![The staked Goat]()

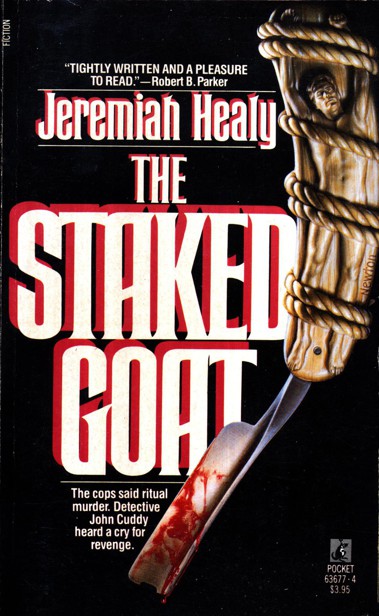

The staked Goat

me outta here. Get me out!” He was yelling before he could have heard me coming. ”Mother of God, sweet Mary, get me out, get me out!”

I grabbed him by the left arm and yanked him over to face me. Although it was barely forty degrees outside, and not much warmer inside when I had entered, the sweat from my fire-sided forehead was pouring down my nose and into my eyes.

”Who, fire man,” I asked the lump. ”Who paid the price for this one?”

”What’s wrong with you, man? Get me outta this place. Please God, fuckin’ Jesus, get me out!”

”You’re talkin’ like a baked potato, fire man,” I said softly. I looked behind me, then grabbed his hair and twisted his head to assure him the same perspective. ”That flame looks twenty, maybe thirty feet closer than it was the first time I asked the question. You can’t outrun it, fire man. Now who was it paid your price?”

Lump’s face was contorting. I’ve yet to meet a torch who wasn’t scared blind, and rightly so, of uncontrolled flames. ”The owner. The bastard owner. Weeks. Harvey fuckin’ Weeks! For God’s sake, man, get me out, get me out!”

I dragged him by the bad arm till the screaming, actually one long scream, stopped. Then I slung him over my shoulder and headed for the window. The Coopers must have heard me going down their stairs, because the first lonely siren hit my ears just as I shoved him through the window.

The lump’s name turned out to be Joseph D’Amico. I attended his bail hearing three days after the fire, Joseph himself being under guard in a hospital room. His lawyer’s name was Thomas Smolina, a short, fiftyish man in a blue polyester suit that affected a Glen plaid. The lawyer was trying to persuade Judge Harry J. Elam, then chief justice of the Boston Municipal Court, that his ”Joey” should be released on $20,000 bail, cash equivalent. The ”cash equivalent” part meant that instead of a bail bondsman putting up $20,000 for a nonrefundable premium of $2,000, the D’Amico family, arrayed in the first row of the courtroom, could put up two thousand cash themselves, thus saving the bailbond premium so long as Joey showed up at the trial. Smolina argued that the D’Amico family, solid citizens of Boston for thirty-nine years, provided the sort of stable base that would ensure that his client would attend the trial. Lawyer ticked off each family member, who stood up and nodded to the judge as his or her name was mentioned. Smolina reached Joey’s brother, Marco, a man about my size and build in a black turtleneck. Marco nodded and then, as he sat back down, swiveled his head to glare at me. I smiled politely and thought that Joey’s lawyer should have screened Marco from the family portrait presented to the judge.

Judge Elam thanked Smolina and turned to the assistant district attorney. She stood and began speaking without needing to identify herself. She pointed out the defendant’s track record of four missed trials, one for armed robbery, one for arson. She mentioned Craigie’s blackened and cottony body, escalating the expected indictments to felony/murder. She also mentioned codefendant Harvey Weeks’ suicide attempt upon hearing the police come knocking at his door. She felt $250,000, no cash equivalent, was more appropriate. In the front row, Mother D’Amico began to whimper, none too softly. Marco put his arm around her shoulders and pulled her close to him, none too gently.

Judge Elam asked Smolina if he had anything to add. ”He’s not a bad boy, your honor. And he’s from a good family,” said lawyer, gesturing with a sweep of his hand that reluctantly included Marco.

Judge Elam set bail at $250,000, no cash equivalent.

I wanted to speak briefly with the assistant district attorney, who had in front of her three or four more manila files to deal with that morning. I stayed seated and debated waiting for her to finish. The D’Amicos, lawyer in lead, came down the middle aisle. Father D’Amico was consoling his wife, Marco hanging back a bit. As Marco pulled even with my row, he paused and leaned over to me. He muttered, ”If I was you, I’d have somebody else start my car for me,” and then continued on.

I decided I would wait to speak with the assistant district attorney.

She was about 5-foot-8, slim in a two-piece, skirt-and-jacket, gray suit. She had long black hair pulled into a bun. From where I sat in the courtroom, I could see her face only in partial profile. She

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher