![The Land od the Rising Yen]()

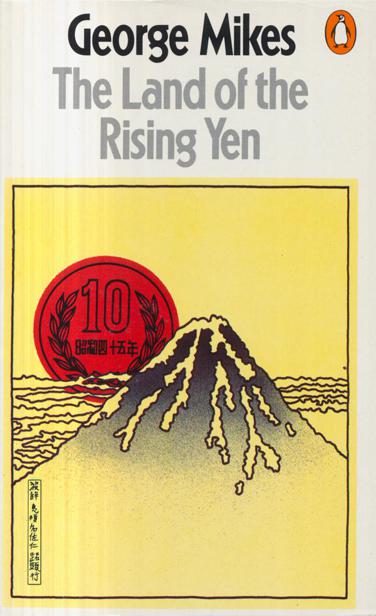

The Land od the Rising Yen

that the man who cleaned his study at the embassy was a treasure, a trusted

and much loved old employee, and, although a male, a paragon of all charwomanly

virtues. But he refused to clean the floor. Everything else, yes; the floor,

no. ‘He seems to think,’ his employer explained to me, ‘that if the gaijin is so stupid as to wear shoes inside his house, then he obviously does not want to have his floor clean.’

It is often said that the Japanese

are extremely clean at home, or inside any house or office, but dirty and

untidy outside. ‘Go and look at a railway station,’ I was told, ‘and you’ll be

horrified.’ I went and was horrified; horrified by the cleanliness of

the place. Although already shining white, it was being cleaned, washed,

brushed and scrubbed all the time. The floor was cleaner than many a restaurant

table I have come across in Europe.

The one great redeeming feature of

this disheartening cleanliness and tidiness is that it is always accompanied by

a sense of beauty. The Japanese have a strong aesthetic sense: they beautify,

embellish, adorn and decorate everything they touch. A sandwich in Japan is not just a sandwich, it is a work of art. It is cut into an artistic shape — it

can be circular, octagonal or star-shaped — and given a colour scheme with

carefully placed bits of tomato, coleslaw and pickles. There is, as a rule, a

flag or some other decoration hoisted on top. Every dish is aimed at the eye as

well as the palate. Every tiny parcel, from the humblest little shop, radiates

some original charm or at least tries to, and reflects pride: look how well done

it is! Every taxi-driver has a small vase in front of him, with a beautiful,

fresh, dark-red or snow-white flower in it. Once I watched a man at the counter

in a fish-restaurant. Sushi and sashimi — the famous raw fish of

Japan — comes in many forms and cuts, and it takes about ten years for a man to

reach the counters of a first-class establishment. The man I watched was not

bored with his somewhat monotonous job: he enjoyed every minute of it to the

full, took immense pride in it. Michaelangelo could not have set a freshly

carved Madonna before you with more pride and satisfaction than this cook felt

when he put a freshly carved piece of raw fish on your plate.

The Japanese are unable to touch

anything without beautifying it, shaping it into something pretty and pleasing

to the eye. One evening I was walking in one of the slummy suburbs of Tokyo and saw a heap of rubbish outside the backyard of a factory. It was an immense

mountain of rubbish, but it was not just thrown out as it came: all the boxes

were piled into a graceful if somewhat whimsical pyramid, while the loose

rubbish was placed on top as artistic and picturesque decoration. Someone must

have spent considerable time in converting that heap of rubbish almost into a

thing of beauty.

This universal striving for beauty

explains a great deal. I have said that psychoanalysis is gaining ground in Japan, but only slowly. Even so, it spreads more rapidly than neuroses. The Japanese take

pride in their work; they create — no matter what, but they create all

the time. They participate. Nothing is accepted just as it comes; nothing is

thrown at you. The phrase, ‘I couldn’t care less’ does not exist in Japanese;

they couldn’t care more. Every charwoman arrives early, leaves late and takes

pride in the beauty and comfort of the home she has to look after. If there is

something special afoot she will turn up on days when she is not supposed to

come and you have to think out polite and tricky ways of compensating her

because she will flatly refuse extra money and will be deeply hurt by your

offer.

A sandwich, then, is not just a

sandwich: it is a means of self-expression. A rubbish-heap is not just a

rubbish-heap: it is a modernistic, abstract sculpture which could be called

‘The Poetry of Urban Waste’. Tokyo is not only the largest city in the world;

not only the ugliest but also one of the most beautiful. The eruptive sense of

beauty of its people is overwhelming. Even in that huge conglomeration of men

and concrete this ubiquitous sense of beauty keeps a man a man, makes every

occupation — even the dullest — a job worth doing because it can be done a

little better. This sense of beauty makes life a satisfying experience, not

just a piece of drudgery performed by dreary robots. It turns every dustman

into an artist; makes every Japanese a creator.

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher