![The Tortilla Curtain]()

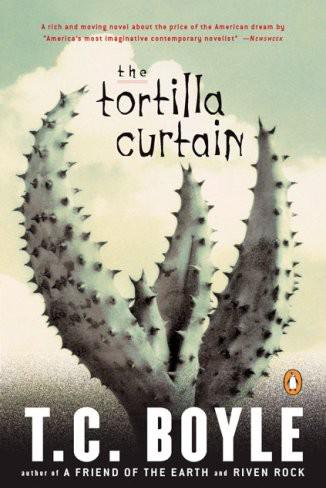

The Tortilla Curtain

swollen with emotion, the heavy breath of the freezer swirling ghostlike round her bare legs. Delaney didn't know what to say. He felt guilty somehow, culpable, as if he'd killed the dog himself, as if the whole thing were bound up in venality, lust, the shirking of responsibility and duty, and yet at the same time the scene was irresistibly erotic. Despite himself, he began to stiffen. But then, as Kyra stood there in a daze and the freezer breathed in and out and the pale wedge of light from the open door pressed their trembling shadows to the wall, there came a clacking of canine nails on the polished floorboards, and Osbert, the survivor, poked his head in the door, looking hopeful.

It was apparently too much for Kyra. The relic disappeared into the depths of the freezer amid the peas and niblet corn and potato puffs, and the door slammed shut, taking all the light with it.

You didn't move property with a long face and you didn't put deals together if you could barely drag yourself out of bed in the morning-especially in this market. Nobody had to tell Kyra. She was the consummate closer--psychic, cheerleader, seductress and psychoanalyst all rolled in one--and she never let her enthusiasm flag no matter how small the transaction or how many times she'd been through the same tired motions. Somehow, though, she just couldn't seem to muster the energy. Not today. Not after what had happened to Sacheverell. It was only eleven in the morning and she felt as worn and depleted as she'd ever been in her life. All she could think about was that grisly paw in the freezer, and she wished now that she'd let Delaney go ahead with his deception. He would have buried the evidence in the morning and she'd never have been the wiser--but no, she had to see for herself, and that little foreleg with its perfectly aligned little toenails was a shock that kept her up half the night.

When she did finally manage to drift off, her dreams were haunted by wolfish shapes and images of the hunt, by bared fangs and flashing limbs and the circle of canny snouts raised to the sky in primordial triumph. She awoke to the whimpering of Osbert, and the first emotion that seized her was anger. Anger at her loss, at the vicissitudes of nature, at the Department of Fish and Game or Animal Control or whatever they were called, at the grinning stupid potbellied clown who'd put up the fence for them--why stop at six feet? Why not eight? Ten? When the anger had passed, she lay there in the washed-out light of dawn and stroked the soft familiar fluff behind the dog's ears and let the hurt overwhelm her, and it was cleansing, cathartic, a moment of release that would strengthen and sustain her. Or so she thought.

At eleven-fifteen she pulled up in front of the house she was showing--the Matzoob place, big and airy, with a marble entrance hall, six bedrooms, pool, maid's room and guesthouse, worth one-point-one two years ago and listed at eight now and lucky to move for six and a half--and the first thing she noticed was the puddle of water on the front porch. Puddle? It was a pond, a lake, and the depth of it showed all too plainly how uneven the tiles were. She silently cursed the gardener. There had to be a broken sprinkler head somewhere in the shrubbery--yes, there it was--and when the automatic timer switched on, it must have been like Niagara out here. Well, she'd have to dig around in the garage and see if she could find a broom somewhere--she couldn't very well have the buyers wading through a pond to get in the house, not to mention noticing that the tiles were coming up and the porch listing into the shrubbery. And then she'd call the gardener. What was his name--she had it in her book somewhere, not the service she usually used, some independent the Matzoobs had been big on before they moved to San Bernardino--Gutiérrez? González? Something like that.

Kyra had no patience with incompetence, and here it was, staring her in the face. How the gardener could come back week after week and not notice something as obvious as an inch and a half of water on the front porch was beyond her, and the pure immediate unalloyed aggravation of it allowed her to forget Sacheverell for the moment and focus on the matter at hand, on business, on the moving of property. Nothing escaped her. Not a crack in the plaster, a spot of mold on the wall behind the potted palm or an odor that wasn't exactly what it was supposed to be.

Odors were the key. You could

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher