![The Six Rules of Maybe]()

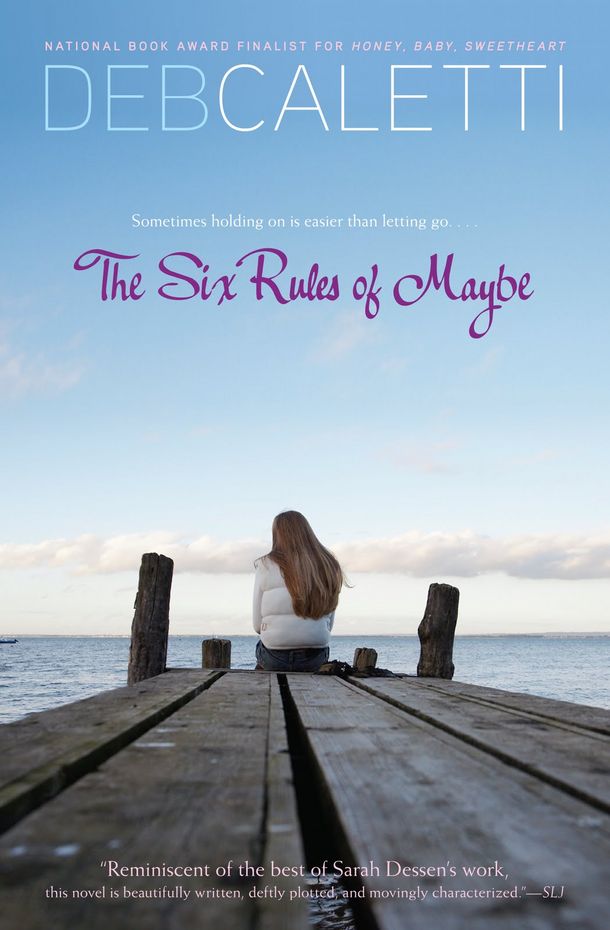

The Six Rules of Maybe

degree to which you hoped and wished for a good outcome multiplied by how wrong it all went equaled the amount of despair.

We walked across the parking lot of Johnny’s Market, with its jarring sounds of clanging carts and small children and into the store itself with its jarring bright lights and jarring music and jarring bodies reaching for containers of yogurt and plastic bags to put broccoli in. Every color felt too bright and every sound too loud. Bad things make the regular world too much to bear. It’s too simple then. Its simplicity shouts. A tube of toothpaste is so regular it makes your heart break. A cereal box does.

We were there in the international foods aisle, with its mundane assortment of the no longer exotic—refried beans, soy sauce, Thai food in a box. Hayden reached for a bag of rice and added it to the basket he carried in one hand.

“Onion,” he read off the list, and we continued down the aisle, and that’s when I saw him, the lean coyote body, the thin angular face capable of destroying our lives. Buddy Wilkes just walking past the aisle, fast, too, like he had places he needed to get to.

It hadn’t occurred to me that she was right here somewhere, still on Parrish Island. I’d have guessed they would have had the decency to at least go away for a while to some stupid motel, some loser house on the mainland rented by one of Buddy Wilkes’s loser friends. But I never imagined her here, her head on a pillow not five minutes away from Hayden’s agony, sleeping in some pull-out bed in Buddy Wilkes’s apartment over the Friedmans’ garage as Hayden lay awake under our own roof.

My heart stopped—I hoped Hayden hadn’t seen him. I would veer us away, steer us toward the frozen foods, something, just not where he was or maybe, God, her, too. Would she be that cruel toappear in public like that? Could she be right here, picking out some pack of cinnamon gum? She had been cruel enough to leave; that was the thing.

Maybe Juliet had some stupid craving Buddy was now responsible for, or maybe he came to get more cigarettes, I didn’t know. He’d better be fast , I thought, and I grabbed Hayden’s sleeve to steer him left instead of right. I hadn’t looked at Hayden’s face, though, until that moment. He was looking down the way Buddy Wilkes had gone, eyes fixed. His face looked much older than I had ever seen. He lifted the basket and renewed his grip on it in a way that made the contents clatter against each other. He cleared his throat as if he were about to speak.

“Come on,” I said.

We just stood there at the front of the store, where the lines formed, where people read the fronts of the magazines and plucked containers of mints to add to their loot on the rolling black mat. A toddler tried to stand in a cart, and his mother shoved him down. Mrs. Sheen, the attendance lady at our school, said a brisk Excuse me to us to indicate we stood between her and the tortilla chip display that was the priority of her life right then.

“Hayden, come on,” I said again, as Mrs. Sheen’s arm reached pointedly around us.

“I think I saw … ,” he said. His voice was husky.

“Let’s get out of here.”

But Hayden didn’t listen. Instead, he set down our basket right there, right in the center of the aisle, and he strode toward the bakery department where Buddy Wilkes was headed. God, oh God , I thought. We were going to have a scene, a scene in Johnny’s Market, right near the croissants and freshly baked pies. I didn’t know what Hayden was capable of, and if I’d have imagined a situation likethis, I’d have guessed him to return to his truck and start it up and drive home. I wouldn’t have guessed his angry stride, his tense jaw. I thought of what he had said about his father—a bad man. I wondered about the places in him we didn’t know, in him or in anyone, that stayed undiscovered until what was most precious had been taken.

“Hey!” he called. His voice, which had been flat and emotionless for days, seemed full and roaring, like that fire in the Saint George garage. “Hey!”

I followed. He was walking fast enough that up ahead I could see the back of Buddy Wilkes, who looked so suddenly less of everything that Hayden was. Less strong, less intelligent with his pale face and stupid grin, less attractive, less of a man in all ways. Buddy Wilkes turned to the sound of Hayden’s voice. He held a box of doughnuts in his hand, just doughnuts. The kind that

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher