![Secret Prey]()

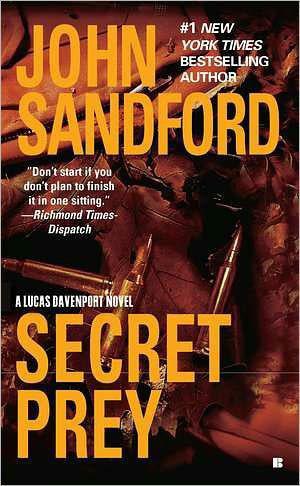

Secret Prey

picked up the sound of a car rolling to a stop outside the house, a subtle change from those few cars that simply tolled on by. In her dreams she thought, Lucas? though when awake she’d never remember the thought. But she was there, just rising to the cusp of consciousness, when the front window blew out.

SKEEEEEEEEEEEE.

The explosion shook her out of bed: she was up in an instant, not quite awake, but on her feet and moving; and as she moved, the smoke alarm in the living room went SKEEEEEEE.

She lurched into the hallway toward the living room; she was first aware of the light, then the heat, then the realization that she was staring into a fireball.

‘‘No! No!’’

And all the time: SKEEEEEEEEEE.

Weather moaned, registered her own moan as though she were standing out-of-body, then ran back down the hall to the bedroom, snatched up the bedside telephone and punched in 911. She got an immediate answer, and said, ‘‘My house just blew up. It’s burning, I’m at . . .’’ And she dictated the address and said, ‘‘I’ve got to get out.’’

‘‘Get outside immediately,’’ the cool voice said. ‘‘Just drop the phone and—’’

And the kitchen smoke alarm triggered, a slightly lower, less energetic note than the first, but just as loud: SKAAAAAAAAAAA.

She’d dropped the phone, almost stumbled over a pair of loafers on the dark floor, slipped them on, hit a light switch, was rewarded with lights. She padded back down the hall. The fireball seemed to have receded, or to have pulled back within itself: the flames were confined to the front room, to an area not much longer than her couch. There wasn’t yet much smoke, although the fire was roaring ferociously.

Weather moved in three quick steps to the kitchen, pulled a fat semiprofessional fire extinguisher from under the sink, pulled the pin as she walked back to the living room, aimed the nozzle at the flames, and squeezed the trigger. Whatever kinds of chemical were in the extinguisher blew out in a fog, and the fire seemed to cave in, but just for a second, and then it was back: no matter how much of the chemical estinguisher she poured on, the fire would only retreat and spring up on another perimeter.

SKEEEEEEE, SKAAAAAAAA . . .

She stepped closer, working the chemical, felt it slackening in force. To her right, she felt the photo of her parents and grandparents staring down from the walls, black-andwhite and hand-tinted photos she’d grown up with, memories she’d imported from her former home in the North Woods. With the extinguisher chemical almost gone, she tossed the container behind her, turned to the wall, and started pulling down the photos. Behind her, the fire burned with new authority, and she could feel the heat on her back and legs. She ran with the photos to the kitchen, fought her way back into the living room, tore open the low buffet, and took out a half-dozen photo albums and a box of photos she’d always meant to put in more albums.

And that was all she could do. The fire was growing quickly now, and she ran through the kitchen, well out onto the back lawn, dropped the albums, ran back inside—the smoke was heavy now, and she coughed, staggered—found the framed photos, and carried them through the smoke out back.

SKEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEEE, AAAAAAAAA.

She could hear sirens: the nearest fire station was no more than three quarters of a mile away. She started back inside one last time, unaware that she was panting, that her hair was frizzing and uncurling with the heat, that she’d taken spark burns on her hands and arms, that she’d walked on broken glass and cut her feet. She felt it all as discomfort, but she wanted to save the last things, some dishes her mother gave her . . .

She couldn’t reach them. The rug in the living room had ignited, and thick gray smoke was rolling through the house. She staggered back through the door just as the first of the fire engines arrived. She ran around the house as the firemen hopped off the truck, and yelled, ‘‘The front room . . .’’

THE NOISE NEVER STOPPED: SKEEEEEEEEEE, SKAAAAAAAAA.

Weather sat on the curb and watched the fireman knock down the front door.

And after a minute, she began to cry.

TEN

TEN O’CLOCK IN THE MORNING WAS AN EARLY HOUR for a man to be recalcitrant, Lucas thought, especially if he wasn’t a cop, but Stephen Jones was recalcitrant.

‘‘Of course I’d like to help, but I have the damnedest feeling that if I talk to you,

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher