse thoracotomy to cut out the heart. The wound slices across the front of the chest, starting between the second and third rib, on one side of the sternum, cutting across the breastbone to the opposite side. The bone is broken transversely, probably with a sharp blow and a chisel. The result is a gaping hole. The lungs, exposed to outside air, instantly collapse. The victim quickly loses consciousness. And while the heart continues to beat, the priest reaches into the chest and severs the arteries and veins. He grasps the organ, still pulsating, from its bloody cradle and lifts it to the sky.

And so it was described in Bernardino de Sahagan’s

Codex Florentio,

The General History of New Spain:

An offering priest carried the eagle cane,

Set it standing on the captive’s breast, there where the heart had been, stained it with blood, indeed submerged it in the blood.

Then he also raised the blood in dedication to the sun.

It was said: ‘Thus he giveth the sun to drink.’

And the captor thereupon took the blood of his captive

In a green bowl with a feathered rim.

The sacrificing priests poured it in for him there.

In it went the hollow cane, also feathered,

And then the captor departed to nourish the demons.

Nourishment for the demons.

How powerful is the meaning of blood.

I think this as I watch a thread of it being sucked into a needle-thin pipette. All around me are racks of test tubes, and the air hums with the sound of machines. The ancients considered blood a sacred substance, sustainer of life, food for monsters, and I share their fascination with it, even though I understand it is merely a biological fluid, a suspension of cells in plasma. The stuff with which I work every day.

The average seventy-kilogram human body possesses only five liters of blood. Of that, 45 percent is cells and the rest is plasma, a chemical soup made up of 95 percent water, the rest proteins and electrolytes and nutrients. Some would say that reducing it to its biological building blocks peels away its divine nature, but I do not agree. It is by looking at the building blocks themselves that you recognize its miraculous properties.

The machine beeps, a signal that the analysis is complete, and a report rolls out of the printer. I tear off the sheet and study the

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher