![Strangers]()

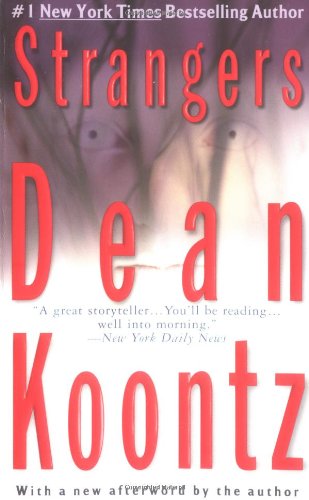

Strangers

unclamped the bottom of the Dacron graft, flushed it out, then tunneled the twin legs of it beneath the untouched flesh of the groin, beneath the inguineal creases, and into the incisions she had made in the femoral arteries. She stitched in both terminuses of the bifurcated graft, unclamped the restricted vascular network, and watched with delight as the pulse returned to the patched aorta. For twenty minutes, she searched for leaks and knitted them up with fine, strong thread. For another five minutes, she watched closely, in silence, as the graft throbbed like any normal, healthy arterial vessel, without any sign of chronic seepage.

At last she said, "Time to close up."

"Beautifully done," George said.

Ginger was glad she was wearing a surgical mask, for beneath it her face was stretched by a smile so broad that she must have looked like the proverbial grinning idiot.

She closed the incisions in the patient's legs. She took the intestines from the nurses, who were clearly exhausted and eager to relinquish the retractors. She replaced the guts in the body and gently ran them once again, searching for irregularities but finding none. The rest was easy: laying fat and muscle back in place, closing up, layer by layer, until the original incision was drawn shut with heavy black cord.

The anesthesiologist's nurse undraped Viola Fletcher's head.

The anesthesiologist untaped her eyes, turned off the anesthesia.

The circulating nurse cut Bach off in mid-passage.

Ginger looked at Mrs. Fletcher's face, pale now but not unusually drawn. The mask of the respirator was still on her face, but she was getting only an oxygen mixture.

The nurses backed away and skinned off their rubber gloves.

Viola Fletcher's eyelids fluttered, and she groaned.

"Mrs. Fletcher?" the anesthesiologist said loudly.

The patient did not respond.

"Viola?" Ginger said. "Can you hear me, Viola?"

The woman's eyes did not open, but though she was more asleep than awake, her lips moved, and in a fuzzy voice she said, "Yes, Doctor."

Ginger accepted congratulations from the team and left the room with George. As they stripped off their gloves, pulled off their masks, and removed their caps, she felt as if she were filled with helium, in danger of breaking loose of the bonds of gravity. But with each step toward the scrub sinks in the surgical hall, she became less buoyant. A tremendous exhaustion settled over her. Her neck and shoulders ached. Her back was sore. Her legs were stiff, and her feet were tired.

"My God," she said, "I'm pooped!"

"You should be," George said. "You started at seven-thirty, and it's past the lunch hour. An aortal graft is damned debilitating."

"You feel this way when you've done one?"

"Of course."

"But it hit me so suddenly. In there, I felt great. I felt I could go on for hours yet."

"In there," George said with evident affection and amusement, "you were godlike, dueling with death and winning, and no god ever grows weary. Godwork is too much fun to ever get weary of it."

At the sinks, they turned on the water, took off the surgical gowns they'd worn over their hospital greens, and broke open packets of soap.

As Ginger began to wash her hands, she leaned wearily against the sink and bent forward a bit, so she was looking straight down at the drain, at the water swirling around the stainless-steel basin, at the bubbles of soap whirling with the water, all of it funneling into the drain, around and around and down into the drain, around and down, down and down

This time, the irrational fear struck and overwhelmed her with even less warning than at Bernstein's Deli or in George's office last Wednesday. In an instant her attention had become entirely focused upon the drain. which appeared to throb and grow wider as if it were suddenly possessed of malignant life.

She dropped the soap and, with a bleat of terror, jumped back from the sink, collided with Agatha Tandy, cried out again. She vaguely heard George calling her name. But he was fading away in the manner of an image on a motion picture screen, retreating into a mist, as if he were part of a scene that was dissolving to a full-lens shot of steam or clouds or fog, and he no longer seemed real. Agatha Tandy and the hallway and the doors to the surgery were fading, too.

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher