![Saving Elijah]()

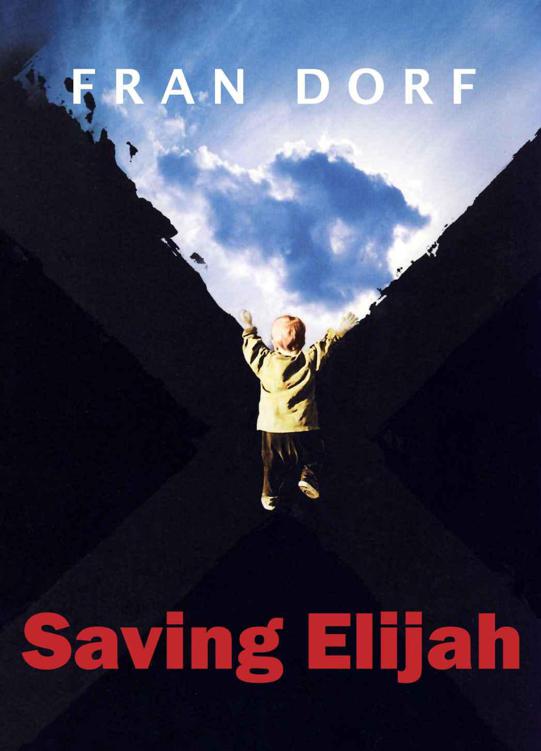

Saving Elijah

compassion. I had obviously chosen the wrong profession, I had never helped anyone.

"I need to get a history," the doctor said.

I bowed my head. "Psychologist." I looked up, half expecting him to be laughing.

He wasn't. "Dinah," he said, "I was wondering if you feel like you ever deserve to be happy again."

"If Elijah dies ..." I started to tear up. "I guess I can't even imagine ever being happy again."

"But he's well, you say. What makes you think he's going to die?"

I folded my hands on my lap. "It's as if I have the other outcome in my head, as if the demon put it there, as if I've already lived it. So that I know exactly what would have happened. They have to hook Elijah up to machines to keep him alive, and I cannot let him go, and I—we—go on and on and on that way, for years. My family is destroyed. I am destroyed."

"You feel you're destroyed now, according to what you've told me."

"Yes. I do. In a different way."

"What's different?"

"My son is alive."

"I see. In this other outcome, after you refuse to remove the machine, what happens then?"

I closed my eyes, and an image came into my mind, a pale face, lips stuck in a pursed position, bitterness and anger in the eyes.

"I become like my grandmother."

"What about her?"

"Bitter, hateful, terribly sad."

He made a few more notes, then looked up.

"Do you have any children?" I asked him. I wanted him to be human, to listen to me, to stop making the judgments I knew he was making. "Two."

"If you lost one, could you imagine ever being happy again?"

He sighed. "Dinah, have you ever treated complicated grief?"

The terms we call it seemed so stupid. Complicated grief—what did that mean, how did that describe the pain of losing a child?

"Yes. But it's just bullshit, everything I did, everything I said, was bullshit. Total bullshit."

He smiled. "Did you think that at the time?"

"No, but I didn't know what it was like, losing a child."

"Dinah, did these bereaved patients walk out your door better able to cope than when they came?"

I shrugged. I had no patients now, of course.

"Did they?"

"I suppose so."

"So then why do you now think that you didn't help them?"

I was crying. "Because I didn't understand."

"Did you have to understand to help? Isn't compassion mostly just a willingness to be close to suffering?" He watched me blow my nose.

I couldn't see it that way anymore. "It's not enough," I said, hiccuping, looking out the window, which had a view of the interstate, where construction and an accident had brought traffic to a dead stop. I'd been stuck in the jam myself on the way down.

"Let's go somewhere else," Kessler said. "Your son lived. Do you have to suffer for that, for happiness?"

"Look. I know what you're going for, you want to talk about my mother and my childhood and show how I've manufactured all this because Charlotte made me feel unworthy when I was a little girl. But even if this demon is composed of my ego deconstructed by grief, it's still real."

He grinned. "I guess I'm going to have to do better if I want to get anywhere with you, huh?"

I offered a smile. "Look, I worked on all that when I was studying for my doctorate and went into therapy myself. I even worked on the issue of my abusive relationship with Seth Lucien"

He stood up and walked over to his mahogany desk, leaned against it. "Maybe you need more work."

"Maybe so," I said. "But how can you say for sure that there aren't entities in this universe that feed on human suffering? Maybe they can even create themselves out of suffering."

He crossed one leg over the other. "I'm sorry, Dinah. I just don't have it in me to believe your story. I believe you're suffering. But you know as well as I do that I can't collude with your hallucinations."

"You'd have done the same thing if it'd been your son." He was trying, and he was as unhelpful as I had been with my own bereaved patients.

twenty-seven

Dinner. I had opened all the cabinets and the refrigerator several times before facing the fact that there was nothing in either that qualified as supper material. I'd given up my practice and my writing class and my column and my marriage and I still couldn't find the time to go shopping. Sam had been sending checks, so I still could go shopping, had I been able to organize myself to do it. Who knew how long Sam's sending checks would last, anyway? One day, any day, he might say he'd only continue to support me if the kids went to live with him. If he took me to

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher