![The Land od the Rising Yen]()

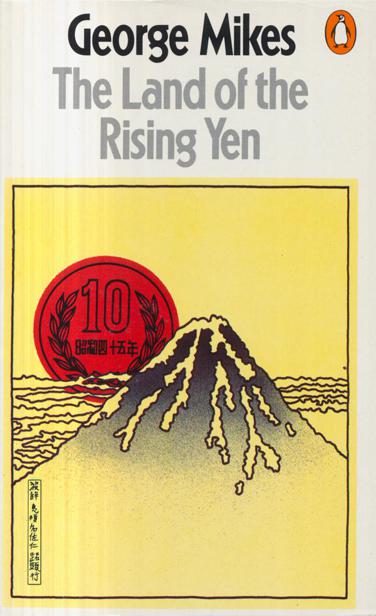

The Land od the Rising Yen

evening kimono while a Western couturier has to offer

something quite extraordinary for that price.

On the whole Japanese snobbery works

against traditional values and customs. Everyone is dressed (for work) in

Western suits and dresses; the young eat less rice and more potatoes: less fish

and more meat. Pizza is competing with raw fish and sake is giving

ground to whisky (£14 a bottle); cocktail-parties replace geisha-parties.

Hamburgers have come to stay and the hot dog reared its ugly head long ago.

You must also have a hobby. No matter

what, but a hobby — preferably with a new, Western touch. I taught a group of

elderly purveyors of frozen food tiddly-winks (completely unknown before) and

gained their everlasting gratitude. You must try to mix as many foreign words

in your Japanese as you can muster. And you must eat French bread. Long French

bread has a new but fast-spreading snob value; you see more of it than in France. And, of course, cheese. Cheese is a post-war discovery in Japan, the very word did not exist before, and they still call it cheesu. If you eat cheesu you are somebody; if you really love cheesu you have

arrived.

I fared pretty well in Japan. My social status was considerable. I have no Rolls-Royce; no electric potato-peeler.

But God, don’t I love cheesu.

LADIES AND GENTLEMEN

Man does not live by snobbery alone although

sometimes it looks as if he did. Britain’s influence does not consist solely of

Japanese adoration of Scotch whisky. Indeed, in a few cases British influence

can be mistaken for something it isn’t. Occasionally a pro-British attitude has

nothing to do with liking things British; it is simply one manifestation of a

slight anti-American trend. Generally speaking, British English is preferred in

Japan; not because it is nicer but because it is not American.

The Japanese character has strong

traditional traits but it is also a mosaic. The Japanese went out to learn, to

absorb, to imbibe foreign ways, methods, skills. So it is a legitimate question

to ask: how British are the Japanese? How American? How Chinese? How French?

HOW BRITISH?

They are very British, of course.

Quite a few similarities are obvious and have been dwelt upon many times. Japan is a small, overpopulated island east of Asia; Britain is a small overpopulated island west of

Europe. Both are parts of their respective continents in some ways, very

remote from them in many others. Japan’s application to join an Asian Common

Market could easily have been rejected. Both are the richest and most

industrialized nations of their regions. (Japan’s position has been confirmed

lately while Britain’s has become more dubious.) Both peoples reached out far

beyond their frontiers to rule other nations and occupy their lands. (While Britain’s empire may be dwindling, Japan’s was abolished at the stroke of a pen.) Both people have

extremely good manners and worship their ancestors, the British doing it more

subtly but no less devoutly than the Japanese. 11 Both nations have a long, close relationship with

the sea and both have got used to thinking in global terms. Both countries are

not just monarchies but devoted, almost religious, royalists. When King Farouk

of Egypt felt his throne wobbling in 1950, he remarked: ‘In half a century from

now there will be only five kings left in the world: the kings of Clubs,

Diamonds, Hearts and Spades, and the King of England.’ But Farouk made a

mistake: he forgot the Emperor of Japan. The Emperor of Japan was deprived of

his semi-divine status in 1945; the Queen of England has kept hers.

The British and the Japanese

character, too, have a great deal in common. Both are reserved and rather shy

people, ashamed of their feelings which are always covered up and carefully

hidden.

The Japanese ability to create muddle

rivals the British. The confusion the Japanese can cause with their refusal to

have proper postal addresses is phenomenal. Except in Kyoto and Sapporo (in Hokkaido) they have no street names. They name districts, buildings and

intersections (as if in London we had Selfridges and Oxford Circus, but no Oxford Street). They are quite sentimental about this refusal: that is their way, that is

their tradition, just as the British were moved to tears when they thought for

one horrible moment that they would have to give up Fahrenheit, easily the

worst system in the world, invented by an East Prussian. As a result more

postmen are in lunatic

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher