![The Chemickal Marriage]()

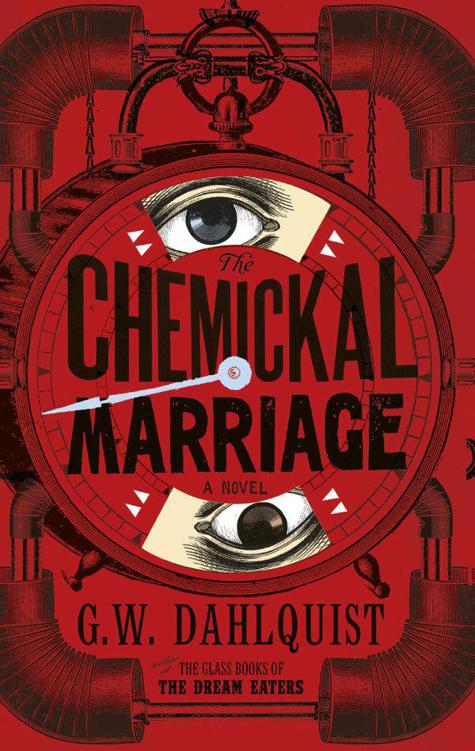

The Chemickal Marriage

its cold constraint.

He lit a candle and, scraping the crust from the sill, pushed the window shut. He quickly stripped off Foison’s clothing and laid out his own – redtrousers with a fine black stripe, a black shirt, a fresh black neckcloth and clean stockings. He stood for a moment, exposed to the waist, shaving mirror within reach, but then pulled the fresh shirt on, telling himself he’d neither the light nor time to examine the wound. Cunsher’s boots he kept, but availed himself of stockings, a handkerchief, gloves and a spare set of smoked dark glasses. The goggles had been a godsend, but he could not wear them and fight – too much of his vision was blocked off.

He knelt at his battered bureau, pulled the bottom drawer from its slot – a clatter of pocket watches, knives, foreign coins and tattered notebooks – and set it aside, pausing to pluck up an ebony-handled straight razor and drop it into his shirt pocket. He groped into the open hole, face and shoulder pressed to the chest-of-drawers. His fingers found a catch and an inset wooden box popped free: inside were three banknotes, rolled tight as cigarettes. He tucked them next to the razor, one at a time, as if he were loading a carbine, and turned his attention back to the box. Underneath the bank-notes was an iron key. Chang pocketed the key, dropped the empty box into its space and shoved the drawer back into the bureau.

He shrugged his way back into Foison’s black coat. It

was

warmer than it looked, and remained a trophy after all.

The Babylon lay on the edge of the theatre district proper, convenient to several notorious hotels – no surprise, given that its stock in trade lay less in strictly recognizable plays than in ‘historical’ pageantry, with the degree of accuracy proportionate to the lewdness of the costumes. The only offering he’d seen – whilst stalking a young viscount whose new title had prompted a naive rejection of past debts –

Shipwreck’d in the Bermudas

, featured sprites of wind and water, strapping seamen, and shapely natives clad in leaves that tended to scatter before the mischief of said sprites. Befitting an institution so shrewdly dedicated to fantasy, the Babylon permitted no crowd of admirers at its stage door – an alley where no money could be made. Instead, its performers escaped the theatre through a passage to the St Eustace Hotel next door, with both champagne and easy rooms in staggering distance, from all of which the owners of the Babylon exacted a share.

The rear door

had

attracted the attention of at least one man of secrecyand cunning. Cardinal Chang strode to it unobserved and opened the lock with his recovered skeleton key, determined to cut Pfaff’s throat at the slightest provocation.

It was too early for even the curtain-raising circus acts, but backstage would soon fill with stagehands (often sailors with their knowledge of ropes and comfort with heights) and performers, getting ready for their work. Chang found such entertainments dire. Was there not ample pretence in the world, enough mannered screeching – why should anyone crave

more

? No one in Chang’s acquaintance shared his disgust. He knew without discussing the matter that Doctor Svenson admired the theatre greatly – perhaps even the opera, not that the distinction mattered to Chang: the more seriously a thing was taken by its admirers, the more fatuous it undoubtedly was.

The man he pursued loved the theatre above all things. Chang found a wooden ladder, bolted to the wall, climbing in silence above painted flats and hanging velvet to a narrow catwalk. Jack Pfaff adored beauty but lacked the money to join the ogling fools in the St Eustace, settling to be a hungry ghost in the shadows. Past the catwalk was another lock, the opening of which must ruin any hope of surprise. Chang did not need surprise. He turned his key and entered Jack Pfaff’s garret.

Mr Pfaff was not home. Chang lit a candle by the sagging bed: peeling walls, empty brown bottles, a rotten, rat-chewn loaf, jars of potted meat and stewed fruits, once sealed with wax, knocked on their sides and gobbled clean, a pewter jug near the bed with an inch of cloudy water. Chang opened Pfaff’s wardrobe, an altar of devotion filled with bright trousers, ruffled cuffs, cross-stitched waistcoats and at least eight pairs of shoes, all cracked and worn, yet polished to a shine.

Pushed against the far wall, angled with the slant of the rooftop, was a desk

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher