![The staked Goat]()

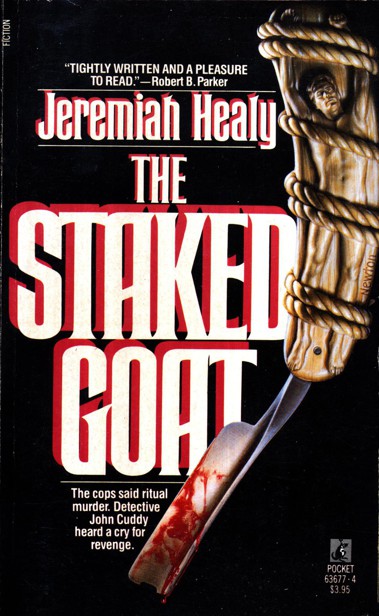

The staked Goat

index finger. Martha simply sat, stoically staring at the coffin.

At five o’clock, a young heavyset girl of perhaps nineteen came in. She looked at us and began sniffling. She fumbled in her bag for some Kleenex and got to it just as the tide broke. I got up and guided her to a chair.

Her name was Trudy Murcher, and she was the secretary for the salesmen at Straun Steel. She saw the newspaper story and was so shocked, and had tried to call Martha at home, and got Larry, and felt she had to...

She lasted seven minutes and then had to leave.

At 5:40, a dumpy guy with a blue polyester sports jacket and polyester houndstooth pants came in. He introduced himself as Norm Denver and had been a salesman with Al. Norm apologized for coming so late and having to leave so soon, but he’d just come from an all-day meeting and had to get home. He had Scotch on his breath and a stain on his tie. The stain dated from the late seventies.

He wished Martha luck, stood uneasily in front of the coffin for a couple of seconds, and then turned to go. I caught him in the foyer as he was buttoning up and an after-work rush was heading into another wake.

”Mr. Denver,” I said, ”can I speak with you for a moment?”

”Jeez,” he said, looking down and fumbling with his second button, ”I’m late now. Gloria’ll kill me if I don’t get home to see the brats into bed.”

I waited until he looked up at me. I said evenly, ”I need to speak with someone about Al.”

He exhaled. I wondered how he could smell like an exhaust fan at a Seagram’s factory and not show it.

”O.K.,” he said, abandoning the button, ”but honest, just a couple of minutes, O.K.?”

”Thank you,” I said, and we edged into a corner of the foyer where there was no table or chair.

”I need to speak with whoever is in charge of benefits at Straun.”

He looked a little furtive. ”Benefits?”

”Yes. Like life insurance, survivors’ health care, that kind of thing.”

He swallowed and began again with buttons. ”Maybe you better call the company.”

I slapped his hand away.

”Hey,” he said, rubbing the slapped hand with his other. ”What’s the idea?”

”The idea is you tell me who to contact at Straun. Is there something wrong with that?”

”You can’t reach anybody until Monday, anyways. Look,” he said, lowering his voice, ”I don’t want no trouble. I got a job, and I do O.K., and that’s a lot more’n most have in this town right now, O.K.?”

”Go ahead.”

”Straun—old man Straun, there’s a son too, a lawyer, but he works for the company—old man Straun hired Al because he heard Jews were supposed to be good at sellin’ stuff, you know. Now, Al, he wasn’t. He was an O.K. guy, but he didn’t wanna do the stuff you gotta do to close sales with the customers. You know anything about steel?”

”Not much.”

”Well, the big boys, the heavy steel and sheet producers, are gettin’ murdered by the Japs and all dumping in our markets. Dumping in the sense of sellin’ steel in our markets below our cost, I mean American companies’ cost, to make the stuff. When the big boys hurt, we hurt, ‘cuz our best way of gettin’ sales is by piggybacking the reps of the big boys into the customer. To do that, you gotta, well, sort of compensate the reps, you know?”

”I’m getting the picture.”

”O.K. So Al doesn’t like to do that stuff. So AI thinks that after Straun’s been in business somethin’ like fifty-three years—the company was started by old man Straun’s father in the twennies—and survived depressions and a war with Straun’s fuckin’ cousins, Al thinks he can do it different. Al thinks he can go in cold and sell to the generals—the guys who build the buildings that use our stuff—direct, by personal contact. Well, he thinks wrong. He couldn’t do it, you couldn’t do it. Nobody could do it.”

”All of which adds up to what?”

Norm stole a look at his watch and grimaced. ”All of which adds up to he wasn’t making his draw, follow? He wasn’t closing the sales to cover his pay. He was overdrawn like at the bank.”

I felt a cold wave but nobody had opened the door.

”His insurance?”

”Buddy, I gotta guess that Al lost all that months ago. The only thing keepin’ him on was old man Straun’s stubbornness. He’d made the decision to hire him, and that meant he couldn’t admit he was wrong by firin’ him. But stubborn don’t mean stupid, and it sure don’t

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher