![The Tortilla Curtain]()

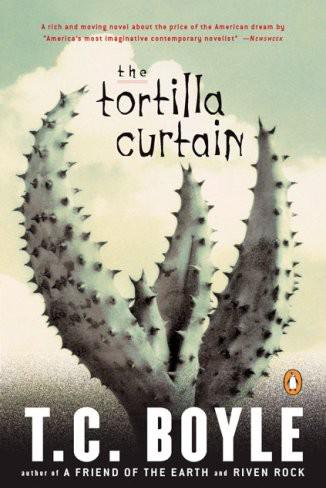

The Tortilla Curtain

tell three-quarters of everything about a house by the way it smelled--condition, upkeep, what kind of people owned it, whether the roof leaked or the basement flooded. What you didn't want was that dead tomblike smell of a shut-up house, as if it were a funeral parlor, or anything that smelled of dry rot or chemicals or even paint. Cooking odors were anathema. Ditto the stink of animals. She'd listed one house--one of her few failures--in which an old lady had died surrounded by thirty-two cats that had pissed, crapped and sprayed on every surface available, including the ceilings. The only hope for that place was to burn it down.

Now, stepping into the Matzoobs', the first thing Kyra did was close the door behind her and take a good long lingering sniff. Then she exhaled and tried it again, alert to every nuance, her nose as keen as any connoisseur's. Not bad. Not bad at all. There was maybe the faintest whiff of cooking oil from some long-forgotten meal, a trace of dog or cat, mothballs maybe, but she couldn't be sure. It helped that the place was empty--when it first went on the market eight months ago the Matzoobs were still here, the halls, closets and bathrooms steeping in their own peculiar odor. And to call the odor “peculiar” wasn't being judgmental, not at all--it was merely descriptive. Every family, every house, had its own aroma, as unique and individual as a thumbprint.

The Matzoobs' was a rich ferment of smell, ranging from the perfume of the fresh-cut flowers Sheray Matzoob favored to the pungent stab of garlic and coriander Joe Matzoob had learned to use in his gourmet cooking classes and the festering sweat socks of Matzoob Jr., the basketball star. It was a homey smell, but too complicated to do anybody any good. And the furniture was a nightmare. Big cumbersome pieces finished in an almost ebony stain that seemed to drink up what little light penetrated the thick blanket-like curtains Sheray Matzoob had inherited from her mother. And the portraits--they were something else altogether. Big, crude, cheesy things that made the Matzoobs look like ghouls, with gold-tinted frames and paint so thick it might have been applied with a butter knife.

But now the place was empty, and that suited Kyra just fine. Once in a while you'd get a place that was so exquisitely furnished you'd ask the sellers to leave their things in place until the house was in escrow, but that was rare. Most people had no taste. No dream of it. Not a clue. And yet they all thought they had it--were smug about it even--and they'd walk right out the door because of an unfortunate lamp or a deep plush carpet in a shade they couldn't fathom. All things considered, Kyra preferred it this way--a neutral environment, stripped to the essentials: walls, floors, ceilings and appliances. A vacant house became hers in a way--it had been abandoned, deserted, left in her hands and hers alone, and sometimes the sellers were off in another state or country even--and she couldn't help feeling proprietorial about it. Sometimes, making the rounds of her houses--she had forty-six current listings, more than half of them unoccupied--she felt like the queen of some fanciful country, a land of high archways, open rooms and swimming pools that would have made an inland sea if stretched end-to-end across her domain.

There was a broom in the garage--practically the only thing left there, if you discounted the two trash cans and a box of heavy-duty garbage bags. Kyra swept the water from the front porch and then went into the bathroom in the master suite to freshen up her face before Sally Lieberman from Sunrise arrived with her buyers. The bathroom was dated, unfortunately, by its garish ceramic tiles, each with the miniature yellow, blue and green figure of a bird emblazoned on it, and by the tarnished faux-brass fixtures and cut-glass towel racks that gave the place the feel of the ladies' room in a Mexican restaurant. Ah, well, each to her taste, Kyra was thinking, and then she caught a good look at herself in the mirror.

It was a shock. She looked awful. Haggard, frowsy, desperate, like some stressed-out Tupperware hostess or something. The problem was her nose. Or, actually, it was Sacheverell and the night she'd spent, but all the grief and shock and exhaustion of the ordeal was right there, consolidated in her nose. The tip of it was red--bright red, naming--and when the tip of her nose was red it seemed to pull her whole face in on itself

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher