![The Rembrandt Affair]()

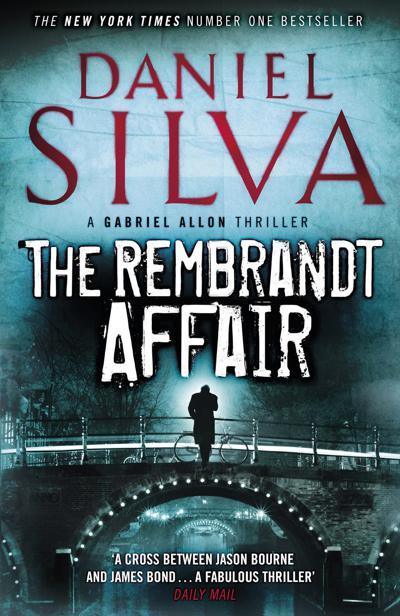

The Rembrandt Affair

back to Gabriel and Chiara and said, “But surely you didn’t come all the way to Mendoza to listen to me condemn my father.”

“Actually, I came because of this.”

Gabriel placed a photograph of Portrait of a Young Woman in front of Voss. It lay there for a moment untouched, like a fourth guest who had yet to find cause to join the conversation. Then Voss lifted it carefully and examined it in the razor-sharp sun.

“I’ve always wondered what it looked like,” he said distantly. “Where is it now?”

“It was stolen a few nights ago in England. A man I knew a long time ago died trying to protect it.”

“I’m truly sorry to hear that,” Voss said. “But I’m afraid your friend wasn’t the first to die because of this painting. And unfortunately he won’t be the last.”

32

MENDOZA, ARGENTINA

I n Amsterdam , Gabriel listened to the testimony of Lena Herzfeld. Now, seated on a grand terrace in the shadow of the Andes, he did the same for the only child of Kurt Voss. For his starting point, Peter Voss chose the night in October 1982 when his mother had telephoned to say that his father was dead. She asked her son to come to the family home in Palermo. There were things she needed to tell him, she said. Things he needed to know about his father and the war.

“We sat at the foot of my father’s deathbed and spoke for hours. Actually, my mother did most of the talking,” Voss added. “I mostly listened. It was the first time that I fully understood the extent of my father’s crimes. She told me how he had used his power to enrich himself. How he had robbed his victims blind before sending them to their deaths at Auschwitz, Treblinka, and Sobibor. And how, on a snowy night in Amsterdam, he had accepted a portrait by Rembrandt in exchange for the life of a single child. And to make matters worse, there was proof of my father’s guilt.”

“Proof he had acquired the Rembrandt through coercion?”

“Not just that, Mr. Allon. Proof he had profited wildly from history’s greatest act of mass murder.”

“What sort of proof?”

“The worst kind,” said Voss. “Written proof.”

Like most SS men, Peter Voss continued, his father had been a meticulous keeper of records. Just as the managers of the extermination centers had maintained voluminous files documenting their crimes, SS-Hauptsturmführer Kurt Voss had kept a kind of balance sheet where each of his illicit transactions was carefully recorded. The proceeds of those transactions were concealed in dozens of numbered accounts in Switzerland. “Dozens, Mr. Allon, because my father’s fortune was so vast he thought it unwise to keep it in a single, conspicuously large account.” During the final days of the war, as the Allies were closing in on Berlin from both east and west, Kurt Voss condensed his ledger into one document detailing the sources of his money and the corresponding accounts.

“Where was the money hidden?”

“In a small private bank in Zurich.”

“And the list of account numbers?” asked Gabriel. “Where did he keep that?”

“The list was far too dangerous to keep. It was both a key to a fortune and a written indictment. And so my father hid it in a place where he thought no one would ever find it.”

And then, in a flash of clarity, Gabriel understood. He had seen the proof in the photos on Christopher Liddell’s computer in Glastonbury—the pair of thin surface lines, one perfectly vertical, the other perfectly horizontal, that converged a few centimeters from Hendrickje’s left shoulder. Kurt Voss had used Portrait of a Young Woman as an envelope, quite possibly the most expensive envelope in history.

“He hid it inside the Rembrandt?”

“That’s correct, Mr. Allon. It was concealed between Rembrandt’s original canvas and a second canvas adhered to the back.”

“How long was the list?”

“Three sheets of onionskin, written in my father’s own hand.”

“And how was it protected?”

“It was sealed inside a sheath of wax paper.”

“Who did the work for him?”

“During my father’s time in Paris and Amsterdam, he came in contact with a number of people involved in Special Operation Linz, Hitler’s art looters. One of them was a restorer. He was the one who devised the method of concealment. And when he’d finished the job, my father repaid the favor by killing him.”

“And the painting?”

“During his escape from Europe, my father made a brief stop in Zurich to meet

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher