![The Mao Case]()

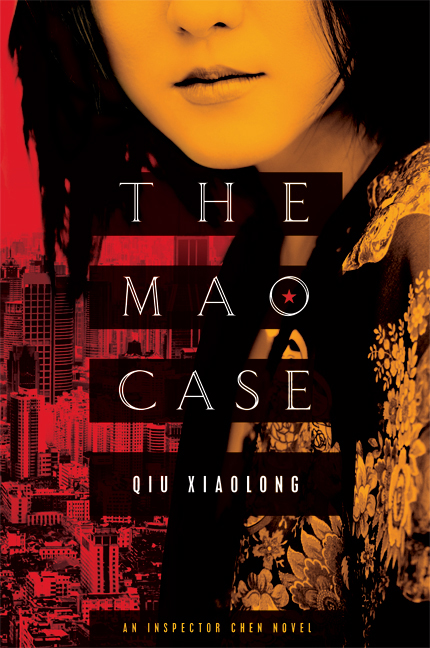

The Mao Case

knowledge he had learned

from those history books, some of which Chen was holding in his hands.

And Chen couldn’t help imagining Mao alone in the room, reading late into the night. According to the official publications,

Madam Mao didn’t live with Mao. In his last ten years, Mao lived by himself — except for his personal secretaries, nurses, and

orderly. Behind the communist-god mask, Mao must have been a solitary man seeing his dream of the grandest empire slipping

away, not prepared to lead the country into the twentieth century, yet anxious to prove himself an emperor greater than all

those before. So he wielded such terms as “class struggle” and “proletarian dictatorship,” launching one political movement

after another, stifling all the opposition voices, until things came to a head during the Cultural Revolution. At night, however,

surrounded by the ancient books, paranoid of “capitalist roaders” who would try to usurp his power and “restore capitalism,”

Mao suffered from insomnia, hardly able to move because of his failing health…

Chen leaned down, touching the bed. A wooden-board mattress, as he had read in those memoirs, which claimed that Mao, working

for the welfare of the Chinese people, cared little about his personal comfort. Chen wondered whether Mao had ever thought

of Shang while on this bed.

Chen turned to look at the bathroom. In addition to the standard toilet, there was another one on the floor, shaped like a

porcelain basin, over which one had to squat — specially designed for Mao, who must have carried with him to the Forbidden City

his habit acquired as a farmer from a Hunan village.

It was another puzzling detail, but not all details would be relevant to his investigation. He hadn’t been able to establish

a connection, he thought, between himself as investigator and Mao as a suspect. Instead, he came to find himself in the presence

of another man, long dead and mysterious, but not the god Chen remembered from his school years.

Carrying the large envelope in his hand, Chen moved out into the garden. There seemed to be something sacrilegious about reading

the book Ling sent him while in Mao’s room. But he wanted to read it here instead of back at the hotel, while looking up at

the tilted eaves of the palace shimmering in the summer foliage, as if the location made a difference.

He perched himself on a slab of rock, on which Mao might have sat many a time. A stone

kylin

that had once escorted the emperors here stared at him. Lighting a cigarette, he remembered Mao was a smoker too — a heavier

one. Chen hadn’t the slightest desire to imitate Mao.

Sure enough, as he had guessed, the large envelope contained the book written by Mao’s personal doctor. There was another

envelope inside, smaller and sealed — probably the love poems written for Ling, long ago. He wasn’t going to read them at the

moment. So he opened the book, turning to the introduction. The author claimed to have served as Mao’s personal physician

for over twenty years, to know the intimate details of Mao’s life.

Instead of reading from the beginning, Chen moved to the index at the end. To his disappointment, there was no listing for

Shang. Leafing through the book, he tried to find anything relevant.

The book didn’t focus exclusively on the personal life of Mao. The doctor also wrote about his own life, from an idealistic

college student to a sophisticated survivor in those years of power struggle. For common readers, however, the appeal of the

book lay in the description of Mao’s life — of an emperor both in and out of the Forbidden City. The chapter Chen was reading

happened to be about Mao traveling around luxuriously in a special train. In the train, he actually took a young attendant

named Jade Phoenix to bed. She was only sixteen or

seventeen at the time. Afterward, he brought her back to the Central South Sea as his personal secretary. She eventually became

more powerful than the politburo members, for she alone understood what he mumbled after his stroke, being one of few he could

really trust. But she was only one of the many “favored” by Mao, who actually picked up women all over the country, in a variety

of circumstances, including at those balls arranged for him in Shanghai and in other cities.

Mao seemed to have a preference for young girls with little education, not intelligent or sophisticated —

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher