![The Six Rules of Maybe]()

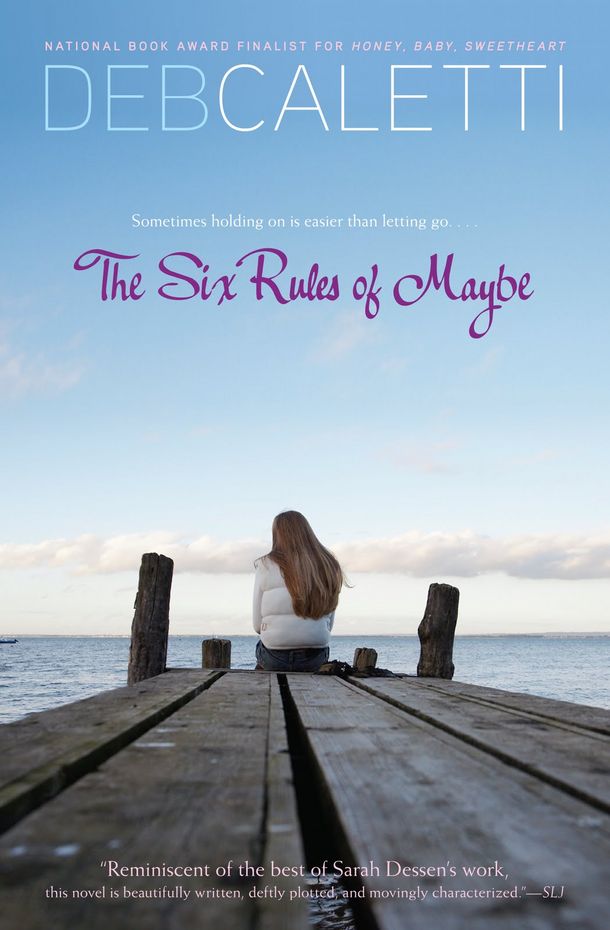

The Six Rules of Maybe

listen hard. It was a new way of seeing things, and I had held fast for a very long time to my old way.But it made sense to me, the simplest sort. It was possible, maybe, to have facts in your mind that weren’t facts at all. You could build a whole life’s story on false assumptions. You could make truths out of untruths and untruths out of truths. Until you spoke them, really said them out loud or checked for sure, you may not have known which were which.

“Oh sweetheart, I am so, so sorry. I didn’t know. You were just so capable .”

“You’re going to marry Dean,” I said.

“No, honey. I broke up with Dean. I was so late that night because I was telling Dean I didn’t want to see him again.”

“You broke up with him?”

“I kept wishing it would be different. Trying to make it something it would never be. I always hated giving up. But giving up isn’t always the worst thing. It isn’t. It’s gotten a bad name. Giving up can be good . There are better places for my hope. Much better places.”

“Mom …” The word was relief and pleading and understanding and a million other things. I wasn’t capable right then. I set my capability down, and she held me. She patted my back like a baby but I didn’t mind. I felt exhausted from too much emotion. From having the ways I had seen things detonated and shattered. I would have to look again. You could try and understand people, you could read books and understand words and concepts and ideas, but you could never understand enough or have enough knowledge to keep away the surprises that both fate and human beings had in store. This was too bad, I thought, but this was good, too.

We were both exhausted, we agreed. And so Mom and I did the thing that we did sometimes—our own thing—we turned on a movie andshe made popcorn, and we ate it and watched, sitting beside each other.

“It’s funny,” she said. The psycho killer in the movie had been finally brought down by the young girl and her kid brother. “No one is ever quite as strong or as weak as you’d think.”

Chapter Twenty-five

K evin Frink and Fiona Saint George were somewhere in California when Kevin Frink’s Volkswagen broke down. My mother heard this from Mrs. Martinelli, who heard this from Mrs. Saint George. I could imagine Kevin Frink sweating then, somewhere in the heat and dry air, unfamiliar yellow hills around them. Fiona would have used her family plan cell phone to call her parents for help. Fiona Saint George and Kevin Frink were on their way home now, in a rental car with air-conditioning and room to recline their seats. Mr. Saint George had wired her money, because that’s what you did when you loved, right or wrong. When you were gentle, loving people who studied ocean creatures, or who created scrapbooks of faraway places, or who wrote notes that were really poetry, or who folded paper cranes and more paper cranes, you gave when maybe you shouldn’t give, gave even when your very house had been blown to a million pieces.

Or else, you gave until you finally couldn’t anymore.

It had been five days since the blast, five days that Juliet had been gone with Jitter, and five days since I’d last seen the back of Zeus disappear around that corner. I can’t tell you how badly I wanted to see him, to see his funny face, his person-not-person self looking back at me with eager eyes that seemed to wonder what great thing was coming his way next. I would have given anything to see him again. Anything.

You were supposed to have hope, right? You were supposed to respect its power and hold on. And so I did. I held, and held, and let hope fill me. But as the days went on, it seemed I could be holding for a long, long time. Hope could be the most powerful thing or the most useless.

The Salvation Army truck came and got the last of the Martinellis’ belongings. They didn’t even need a moving van. Rob’s Taxi (basically Rob Millencamp in Rob Millencamp’s Ford Taurus) came and picked them up to go to the airport; Rob waited patiently at the curb reading How to Win at Poker as Mrs. Martinelli rolled her luggage down the walk. Mr. Martinelli wore that Hawaiian shirt again, and he was beaming and bouncing all over the place, pinching Mrs. Martinelli on the butt. She got teary for a moment as she shut the door, but only for a moment. Maybe it was even my imagination.

Mom and I both said good-bye. Mrs. Martinelli had taught her how to prune rosebushes and had given her

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher