![Shadows of the Workhouse]()

Shadows of the Workhouse

glistened in the corners of his eyes, and he murmured, “Perhaps it was best, all for the best. The Lord giveth, and the Lord taketh away.” He fell completely silent, lost in thought.

I had heard of two sons being killed in France, and looked at the picture of two handsome little boys on the wall. I asked, “Did you have any more children?”

“Yes, we had a little girl, and Sally nearly died in childbirth. I don’t know what went wrong, and the midwife didn’t know either, but my Sal was near to death for weeks after the birth. Her sister took the baby and wet-nursed her for the first three months, and the boys went to my mother. It frightened the life out of me, so I never let her go through it again. That’s one thing you learn about in the army, if nothing else: contraception. I never could understand these men who let their wives have ten or fifteen children, when they could prevent it.

“But Sally recovered, thank God, and the children came home. We called the little girl Shirley – don’t you think that’s a pretty name? She was the loveliest little thing in all the world and a blessing to us both.”

I did not need to see Mr Collet professionally more than once a week, because his legs were nearly better, but our sherry evenings continued, and during one of them he told me the story of Pete and Jack.

Young girls are not usually interested in war and military tactics, but I was. Wartime had shaped my childhood, but really, I knew little about war itself. The First World War was a mystery to me, and we were taught nothing about it in our history lessons at school. I knew that vast numbers of soldiers had died in the trenches of France, but so great was my ignorance that I did not even know what “trenches” meant. Later I met people who had suffered in the Blitz, and heard their first-hand stories, so when Mr Collett mentioned his sons’ experiences I encouraged him to talk.

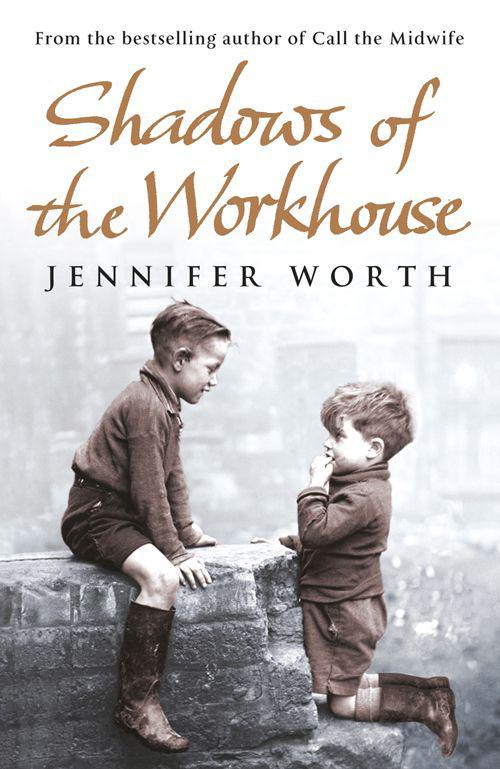

Pete and Jack had been sixteen years old when the war started. They had left school at the age of fourteen, and for two years had been Post Office telegraph boys, racing around London on their bikes delivering telegrams. They were known as “the flying twins”. They loved it, were proud of their work, proud of the uniform, and were both healthy from all the fresh air and exercise. But in 1914 war started, and a national recruitment campaign was launched. “It will all be over by Christmas” was the government’s promise. Many of their friends joined up, lured by the thought of adventure, and the twins wanted to go too, but their father restrained the boys, saying that war was not all adventure and glory.

1915 saw the launch of the famous poster of Lord Kitchener, pointing darkly out of the frame and saying “Your country needs you”. After that, young men who did not join up were made to feel that they were cowards. Hundreds of thousands of young men volunteered, Pete and Jack among them, and marched off to their graves.

The men were sent for three months’ military training in how to handle a gun and a grenade. Also how to care for horses and sword fighting for hand-to-hand combat were part of their training. Mr Collett commented wryly: “That just shows you how little the military High Command knew about mechanised warfare with high explosives!”

Men, boys and horses were packed into a steamer that stank of human sweat and horse droppings, and were shipped across the Channel to France. They were sent straight to the front-line trenches.

I said, “I’ve heard about this, front lines and trenches and going over the top and the likes, but what does it all mean?”

He said, “Well I wasn’t there – I was too old. I suppose I could have gone as a veteran, but the Post Office was vital work, because all communications were handled by the Post Office, so I don’t think I would have been released. However, I have met several men who were there at the front and who survived, and they told me the realities we never heard about back home.’

“Tell me about them, will you?”

“If you really want me to I will. But are you sure you want to hear? It’s not the sort of thing one should discuss with a young lady.”

I assured him I really did want to hear.

“Then you had better get me another drink. No, not that sherry stuff. If you look in the bottom of that cupboard you will find half a bottle of brandy.”

I filled his glass, and he took a gulp.

“That’s better. It upsets me, talking about it.

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher