![The Beginning of After]()

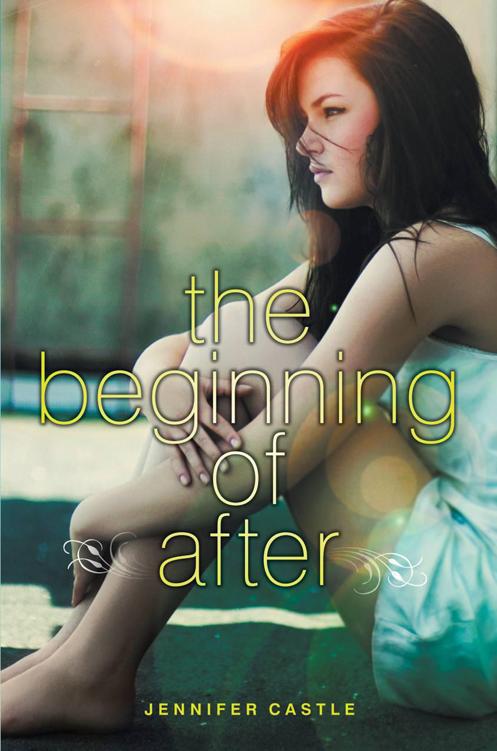

The Beginning of After

we spoke.

“You saw that a-hole?” asked Meg bitterly during one of our phone calls, when I finally got up the nerve to tell her that David had been here. “What did you say?”

I wasn’t sure what to share. It was as if by making some peace with him, I’d handed all my anger to my best friend for safekeeping. Meg knew every thought I’d ever had about every boy we knew, but how could she understand my concern for David when it perplexed me too?

“It was very businesslike,” I said. “Believe me, I was in no mood to see him.”

The receipt with David’s email address was still sitting in front of the computer. After a few days, I found myself drafting a message to him in my head.

Hi, David. How is Masher? Just wanted to see how he’s doing.

Hi, David! How are you and Masher? Hope you are both doing good.

Hi, David and Masher. Everyone okay?

No matter how many versions I wrote, I couldn’t find the right balance between “casual/friendly/concerned” and just plain lame. But eventually, I had to get it out of my brain, so I sat down to type:

Dear Masher,

WOOF! I hope you and David are doing well. I just wanted to remind you about your appointment!

The next day, I got this response:

WOOF back. Feeling great and planning to be there.

I couldn’t bring myself to put the date on my calendar, as if writing it down would make it seem more important than it was.

WHAT REMINDS ME MOST OF THE PERSON I LOST IS . . .

“Their stuff is everywhere.”

Suzie and I usually started off each session by her showing me a Feeling Flash Card and spinning a conversation out of whatever answer I came up with. I was honest and serious with my replies now.

“Do you mean their belongings?” Suzie asked.

“Nana cleaned up most of the clutter, but some things she just left. Neither of us can touch them.”

I thought of the crossword puzzle my dad had been working on the morning of the accident. It often took him all week to do them, scratching in a few words every day. Nana had left this one, two-thirds finished, tucked between the salt and pepper on the kitchen table.

“Laurel, have you been able to go into their bedrooms?”

“No,” I said simply.

“I understand about not touching things. It’s too soon. Eventually, you and your grandmother might consider packing up the ‘stuff’ and giving some of it away. It’s very cathartic. But for now, one thing you might want to do is go into your parents’ room and stay aware of what reactions you have.”

For two days after that session, every time I walked down the upstairs hallway I eyed my parents’ door. All I could feel was dread and a little fear, which was ironic considering how it used to represent a special kind of haven for me.

On the third night I finally got up the courage to go in.

It was cleaner than usual, with the bed made, the dresser drawers shut tight. My mother was a chronic drawer-leaver-opener, which drove my dad crazy. The books on both nightstands were stacked neatly and the hamper was empty. At some point, Nana must have done the laundry and put away the clean clothes.

I sat on the big king-size bed with the wooden antique headboard my mom had taken from the house she’d grown up in, and I actually had to remind myself that my parents were not alive anymore. They were so here in this room.

Suddenly, I remembered one night when I was probably seven or eight years old. I’d had a nightmare and wandered into the room, then scrambled onto the bed, to find that spot between my parents that was always warm and safe and waiting for me if I got scared.

Not saying a word, my mother held back the covers for me to snuggle in.

“I had a scary dream about hot lava,” I’d said.

“I’m sorry, baby. I hate bad dreams.”

“Do you get afraid too?”

“All the time.”

“What do you get afraid of?”

I’d hoped she would say monsters, or falling off a bike, or her friends not inviting her to their birthday parties. But she was quiet for a few moments and then said, “I’m most afraid of losing you or Toby.”

Arrrgh , I’d thought. “That doesn’t count. What else are you afraid of?”

Mom was quiet again, a deeper, more intense quiet, then said, “You losing me .”

I was little, but I’d known where that came from. One of her friends from college had just died of breast cancer a month or so before, leaving behind two kids.

Now I lay facedown on the bed, sobbing for the woman who once slept here not knowing

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher