![Saving Elijah]()

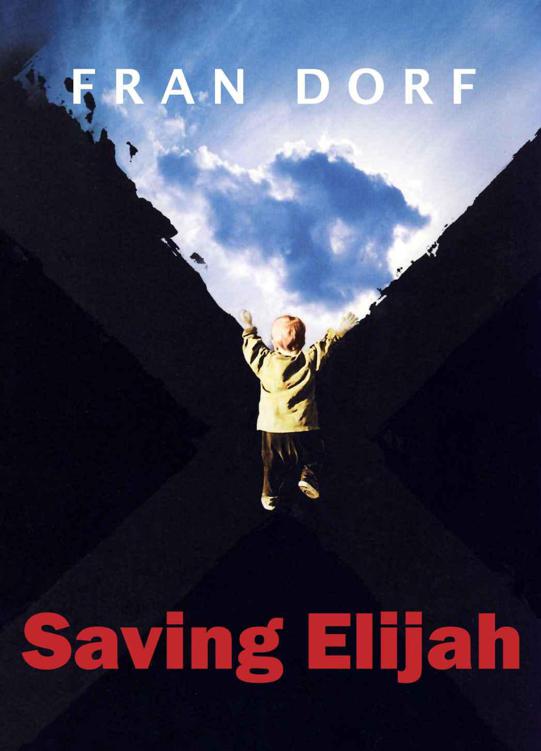

Saving Elijah

brother," she said. "And my first husband, and my daughter. My baby. "

When I opened my eyes I expected to see tears in her eyes. But Ellen Shoenfeld's eyes were clear and dry. I put my hand on her shoulder. "Why don't you try the regrets assignment?"

She waved me away and took her pocketbook on her arm. "Nein. Nein. Nein. "

* * *

That night, still safe in my complacency, in the comfort of my quotidian days, I dream I am on the motorcycle with Seth, my arms around his waist, my legs encircling his thighs, the leather of his jacket cool against my cheek.

He bears down harder and harder on the accelerator.

"This isn't real," I tell myself. I can't die because I'm not here.

But he is going faster, still faster. The wind lashes at my face. I see a truck in the distance. The road is too narrow, winding. Wait. No. Stop. This is his death, not mine.

I hear the sickening, screeching skid. I am soaring soundless through the cool air.

I search for Seth in the failing light. He is lying flat on his back a few feet away, face turned toward the sky, eyes closed. His jacket is covered with bits of leaves, his boots full of mud.

"Seth?" I struggle to all fours and crawl toward him.

He lifts his head and smiles. "Fooled you, didn't I?"

* * *

I awakened with a jolt and looked over at Sam, sleeping peacefully, snoring slightly. Breathing, breathing, I took inventory of my bedroom in the dark. The clock (2:30 a.m.), the novel I'd just begun on my night table, bottle of moisturizing lotion to cure alligator skin, the hulking furniture shadows—two overstuffed plaid chairs we got on sale at Ethan Allen, television set on its stand, armoire, dresser. Dog curled up in his usual place in the corner.

I told myself it had only been a dream. Like all dreams, it had been constructed of bits of my psyche, pieces of wishes and fears and guilt and life— my life.

It was just a dream, I told myself, and I even tried to believe it.

twenty

The next day I had a lunch date with Becky. I had decided to tell her the story of what had happened to me in my first year of college. Becky and I had confessed to each other practically everything else. Well, nearly everything. Maybe telling her would get it out of my mind, maybe she would reassure me that it wasn't my fault. Maybe I could then put it to rest. I had never even told Sam about Seth.

I couldn't bring it up because she brought someone along, as it turned out a delightful seventy-nine-year-old dowager whose house had provided her with her only sale of the year thus far. Mrs. Mitzi Hertzl had a sweet face with a tiny, perfectly painted rosebud mouth. She must have been very beautiful once, in a Lillian Gish sort of way.

"Buried two husbands, divorced two," she said as she took bird-sized bites of her ravioli. "Ready, willing, and able for number five."

I told her about my writing class and the four widowers in it, then invited her to join us.

"Sounds like fun," she said. "What are we working on?"

I told her.

"I know exactly what I'll write about. During the war, when I was in the WACs, I met the handsomest Englishman. I think he's what I regret."

"Why so?" Becky asked.

"He became my first lover."

We both leaned in.

"I wanted to marry him, but my mother, well, you know."

"Well," I said, "if that's what you regret, then that's what you should write about. I can't wait to read it."

On the way out of the restaurant, Mitzi Hertzl stopped, looked me up and down, following the line of my legs with her cane. "Good legs," she said. Meaning, if I ever found myself in need of a man, this news about my anatomy would come in handy. She was adorable.

* * *

When I got to the little conference room the following Thursday, Mitzi Hertzl was waiting for me just outside the door. I brought her in and introduced her to the class.

"Come sit by me," Abe said. "I'm Abe Modell." He patted the empty chair next to him. Abe always had a twinkle in his eye when he said anything to a woman.

Mitzi sat down next to him, smiling, then pulled out of her purse several pages torn from a legal pad and densely covered with writing. She unfolded the pages, smoothed them out, and squared them just so on the table in front of her.

"I'm glad you gave our regrets assignment a try," I said

"It's probably not very good."

"We're not into good or bad here," I told her. "We're into self-expression."

"WHAT?" Ellen Shoenfeld said.

"SELF-EXPRESSION."

She nodded, then smiled at

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher