![Saving Elijah]()

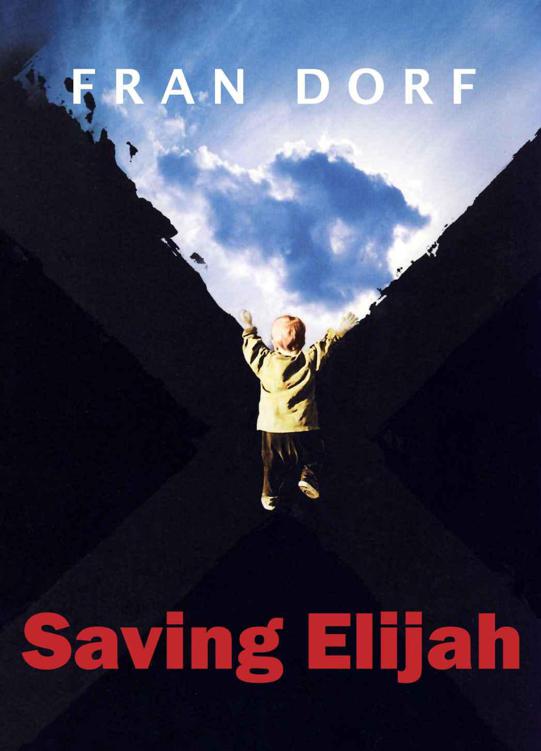

Saving Elijah

bigger now, taller at least, quiet and stiff, back arched, mouth open. His eyes are quivering in their sockets. I look at the respirator, watch the bulb inside the tube inflate, deflate.

Whoosh and pump. I want to take the loathsome machine apart, piece by piece, the bulb and the tube, every gear, crank, and computer chip, and smash them all, grind it all into dust.

I notice there's a second IV line. I hear a whistling sound from Elijah's chest.

Jane comes in. Elijah needs a dressing, he needs to be turned, he needs an adjustment of the feed, he needs. It takes so much effort to keep him alive.

She moves Tuddy to the bottom of the bed, places her palm with its tiny fingers on his forehead, smoothes back his hair, the silk that has now turned to straw, touches his other hand, holds it. His hands are now rigid, like claws. She listens to his lungs.

"What's this?" I point to the second line. My voice is altered. I sound like a machine when I speak, and I cannot speak louder than a whisper.

"He's got pneumonia again, Dinah. I can start him on another course of antibiotics, if you want me to."

With her tiny hands she keeps doing my bidding, saving him. "I guess I should call Sam." She stands aside while I go to the phone.

"Why are you asking me, Dinah?" Sam says. "You know what I think."

"I hate you, Sam." I hang up and turn to face Jane. "Give him the antibiotics."

I go back to him, sit down in the rocking chair, and watch while she sets up the new medicine. "It's amazing that you can come in here and grieve the way you do," she says.

Grieve? This is not grieving, this is atonement (for what I cannot even remember), this is hell, the living death. I have no more tears, I am sick to death of my tears, of my own skin. My eyes are as dry as bones. And Jane is just trying to be nice. No one can be nice to me. I hate them for being nice.

"Most of our parents don't ever come," she says.

"Why not?"

Jane sighs. "People deal with tragedies like this in different ways. For some people the only way they can deal with it is not to deal with it."

"What about the two in the corner? TJ and Louisa."

"I really can't talk about individual patients, Dinah," she says.

Right. At Easter there's always something of a crowd. Perhaps they expect resurrection. "Then why ... I mean, they just leave them here?"

"Some of our parents say their religion won't let them turn off the machines."

"Is it up to the parents?"

She sighs. "Who else?"

Who else, indeed?

"I can tell you this, Dinah," Jane says. "I have not seen Elijah make any responses that are purposeful. His brain stem is functional, barely, and that's about all. My opinion is he's vegetative. We can keep him alive, for some period of time, I don't know how much longer, but he will never recover, never be any different than he is right now."

I cannot even look at him anymore. She has not said this so directly before.

"I'm sorry," she says. "Would you like another doctor's opinion?"

* * *

The vision moves forward: Now I am in my own bedroom, getting ready for bed. Sam, naked, is pulling on his pajama bottoms. We have not made love in years.

"I went to see Father Tamari this morning," I say. I'd sat with him on a pew in front of a huge gory crucifix; he gave me a booklet about the five stages of grief.

"What for?"

"I just wanted to see what the Catholic Church would say. Don't you even want to know? You were raised in it."

Sam picks up the glass of scotch he's been nursing from the night table, and shakes the glass so that the ice tinkles. Tinkle Tinkle. Oh. Those chimes.

"So what did he say?"

"I talked to him for an hour or so. He was very nice, very sympathetic."

Sam takes another gulp. "Big deal."

"He said the Church believes in the sanctity of life."

He looks at me. "Yeah, this is real sanctified, Dinah. You suddenly planning to become a priest? Look. Dr. Angus said it. We are not pioneers here."

Wrong. I feel like a woman who's set out in a covered wagon with her young husband, looking for a place to call her own, bearing her children along the way, and burying them along the way, too. That woman would not have had to make this choice. Her choice would have been already made.

"I know."

Sam moves to wrap his arms around me. I cannot bear it and I duck so that he is left reaching for air.

"Dinah, we have to do this," he says. "You went to see Rabbi Leiberman last week. He supported it."

Temple Beth Elohim. The rabbi's office so cozy and lined

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher