![The Tortilla Curtain]()

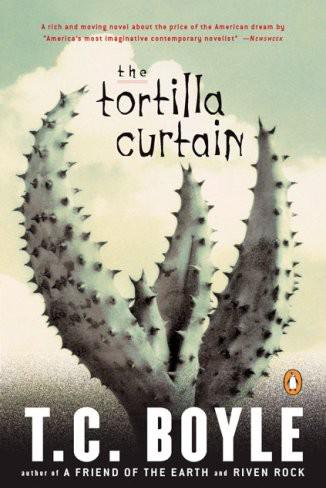

The Tortilla Curtain

below.

Delaney didn't remember getting back into the car, but somehow he found himself steering, braking and applying gas as he followed a set of taillights up the canyon, sealed in and impervious once again. He drove in a daze, hardly conscious of the air conditioner blasting in his face, so wound up in his thoughts that he went five blocks past the recycling center before realizing his error, and then, after making a questionable U-turn against two lanes of oncoming traffic, he forgot himself again and drove past the place in the opposite direction. It was over. Money had changed hands, there were no witnesses, and the man was gone, out of his life forever. And yet, no matter how hard he tried, Delaney couldn't shake the image of him.

He'd given the man twenty dollars--it seemed the least he could do--and the man had stuffed the bill quickly into the pocket of his cheap stained pants, sucked in his breath and turned away without so much as a nod or gesture of thanks. Of course, he was probably in shock. Delaney was no doctor, but the guy had looked pretty shaky--and his face was a mess, a real mess. Leaning forward to hold out the bill, Delaney had watched, transfixed, as a fly danced away from the abraded flesh along the line of the man's jaw, and another, fat-bodied and black, settled in to take its place. In that moment the strange face before him was transformed, annealed in the brilliant merciless light, a hard cold wedge of a face that looked strangely loose in its coppery skin, the left cheekbone swollen and misaligned--was it bruised? Broken? Or was that the way it was supposed to look? Before Delaney could decide, the man had turned abruptly away, limping off down the path with an exaggerated stride that would have seemed comical under other circumstances--Delaney could think of nothing so much as Charlie Chaplin walking off some imaginary hurt--and then he'd vanished round the bend and the afternoon wore on like a tattered fabric of used and borrowed moments.

Somber, his hands shaking even yet, Delaney unloaded his cans and glass--green, brown and clear, all neatly separated--into the appropriate bins, then drove his car onto the big industrial scales in front of the business office to weigh it, loaded, for the newspaper. While the woman behind the window totted up the figure on his receipt, he found himself thinking about the injured man and whether his cheekbone would knit properly if it was, in fact, broken--you couldn't put a splint on it, could you? And where was he going to bathe and disinfect his wounds? In the creek? At a gas station?

It was crazy to refuse treatment like that, just crazy. But he had. And that meant he was iilega!--go to the doctor, get deported. There was a desperation in that, a gulf of sadness that took Delaney out of himself for a long moment, and he just stood there in front of the office, receipt in hand, staring into space.

He. tried to picture the man's life--the cramped room, the bag of second-rate oranges on the streetcorner, the spade and the hoe. and the cold mashed beans dug out of the forty-nine-cent can. Unrefriger- ated _tortillas.__ Orange soda. That oom-pah music with the accordions and the tinny harmonies. But what was he doing on Topanga Canyon Boulevard at one-thirty in the afternoon, out there in the middle of nowhere? Working? Taking a lunch break?

And then all at once Delaney knew, and the understanding hit him with a jolt: the shopping cart, the _tortillas,__ the trail beaten into the dirt--he was camping down there, that's what he was doing. Camping. Living. Dwelling. Making the trees and bushes and the natural habitat of Topanga State Park into his own private domicile, crapping in the chaparral, dumping his trash behind rocks, polluting the stream and ru? I Aream andining it for everyone else. That was state property down there, rescued from the developers and their bulldozers and set aside for the use of the public, for nature, not for some outdoor ghetto. And what about fire danger? The canyon was a tinderbox this time of year, everyone knew that.

Delaney felt his guilt turn to anger, to outrage.

God, how he hated that sort of thing--the litter alone was enough to set him off. How many times had he gone down one trail or another with a group of volunteers, with the rakes and shovels and black plastic bags? And how many times had he come back, sometimes just days later, to find the whole thing trashed again? There wasn't a trail in the Santa

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher