![The Chemickal Marriage]()

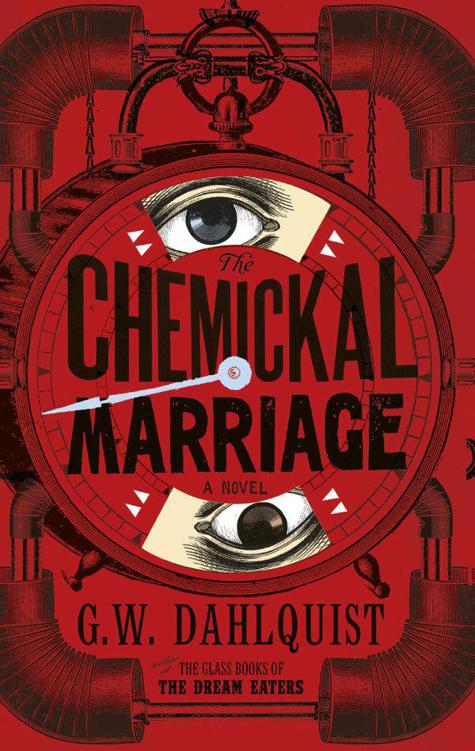

The Chemickal Marriage

Still the Contessa said nothing. Svenson sensed the span of her body between his fingers. He moved higher and squeezed again, feeling her ribs beneath the corset.

‘There is blood on your face,’ she murmured.

‘A way of dressing for the occasion.’

He released her and stepped away, pulling the revolver from his belt. The Contessa’s voice remained hushed.

‘For a moment I feared you might try to kill me … and then I understood that you have every intention of doing so. You have changed, Abelard Svenson.’

‘Is that so strange?’

‘When any man changes there ought to be fireworks.’

‘You still have every intention of killing

me

.’

The Contessa extended her left hand, the jewelled bag dangling, running her own fingers – pressing hard, her lips curling into a smile – the exact length of the scar from Tackham’s sabre.

‘I saw you, you know,’ she whispered, ‘bleeding on the ground, groaning like the damned … I saw you kill him. I thought you would die, just as I thought I had killed Chang. It is not often I underestimate

so

many people.’

‘Nor the same people so many times.’

The pressure on his scar was repulsive, but arousing. She lifted her fingers. ‘We overreach ourselves.’ Her cheeks held a touch of red. ‘Whatever your new

provocations

, there remains very much to do.’

At a pillared archway the Contessa raised her hand and they paused, peering into an ancient hall of high tapestries and cold stone walls. A row of tablesran down the centre of the room, arranged with bowls of floating white flowers.

Svenson craned his neck. ‘This room seems old – and, judging by the medieval decorations, quite out of fashion and unused.’

‘How do you account, then, for the flowers?’

‘A floral

penchant

of the Queen?’

The Contessa laughed. ‘No, because of the

drains

– the horrible drains! It is a wonder the entire royal household does not perish from disease. This chamber is particularly

fragrant

– but, while relining the pipes with copper would be an unthinkable expense, it is entirely acceptable to spend a colonel’s salary every fortnight on fresh flowers.’

‘Is this where the Privy Council meets, with Stäelmaere House under quarantine?’

The Contessa shook her head, enjoying her riddle. ‘Axewith took the Regent’s gatehouse. Because it boasts a

portcullis

– which tells you all you need to know about Lord Axewith. No, Doctor, there is no hope of getting anywhere near Oskar himself – he was always a coward, and he will have soldiers as thick around him as his old bearskin fur. I wonder if he’ll get another one? The real Vandaariff would never wear such a thing, but I don’t suppose anyone will care.’

‘Then where

have

you brought me?’

She pulled Svenson back into hiding. ‘We each have our talents, Doctor, and I have brought you where my own may shine. Observe.’

At the head of a cloud of men, all burdened with sheaves of paper, satchels, rolled documents, leather-bound ledgers, strode a thin young man with fair hair, the tips of his moustache waxed to a darker maple: Harcourt, the man they had collided with in the doorway. Svenson knew – from his days recuperating in Rawsbarthe’s attic – that Harcourt was an obsequious fellow whose advancement had come from never questioning his superiors’ commands, no matter how criminal. With so many riddled by sickness, Harcourt had vaulted to real power. Phelps had taken the news with dismay, but Svenson could see the burden did not weigh lightly on Harcourt’s shoulders. The young man’s face was haggard, and his voice – rapping out commands to thecrowd that clustered behind him like a burlesque of some multi-limbed Hindu deity – reduced to the flat crack of a toad.

‘The port master must receive these orders before the tide; requisitions to the mines must not be sent until

after

the morning’s trading; these judges called to chambers as soon as the warrants are approved;

local

militias marshalled for property seizure. Disbursements set against the Treasury’s reckoning as of

today

, we must draw down to demonstrate our need – Mr Harron, see to it!’

Harcourt swept on to the nest of tables. The Contessa pushed into Svenson as a determined portly figure – the dispatched Mr Harron, with a thick portfolio, each page dangling a ribbon weighted with a blot of wax – hurried by without stopping.

‘Will you drink something, Mr Harcourt?’ asked one aide, more concerned

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher