![The Chemickal Marriage]()

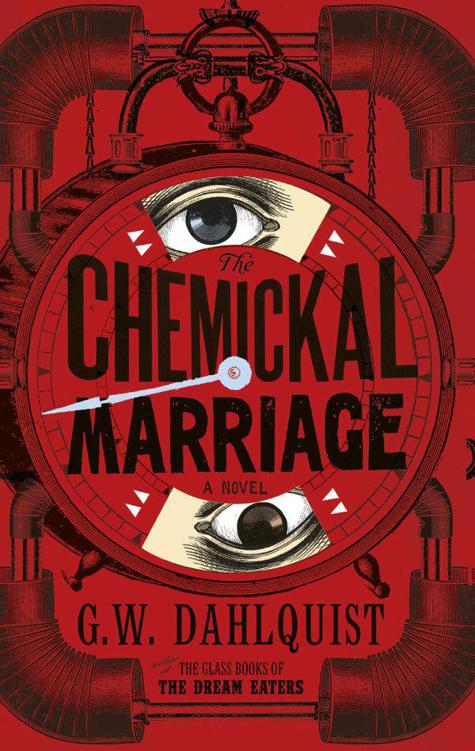

The Chemickal Marriage

resentment or his own sympathies. Chang stopped abruptly – sympathy and resentment, that was it exactly. Pfaff’s pride: he would seek a refuge where he felt

protected

, not anonymous. Chang had not wanted to show his face so soon, but there was one obvious place he could not avoid.

By the time he reached the Raton Marine, mist had risen and the tables outside had been abandoned. Chang pushed his way in and crossed to Nicholas, behind the bar. Both men ignored the sudden rustle of whispers.

‘I was told you were dead.’

‘An honest mistake.’ Chang nodded to the balcony and its rooms for hire. ‘Jack Pfaff.’

‘Is he not doing your business?’

‘The men he hired have been killed. Pfaff has probably joined them.’

‘The young woman –’

‘Misplaced her trust. She came here for help and found incompetence.’

Nicholas did not reply. Chang knew as well as anyone the degree to which the barman’s position rested on his ability to keep secrets, to take no favourites – that the existence of the Raton Marine depended on its being neutral ground.

Chang leant closer and spoke low. ‘If Jack Pfaff is dead, his secrets do not matter, but if he is alive, keeping his secrets will quite certainly kill him. He told you – I

know

he told you, Nicholas – not because he asked you to keep his trust, but because he wanted to brag, like an arrogant whelp.’

‘You underrate him.’

‘He can correct me any time he likes.’

Nicholas met Chang’s hard gaze, then reached under the bar and came up with a clear, shining disc the size of a gold piece. The glass had been stamped like a coin with an improbably young portrait of the Queen. On its other side was an elegant scrolling script: ‘Sullivar Glassworks, 87 Bankside’. Chang slid it back to the barman.

‘How many lives is that, Cardinal?’ drawled a voice from the balcony above him. ‘Or are you a corpse already?’

Chang ignored the spreading laughter and stepped into the street.

He broke into a jog, hurrying past the ships and the milling dockmen to a wide wooden rampway lined with artisans’ stalls. It sloped to the shingle and continued for a quarter of a mile before rising again. Once or twice a year the Bankside would be flooded by tides, but so precious was the land – able to deal directly with the water traffic (and without, it was understood, strict attention to such notions as tariffs) – that no one ever thought to relocate. Remade again and again, Bankside establishments were a weave of wooden shacks, as closely packed as swinging hammocks on the gun deck of a frigate.

The high gate – as a body Bankside merchants secured their borders against thievery – was not yet closed for the night. Chang nodded to the gatekeepers and strolled past. Number 87 was locked. Chang pressed his face to a gap near the gatepost – inside lay an open sandy yard, piled with barrels and bricks and sand. The windows of the shack beyond were dark.

His appearance alone would have caught the attention of the men at the gate, and Chang expected that they were watching him closely. He knew his key would not fit the lock. In a sudden movement Chang braced one foot on the lock and vaulted his body to the top of the fence and then over it. He landed in a crouch and bolted for the door – the guards at the gate would already be running.

The door was locked, but two kicks sheared it wide. Chang swore at the darkness and pulled off his glasses: a smithy – anvils and hammers, a trough and iron tongs – but no occupant. The next room had been fitted with a skylight to ventilate the heat and stink of molten glass. Long bars of hard, raw glass had been piled across a workbench, ready to be moulded into shape. The furnace bricks were cold.

No sign yet of the guards. Past the furnace was another open yard, chairs and a table cluttered with bottles and cups. In the mud beneath lay a scattering of half-smoked cigarettes, like the shell casings knocked from a revolver. The cigarette butts had been crimped by a holder. Behind another chair lay a ball of waxed paper. Chang pulled it apart to reveal a greasy stain in the centre. He put it to his nose and touched the paper with his tongue. Marzipan.

Across the yard lurked a larger kiln. Inside lay a cracked clay tablet: a mould, the indented shapes now empty, used with extreme heat to temper glass or metal. Each indentation had been for a different-shaped key.

From the front came voices and the rattling of the

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher