![The Six Rules of Maybe]()

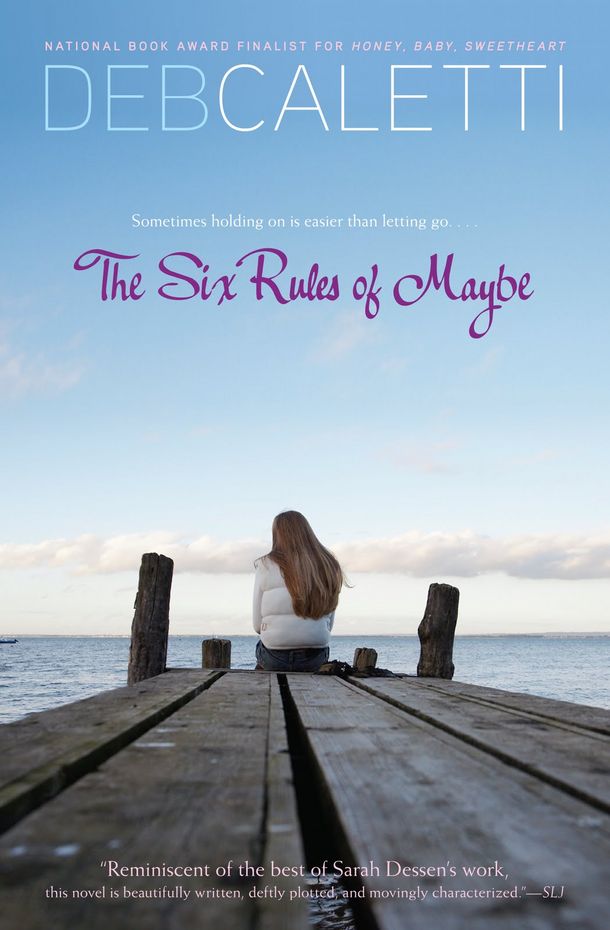

The Six Rules of Maybe

felt too busy, as if it were an old room being moved into or out of—boxes about to be opened or shut, things being shifted around, movers bringing in new furniture there wasn’t a place for yet. I decided to surprise my mother and Juliet by not being such a loser introvert and by going over to Nicole’s after all. Her parents’ restraining orders sounded kind of peaceful. I left Mom a note, grabbed my backpack, and headed out.

As I walked down the drive, my eye caught on something over by the tire of Hayden’s truck—a sheet of paper folded and folded again until it was a fat chunk. When I leaned down to pick it up, I also saw the sticker on his back bumper: The only good clown is a dead clown . Ha. Another person with clown fear who was actually doing something about it.

Before I could open the paper to see what it was, I noticed old Clive Weaver across the street, on his hands and knees in his driveway. I liked Clive Weaver. I maybe even loved him. Even if he was always doing some loud, industrious thing like chainsawing tree branches or vacuuming his car at annoying hours on Saturday mornings, he made me feel happy when I saw him. He always gave a hearty wave and said hearty things to me like “Go give ’em hell today!” When he walked his dog, Corky, he let Corky lead, which sometimes meant that you’d find Clive Weaver in your hedges or up other people’s driveways. Right then, he was crouched next to his boxy white Jeep with no backseat, (which he’d bought when the postal service sold its old fleet), peering underneath. He was wearing his usual attire—blue shorts, blue shirt, and knee socks, as close as you could get to the mail carrier outfit he’d worn for thirty-five years without actually being the mail carrier outfit he’d worn for forty-five years.

“Mr. Weaver?” I called.

“I had them a minute ago,” he said.

“Did you lose something?” I asked.

He looked over at me, startled.

“My keys. I had them right here,” he said. His white hair stood out in an alarmed fashion. It was usually combed straight across.

“There.” I pointed. “In your hand.”

He looked down, his mouth gaping at the surprise appearance of the keys. He was really worrying me lately. His old-guy vigor and capability seemed to be seeping from him daily, turning into something confused and feeble.

“That happens to me all the time,” I lied.

“Goddamn,” he muttered.

“See you, then,” I said.

“See you,” he said to his keys.

Clive Weaver went to his mailbox next and opened it with a tiny key on his key ring. I hoped something was in there. He loved it when he got mail. You could tell. Even if it was some Domino’s Pizza ad or one of the endless notepads or calendars or letters from Yvonne Yolanda, Your Friend in the Real Estate Business, he seemed pleased. He’d walk off looking at the envelope with a smile and a bounce in his step, as if he were walking on promises. Most of all, I think, he loved to hate getting his electrical bill. He’d shake his fist at the envelope. “Roscoe Oil!” he’d say. “Those bastards!” But today, nothing. I heard the sad metal door shut against the sad metal box.

I held the clump of paper in my hand and unfolded it as I stood there on the grass. It was a letter. Black ink and small block letters. Hayden’s handwriting. I had no proof of it, but I knew it inside, down deep and clear as day, the way you know all of the most truthful things. It said:

A little evidence of God …

Stars.

Raspberries.

Sand dollars.

The need to make music and art.

Sight. Insight.

Tree rings.

Evolution, yes.

Genius, invention, and the brain itself.

Repetition of design, and on the flip side, variety of design.

The sea.

Color.

Language.

Babies.

And most of all … you, my beautiful Juliet.

For a moment, I could barely breathe. I held the note in my hand as Mr. Weaver shuffled inside; as Fiona Saint George shuffled outside, wearing all black and grasping a box of chalk; as the Martinellis’ dog, Ginger, squatted by the juniper bush; and as Ally Pete-Robbins’s banner blew in the breeze, reminding anyone who might forget such a thing that it was spring.

Some place opened in me that I didn’t know could open. I felt a rip, a thing being torn, and underneath, something laid bare that I’d never felt before, some sort of longing. The words on the page were as beautiful as any I had ever seen. They were an offering, a gift held out in careful, cupped hands. They

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher