![Saving Elijah]()

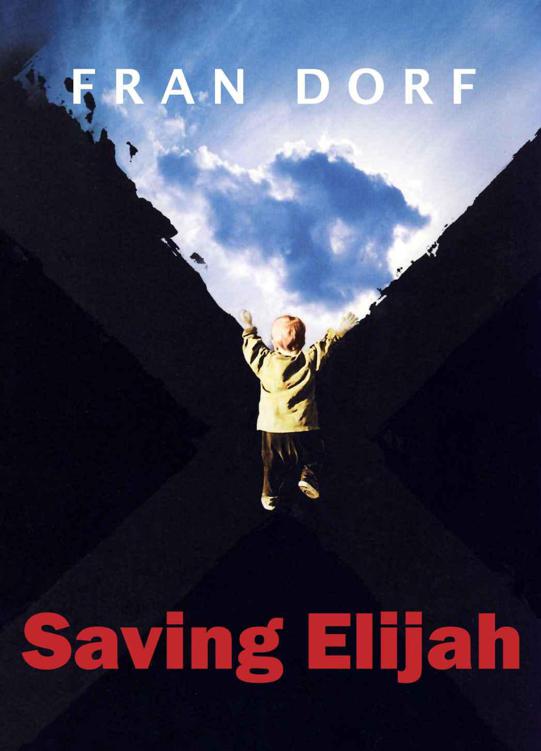

Saving Elijah

thinking that I hadn't even known my grandfather, though I would have liked to, and suddenly I noticed Grandma Elizabeth staring at my brother again. She was swaying—by then I understood that she was drunk—although no one seemed to notice it, or never said so if they did. My mother, on the other hand, often made embittered comments about her lush of a mother. I wondered how my grandmother could think my brother looked like her dead child.

He'd drowned when he was four, it had to have been more than fifty years ago, my brother was now twenty years old. What a weird old lady. So transfixed by her loony fantasies about my brother that she didn't even notice when the rabbi handed her the shovel to toss the dirt on the casket after it had been lowered into the ground.

That night I stood in the hallway of the big house in Atlanta and listened to private conversations.

"What is wrong with you, Mother?" Charlotte said. "My son's name is Daniel."

There were some exchanges too low for me to get, then I heard Grandma scream at the top of her lungs: "Go home, Charlotte! I don't want you here, I never want to see you again."

I felt nothing for my mother, for the pain she must have felt, being screamed at and summarily dismissed by my grandmother. I loathed my mother. I was jazzed.

My grandmother died the year I turned sixteen, and none of us went to her funeral.

ten

I did not see the ghost again until several days after Jimmy died. I tried to soothe myself by conjuring up the vision of my son as an eight-year-old, an Elijah who could express ideas and wonder about God, an Elijah who wasn't afraid of water. I attempted to recapture the image of the two of us on a boat in a great azure sea, but by the end of the second week that rapturous vision was getting fainter and smaller, no bigger than a distant point on the horizon. It was the others—the horrors—that now loomed huge.

I could understand my grandmother's melancholy now. She was pitiable because she was filled with relentless sorrow, and wretched because she was angry, and couldn't help herself. Her grief weighed hundreds of pounds and sat like a monster on her shoulders. She'd never been able to cast out the monster, or even tame it—it had poisoned her marriage and the rest of her life. I'd never thought about her compassionately, about the pain of losing a child, what it does to you. I'd treated grieving mothers, of course. Had I believed sitting with all the pain prepared me for feeling it?

I kept whispering in my son's ear: "Wake up, Elijah! You have to come back to your Mommy because there's so much more to live. You have to dance to Elvis. You have to look at me through your glasses, give me the best hugs. You have to learn to swim, to tie your shoes! You have to come back because I can't survive without you, I would miss you too much, the monster grief will sit on my shoulders and haunt me for the rest of my life."

If Life rejected me, hell, I would reject Life right back, surrender my own life to the sulking, hulking monster Big Time Grief, just like Grandma Elizabeth.

After I told Elijah all that, I stopped and waited and listened, but there was no sound from my son, no sign from God, not even a word from my ghost, nothing from anything except the whoosh-pumping machine. And time was running short. Even Moore seemed less convinced Elijah was going to wake up soon, though he never said so. He never said anything directly.

Just before the rest of the family arrived that evening, Uncle Lee showed up. My brother had yet to make an appearance. He'd called from Ohio and asked if I wanted him to fly in because he might be able to find something out from the doctors that I couldn't—he was, after all, one of them. I managed to say he could come if he wanted to, and not hang up on him. Uncle Lee had flown in all the way from San Francisco, still a slight man, now sixty-two, who still somehow looked boyish.

He hugged me for a long time, then bent down over Elijah and hugged him, whispered something in his ear while Sam and I watched. Elijah just lay there.

He stood up again. "George came, too, Dinah," he said.

I nodded. George and Lee had been together for twenty-five years.

"He's waiting outside, he didn't feel it was his place to come in. But he's praying, Dinah. He's praying for Elijah. And for you and Sam."

Lee put both hands on my shoulders, leaned in. "This story has a good ending, Dinah."

I remembered one we made up when I was about twelve

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher