![The Chemickal Marriage]()

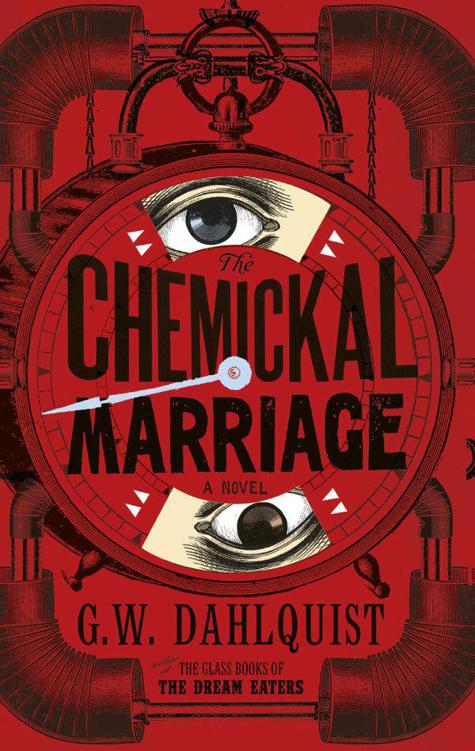

The Chemickal Marriage

for the canvas it held was immense.

Another cycle swept by, his attention lost in the details of swirling paint. The back of his mind throbbed with warning. Was this Harcourt’s card after all? But no, Harcourt’s transfixion had been erotic, and such was not, despite the extreme arousal of only moments before, his present experience. No … the emotion here was fear, controlled through great force of will, a deep-rooted dread emanating from the vision before his eyes, and in the sickening realization that far too much of the painting – and thus the intentions of its maker – remained incomprehensible.

This fear was especially strange coming from the body of the Contessa, for the memory came from her mind. However much the painting set the senses ablaze, he could not deny an anxious, thrilling tremor at feeling her body as his own – the weight of her limbs, the lower pivot of gravity, the grip of her corset …

The Contessa had learnt to make glass cards herself, from consulting her book. No doubt Harcourt’s card was also infused with some incident from her own life. Why had she sacrificed her own memories? Was her desperation so great as to warrant boring these holes into her own existence? Such questions the Doctor could only sketch in the backroom of his thoughts, as the greater part of his attention was devoured by the painted spectacle.

In form, the composition resembled a genealogical chart, centring around the joining of two massive families, each branching out from the wedded pair – parents, uncles, siblings, cousins, all punctuated by children and spouses. The figures stood without strict perspective, like a medieval illuminatedmanuscript, as if the painting were an archaic commemoration. Svenson felt his throat catch. A wedding.

This was the Comte’s canvas, mentioned in the

Herald

… what had it been called?

The Chemickal Marriage

…

That this was the work of Oskar Veilandt brought the canvas into clearer focus. The obsessively detailed background, which he had taken to be mere decoration, became a weave of letters, numbers and symbols – the alchemical formulae the Comte employed throughout his other work. The figures themselves were as vivid as Veilandt’s other paintings – cruelly rendered, faces twisted with need, hands groping for fervent satisfaction … but Svenson’s gaze could not long alight on any single figure without his head beginning to spin. He knew this was the Contessa’s experience, and that his path by definition followed hers.

Still, she had looked again and again, staring hard …

And then he knew: it was the paint; or, rather, that the Comte had inset slivers of blue glass within the paint; and sometimes more than slivers – whole tiles, like a mosaic, infused with vivid daubs of memory. The entire surface glittered with sensation, undulated like a heaving sea. The scope was astonishing. How many souls had been dredged to serve the artist’s purpose? Who could consume the lacerating whole and retain their sanity? His mind swarmed with alchemical correspondences – did each figure represent a chemical element? A heavenly body? Were they angels? Demons? He saw letters from the Hebrew alphabet, and cards from a gypsy fortune-teller. He saw anatomy – organs, bones, glands, vessels. Again the cycle played through. He felt the Contessa’s heroic determination to carve out this very record.

Eventually, Svenson was able to fix his gaze on the central couple, the ‘chemickal marriage’ itself. Both were innocent in appearance, but their voluptuous physicality betrayed a knowing hunger – there was no doubt of the union’s carnal aspect. The Bride wore a dress as thin as a veil, every detail of her body plain. One foot was bare and touched an azure pool (from which Svenson flinched, for it swam with memories), while her other wore an orange slipper with an Arab’s curled toe. One hand held a bouquet of glass flowers and the other, balanced on her open palm, a golden ring. Orange hair fell to her bare shoulders. The upper part of her face wore a half-mask uponwhich had been painted, without question, the exact features of the Contessa. The mouth below the mask smiled demurely, the teeth within bright blue.

The Groom wore an equally diaphanous robe – Svenson was reminded of the initiation garments of those undergoing the Process – his skin as jet black as the Bride’s was pale. One foot was buried in the earth up to the ankle, while the other was

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher