![The Rembrandt Affair]()

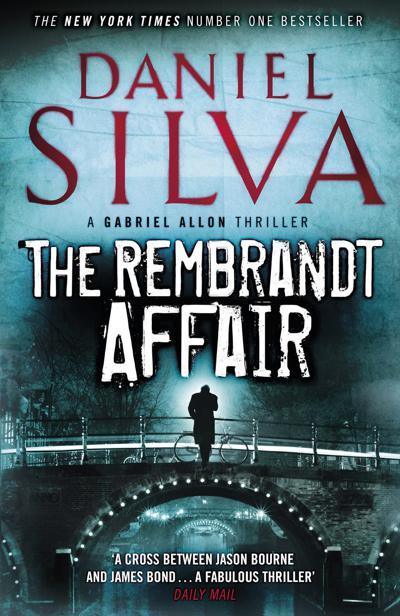

The Rembrandt Affair

San Telmo district of Buenos Aires, and the name of a certain former colonel who had worked for the Argentine secret police during the darkest days of the Dirty War. The most intriguing aspect of the communication, however, was the date of the operatives’ return home. They were scheduled to leave Buenos Aires the following night. One would take Air France to Paris; the other, British Air to London. No reason for their separate travel was given. None was needed. The two operatives were both veterans and knew how to read between the lines of the cryptic communiqués that flowed from corporate headquarters. An account termination order had been handed down. Cover stories were being written, exit strategies put in place. It was too bad about the woman, they thought as they glimpsed her briefly standing on the balcony of her hotel room. She really did look quite lovely in the Argentine moonlight.

34

BUENOS AIRES

O n the night of August 13, 1979, Maria Espinoza Ramirez, poet, cellist, and Argentine dissident of note, was hurled from the cargo hold of a military transport plane flying several thousand feet above the South Atlantic. Seconds before she was pushed, the captain in charge of the operation slashed open her abdomen with a machete, a final act of barbarism that ensured her corpse would fill rapidly with water and thus remain forever on the bottom of the sea. Her husband, the prominent antigovernment journalist Alfonso Ramirez, would not learn of Maria’s disappearance for many months, for at the time he, too, was in the hands of the junta’s henchmen. Had it not been for Amnesty Inter national, which waged a tireless campaign to bring attention to his case, Ramirez would almost certainly have suffered the same fate as his wife. Instead, after more than a year in captivity, he was freed on the condition he refrain from ever writing about politics again. “Silence is a proud tradition in Argentina,” said the generals at the time of his release. “We think Senor Ramirez would be wise to discover its obvious benefits.”

Another man might have heeded the generals’ advice. But Alfonso Ramirez, fueled by rage and grief, waged a fearless campaign against the junta. His struggle did not end with the regime’s collapse in 1983. Of the many torturers and murderers Ramirez helped to expose in the years afterward was the captain who had hurled his wife into the sea. Ramirez wept when the panel of judges found the captain guilty. And he wept again a few moments later when they sentenced the murderer to just five years in prison. On the steps of the courthouse, Ramirez declared that Argentine justice was now lying on the bottom of the sea with the rest of the disappeared. Arriving home that evening, he found his apartment in ruins and his bathtub filled with water. On the bottom were several photos of his wife, all of which had been slashed in half.

Having established himself as one of the most prominent human rights activists in Latin America and the world, Alfonso Ramirez turned his attention to exposing another tragic aspect of Argentina’s history, its close ties to Nazi Germany. Sanctuary of Evil, his 2006 historical masterwork, detailed how a secret arrangement among the Perón government, the Vatican, the SS, and American intelligence allowed thousands of war criminals to find safe haven in Argentina after the war. It also contained an account of how Ramirez had assisted Israeli intelligence in the unmasking and capture of a Nazi war criminal named Erich Radek. Among the many details Ramirez left out was the name of the legendary Israeli agent with whom he had worked.

Though the book had made Ramirez a millionaire, he had resisted the pull of the smart northern suburbs and still resided in the southern barrio of San Telmo. His building was a large Parisian-style structure with a courtyard in the center and a winding staircase covered by a faded runner. The apartment itself served as both his residence and office, and its rooms were filled to capacity with tens of thousands of dog-eared files and dossiers. It was rumored that Ramirez’s personal archives rivaled those of the government. Yet in all his years of rummaging through Argentina’s dark past, he had never digitized or organized his vast holdings in any way. Ramirez believed that in clutter lay security, a theory supported by empirical evidence. On numerous occasions, he had returned home to find his files in disarray, but none of his important

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher