![Sidney Chambers and The Shadow of Death (The Grantchester Mysteries)]()

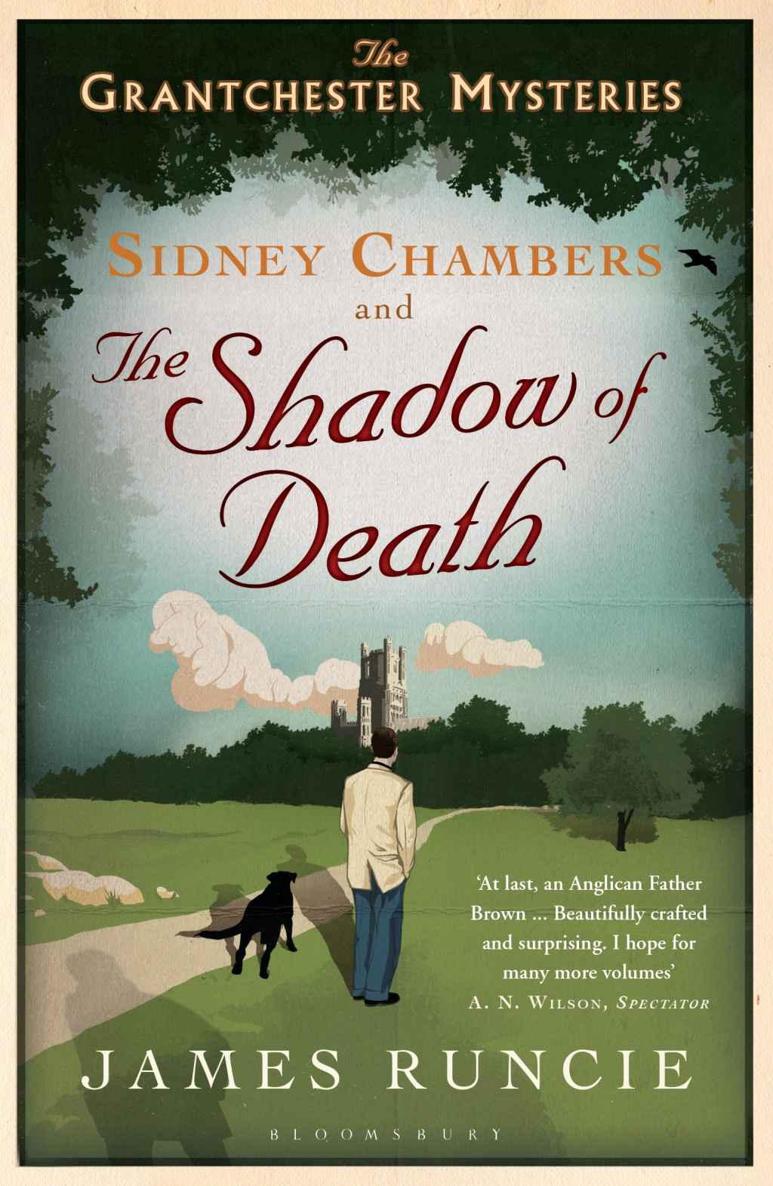

Sidney Chambers and The Shadow of Death (The Grantchester Mysteries)

The Shadow of Death

Canon Sidney Chambers had never intended to become a detective. Indeed, it came about quite by chance, after a funeral, when a handsome woman of indeterminate age voiced her suspicion that the recent death of a Cambridge solicitor was not suicide, as had been widely reported, but murder.

It was a weekday morning in October 1953 and the pale rays of a low autumn sun were falling over the village of Grantchester. The mourners, who had attended the funeral of Stephen Staunton, shielded their eyes against the light as they made their way to the wake in The Red Lion. They were friends, colleagues and relatives from his childhood home in Northern Ireland, walking in silence. The first autumn leaves flickered as they fell from the elms. The day was too beautiful for a funeral.

Sidney had changed into his suit and dog collar and was about to join his congregation when he noticed an elegant lady waiting in the shadows of the church porch. Her high heels made her unusually tall, and she wore a calf-length black dress, a fox fur stole and a toque with a spotted veil. Sidney had noticed her during the service for the simple reason that she had been the most stylish person present.

‘I don’t think we’ve met?’ he asked.

The lady held out a gloved hand. ‘I’m Pamela Morton. Stephen Staunton worked with my husband.’

‘It’s been a sad time,’ Sidney responded.

The lady was keen to get the formalities out of the way. ‘Is there somewhere we can talk?’

Sidney had recently been to see the film Young Man with a Horn and noticed that Mrs Morton’s voice had all the sultriness of Lauren Bacall’s. ‘Won’t you be expected at the reception?’ he asked. ‘What about your husband?’

‘I told him I wanted a cigarette.’

Sidney hesitated. ‘I have to look in myself, of course . . .’

‘It won’t take long.’

‘Then we can go to the vicarage. I don’t think people will miss me quite yet.’

Sidney was a tall, slender man in his early thirties. A lover of warm beer and hot jazz, a keen cricketer and an avid reader, he was known for his understated clerical elegance. His high forehead, aquiline nose and longish chin were softened by nut-brown eyes and a gentle smile, one that suggested he was always prepared to think the best of people. He had had the priestly good fortune to be born on a Sabbath day and was ordained soon after the war. After a brief curacy in Coventry, and a short spell as domestic chaplain to the Bishop of Ely, he had been appointed vicar to the church of St Andrew and St Mary in 1952.

‘I suppose everyone asks you . . .’ Pamela Morton began, as she cast an appraising eye over the shabby doorway.

‘If I’d prefer to live in the Old Vicarage: the subject of Rupert Brooke’s poem? Yes, I’m afraid they do. But I’m quite content here. In fact the place is rather too large for a bachelor.’

‘You are not married?’

‘People have remarked that I am married to my job.’

‘I’m not sure what a canon is.’

‘It’s an honorary position, given to me by a cathedral in Africa. But it’s easier to think of me as a common or garden priest.’ Sidney stamped his shoes on the mat and opened the unlocked door. ‘The word “canon” just sounds a bit better. Please, do come in.’

He showed his guest into the small drawing room with its chintz sofas and antique engravings. Pamela Morton’s dark eyes swept the room. ‘I am sorry to detain you.’

‘That’s quite all right. I have noticed that no one knows what to say to a clergyman after a funeral.’

‘They can’t relax until you’ve gone,’ Pamela Morton replied. ‘They think they have to behave as if they are still in church.’

‘Perhaps I remind them too much of death?’ Sidney enquired.

‘No, I don’t think it’s that, Canon Chambers. Rather, I think you remind them of their manifold sins and wickedness.’

Pamela Morton gave a half-smile and tilted her head to one side so that a strand of raven hair fell across her left eye. Sidney recognised that he was in the presence of a dangerous woman in her mid-forties and that this gesture alone could have a devastating effect upon a man. He couldn’t imagine his interlocutor having many female friends.

Mrs Morton took off her gloves, her stole and her hat, laying them on the back of the sofa. When Sidney offered her a cup of tea she gave a slight shudder. ‘I am so sorry if this seems forward but might you have something

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher