![Saving Elijah]()

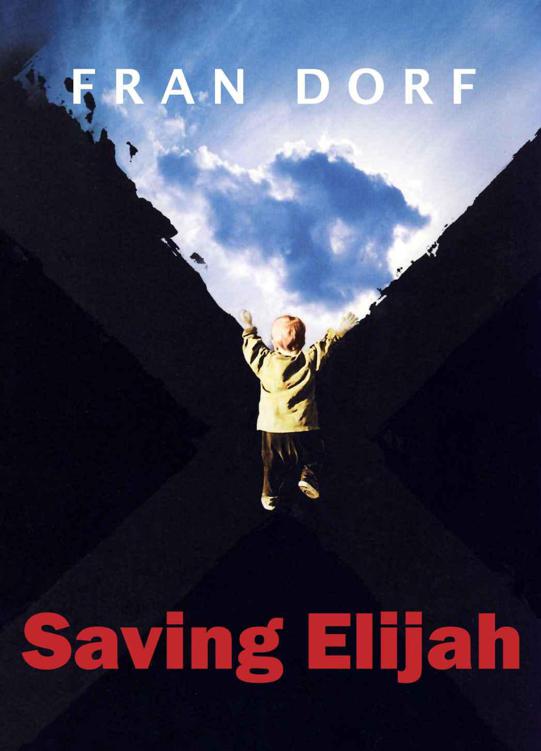

Saving Elijah

appearance, toward the end of breakfast the next day. We were eating formally, in the dining room on the gold-rimmed white china. The minute she came in I knew this was the woman who'd been standing by the camellia garden the night before. My grandmother was a tall and thin woman, with dull, gray hair she wore in a loose knot. Her dress had a large stain at the bosom and her mouth had these little ridges around it, as if she had pursed her lips and her face got stuck that way. Her eyes were deep-set, and so light they seemed almost clear. She held herself rigidly straight, as if she had a steel bar holding up her back, and stumbled a bit as she walked. Her arms and hands didn't seem to move with her when she moved, either, and anyway she moved as slowly as anyone could unless they were standing still. She didn't look solid somehow, even standing right there.

"Hello, Mother." Grandma Elizabeth bent down to kiss my mother but was left kissing air because my mother turned her cheek away. "And Martin. How nice to see you. So very nice." Her speech had a vapid, singsong cadence.

"Yes, Liz, it's nice to see you again."

Grandpa Eli asked Bernard to introduce me and Dan to our grandma. She bent down slowly, one inch at a time, and kissed me on the cheek. "And you must be Dinah. How nice to meet you."

I winced. Her breath was sour. "Nice to meet you, Grandma."

"You look like your mother did at your age."

Charlotte was watching us intently from her place at the other table. I knew it wasn't true. After all, I was Tubby Turd and my mother had been thin and perfect and beautiful. No. Wait. She was chubby when she was a girl, just like me.

Uncle Bernard drew Grandma Elizabeth on to my brother. Dan held out his hand.

"Oh." She seemed flustered but held out her own hand. I thought my brother's vigorous handshake would knock her over. She already looked like she might blow away.

She closed her eyes and when she opened them she suddenly gripped my brother's hand and held on tight, for the longest time. I thought she'd never let go, but then she let his hand drop and used hers to smooth his hair several times. Tears came to her eyes.

Finally she said, "I had a little boy once. His name was Charlie. You look just like Charlie." A smile flashed across her face.

"Elizabeth, shut up." Grandpa Eli's voice was even uglier than his words. His teeth were clenched and a vein stood out on his neck. "The boy does not look like Charlie."

"Of course he does, Eli." She glared at him. He glared right back. How could this be? Grandpa Eli had seemed almost jolly before. How could they live together in this house and look at each other with such hate? I often saw hair-trigger changes in my mother, but it seemed different with a mother and a kid. And maybe Grandma Elizabeth was right. Maybe Charlie, like my brother, had dark skin and hair that really stood out in this family with so many redheaded, light-skinned children.

"Go upstairs, Elizabeth," Grandpa Eli said. "Don't spoil it for everyone."

Grandma Elizabeth brought her index finger to her lips and said, "Shhhh. I'm not allowed to ever speak of the dead in this house. It's forbidden by the master." The way she said that word chilled me.

She sat down at the adult table, and everyone went back to eating. But when I happened to look again about ten minutes later she was gone. She only came down once again, on Christmas morning. Busy opening presents, including a beautiful locket from Grandpa Eli, I noticed that she kept sneaking looks at my brother, as if she were expecting him to get up and do something amazing.

"Stop it, Mother!" My mother must have noticed it, too. She was mad, I certainly knew her mad look.

Grandma Elizabeth just got up and shuffled and stumbled out of the room. I saw her only a few more times in my life, as the Christmas visit to Atlanta became a despised yearly event, one that was always strained and difficult for my mother (which meant it was horrible for me). The grandparents and cousins came north for Dan's Bar Mitzvah, but that was it. The last time I saw her, all of them, was at Grandpa Eli's funeral when I was fifteen. I didn't want to be there, standing at the grave, a light cool drizzle sprinkling on my arms under a gunmetal sky, as gray as my grandmother's hair.

I was thin and fidgety and jazzed up on black beauties, and it was obvious my cousins didn't want me in Atlanta any more than I wanted to be there. The rabbi was reciting the prayers, and I was

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher