![Sidney Chambers and The Shadow of Death (The Grantchester Mysteries)]()

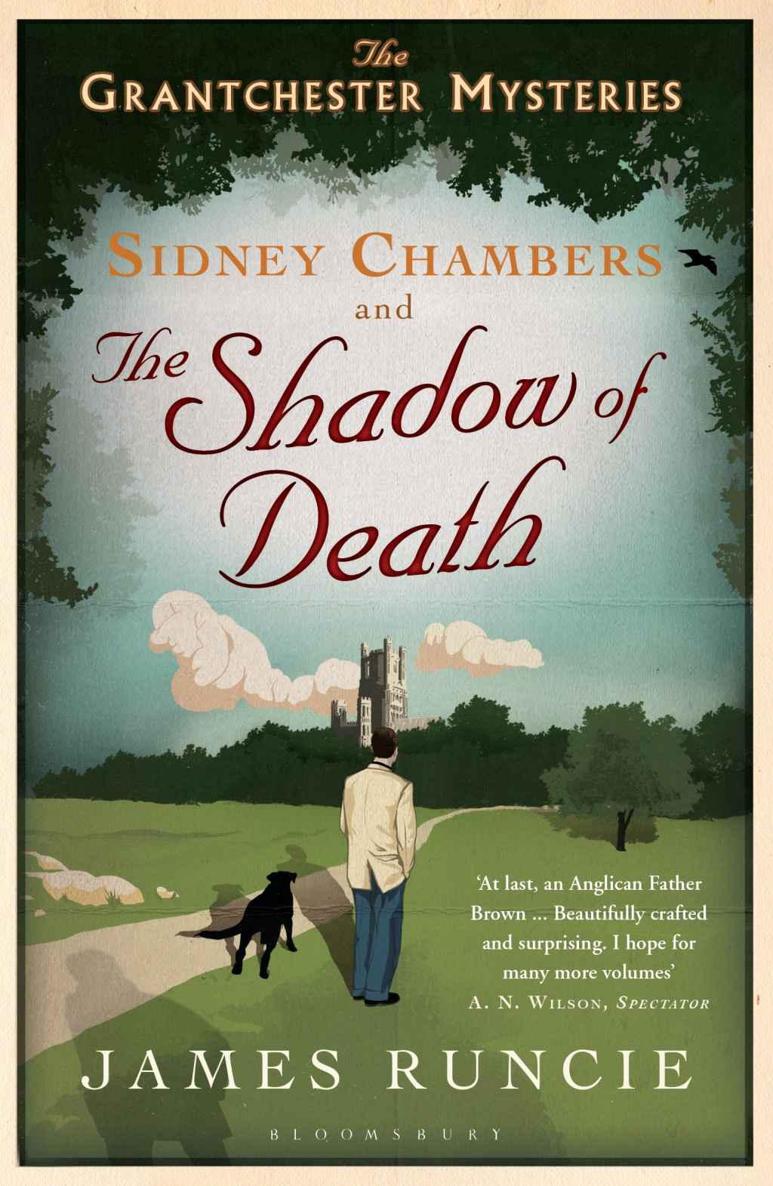

Sidney Chambers and The Shadow of Death (The Grantchester Mysteries)

speed. You can’t anticipate or measure these things. Nor do I think it at all reasonable for a doctor to come under suspicion every time one of his patients dies. Society has to trust the fact that he knows what is best for his patients.’

‘The fact?’

‘Yes, Canon Chambers, the fact; otherwise what is the point of a medical training? I make informed decisions about medicine. I have relatively uninformed opinions about theology and the current state of Her Majesty’s Police Force. These matters I leave to you and your friend the inspector. I put my trust in you. I do not interfere in your world and I expect you not to interfere in mine.’

‘But when people die our worlds collide.’

Dr Robinson leaned back in his chair, let out a long sigh and looked up at the ceiling. Then he spoke once more. ‘I don’t know if you have seen, Canon Chambers, at first hand, how debilitating a long illness can be; how bleak it is for a patient and how exhausting it is for those who have a duty of care?’

‘I have limited experience in this area, I admit; although I do know what it is like when people want nothing more than to die.’

‘In the war, I suppose.’

‘Yes. It was in the war.’

‘So you know how difficult the decision can be? Some pain cannot be eased. Sometimes there is no hope.’

‘Yes, and there are times when a decision has to be made very quickly.’

Dr Robinson paused before replying. ‘I see you understand the dilemma.’

He was waiting for more. Sidney then found himself telling a story. ‘I was in Italy in 1944,’ he began. ‘It was after the advance on Monte Cassino. We were in the Mignano Gap and had been under heavy mortar fire for three days. We went up the hill, sometimes crawling through the mud, and we faced a machine-gun attack that halved our number. I think I remember the noise more than anything else: the rounds of gunfire, the shouted orders, the cries of the wounded and the dying. Soldiers, my friends, so many of my friends, were howling for their mothers and their sweethearts. Howling. Then, even when we had pulled some of them to relative safety, their pain became unbearable. My commanding officer gave me a loaded revolver and said simply, ‘Do what you have to do.’

‘There was a boy of nineteen; red hair and freckles, and he had lost half his face. He would never be able to put his lips together again. There was no hope. His only sensation was unbearable pain. I stopped the pain. And I’ve never forgotten it. I remember it every day and I pray for him. I ask for God’s mercy.’

Dr Robinson sat quietly and thought about Sidney’s experience in silence. At last, he spoke. ‘I think I can guess why you have been telling me this, Canon Chambers. But I have done nothing wrong. My conscience is clear.’

‘I did not intend to tell you. I only came to meet you, and perhaps to advise you to be careful. Sometimes, I think, we are not always aware of how much we have to live with what we have done in the past. We can’t predict how these things will affect us.’

‘I am always careful, Canon Chambers.’

‘I would be very concerned,’ Sidney continued sternly, ‘if you did anything that might endanger your future, or that of Miss Livingstone, or indeed,’ and here he took a wild gamble, ‘that of your child.’

‘My child? What on earth are you talking about?’

‘I think you know perfectly well, Dr Robinson. I would hate to think that somebody so certain of their actions might leave a wife without a husband and a child without a father. Good day to you.’

Sidney was exhausted. He had not undertaken Holy Orders so that he could consort with policemen and threaten doctors. He had been called to be a messenger, watchman and steward of the Lord. He had a bounden duty to exercise care and diligence in bringing those in his charge to the faith and knowledge of God. And he had made a solemn promise at his ordination that there be no place left in him for error in religion or for viciousness in life. Yet, at this particular moment in time, everything was conspiring against him.

One of the problems of being a vicar, Sidney decided, was that you were always available. Just when you had settled down to writing the parish newsletter there would be a knock at the door or a ring of the telephone with news that could be urgent or trivial. It did not seem to matter which. All that mattered was that his attention was immediately required.

The morning after

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher