![The Breach - Ghost Country - Deep Sky]()

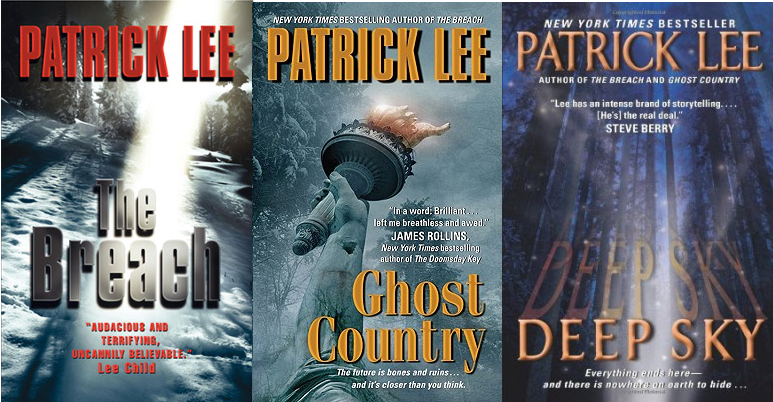

The Breach - Ghost Country - Deep Sky

panel below the stairs—and again only on the opposite side.

He became aware of Bethany’s breathing, off to his left. Intensifying and speeding up. Travis recalled her telling him once that she hated bugs. Deeply, irrationally hated them—a serious phobia she had no intention of coming to grips with. Now she stepped into his peripheral vision and pointed to a spot halfway between their position and the Breach. He followed. And saw.

One of the bugs was alive. It lay atop the detritus, fanning its wings in slow, delicate beats. It was visually similar to a hornet. Needle-thin waist, compound wing-structures, bristled thorax with some kind of stinger at the tip. Head to tail it was maybe six inches long.

Travis saw another just like it ten yards to the left—also alive. He picked out three more in the next few seconds.

Bethany steadied her breathing and spoke. “I thought they couldn’t come through.”

“They can’t, exactly,” Dyer said. “How they get here is tricky. That’s where the parasite signals come in. Bugs just like these ones transmit them from the other end of the tunnel. The way Garner described it, the signals can seek out conscious targets on this end. Living brains—the bigger the better. They get in your head and use it as a kind of relay, probably amplifying the signals, which are … kinetic. Telekinetic. They can trigger complex reactions in certain materials. Can rearrange them, at least on a tiny scale. Down at the level of molecules.”

“You mean the movement we felt inside our heads?” Paige said. She sounded more than a little rattled by the idea.

“No,” Dyer said. “Supposedly that feeling is just your nerves going crazy. The rearranging happens somewhere else—some random spot outside your body, but not far away.”

“What do you mean?” Travis said. “What do they rearrange?”

“Simple elements. Carbon, nitrogen, hydrogen, a few others. They assemble them to form a cell—basically an embryo. Like one of ours, but even smaller, and much less complex. The signals build it in about ten seconds, and then they cut out and the embryo is on its own, and the rest is straightforward biology.” He waved a hand at the mass of hard-shelled bodies beyond the glass. “Only takes the embryo a few weeks to develop into the full-sized form—probably a perfect copy of the transmitting parasite at the other end of the wormhole.”

Travis let the concept settle over him. He was struck not by how strange it was, but by how it paralleled much of what he’d read of biology in the past year. Propagation was life’s first objective. To spread. To be. It evolved stunningly elaborate ways of doing that, from the helicopter seeds of maple trees to the complex, two-stage life cycle of the Plasmodium parasite that carried malaria between mosquitoes and vertebrates—Travis had struggled to accept parts of that process as possible, even though it was hard science that’d been nailed down decades ago.

“Most of these things don’t live very long after they form,” Dyer said, “and a lot of the ones that do can barely move. It’s pretty clear they’re not built for this world. Wherever they’re from, maybe the gravity’s weaker and the air’s thicker. Who knows? But the thing is, some of them can move. And fly. Garner said there were serious injuries to the workers here in 1987. They set up these barricades as soon as they got a sense of what was happening, and pretty much by accident they figured out how to rein it all in.”

“Someone has to be a lightning rod,” Travis said.

Dyer nodded. “That’s close to how Garner described it. For whatever reason, if someone comes down here even a few times a day and makes a nice, easy target of himself, the signals never hunt any further. If they do have to look further, they eventually look much further, even through hundreds of feet of rock, somehow. And in that case they don’t stop at one target—they don’t seem to stop at all. The signals get stronger. The intervals between them get shorter. Peter Campbell and the others who were here at the beginning used equipment to work out the signal strength, and even some of the timing. There was some kind of reliable curve you could draw on a graph, showing how bad it would get if you left it untended too long. It would get out past Rum Lake after a while. It could extend for hundreds of miles.”

Travis stared over the tumble of insect debris and imagined Allen Raines’s

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher