![The Treason of the Ghosts]()

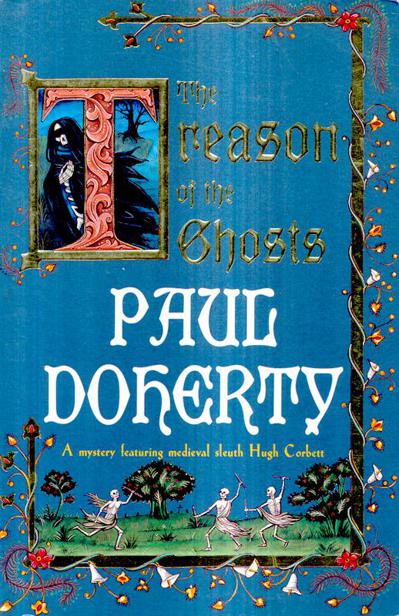

The Treason of the Ghosts

bailiffs.

Blidscote

took a step forward but the razor-sharp steel nicked his neck.

‘The

Golden Fleece will wait,’ the voice whispered. ‘I was telling you about the

penalty for treason and perjury. You will be taken to London and lodged in Newgate. Then you’ll be

fastened to a hurdle behind a horse and dragged all the way to Smithfield . They’ll put you up a ladder and

turn you off. Your fat legs will dance, your face will

go black as your tongue protrudes. Afterwards they’ll cut you down, half dead

or half alive. Does it really matter? They’ll quarter your sorry trunk, pickle

it; dip it in tar, fix it above the city gates. Ah, travellers will comment,

there’s Master Blidscote!’

‘I

hear what you say,’ Blidscote gasped. ‘I have told you. I keep a still tongue

in my head and will do so till the day I die.’

‘I

like that, Master Blidscote. So, tell me now, Molkyn’s death and that of

Thorkle...?’

‘I

know nothing. I tell you, I know nothing. If I did—’

‘If

you do, Master Blidscote, I’ll come back and have more words with you. Now,

look at the wall. Go on, turn, look at the wall!’

Blidscote

obeyed.

‘Press

your face against it,’ the voice urged, ‘till you can smell the piss and count

to ten five times!’

Blidscote

stood for what appeared to be an age. When he turned, the shadows were empty. A

light to the mouth of the alleyway beckoned him forward. Blidscote shook off

the horrors of the night and ran. He reached the market square, the cobbles

glistening in the wetness of the night. The place was quiet. The houses and

shops beyond had their doors and windows closed but lights and lanterns glowed,

welcome relief to the darkness and cold. Blidscote realised he had lost his

staff. He ran back down the alleyway, collected it and returned to the

marketplace. The shock of the meeting with that demon had sobered him. He

adjusted his jerkin, pulling the cloak around his shoulders, and strode

purposefully across the marketplace. He stopped at the stocks where Peddlicott

the pickpocket had his head and hands tightly fastened in the pillory:

sentenced to stand there till dawn.

Peddlicott

lifted his head. ‘Master bailiff , of your charity?’

Blidscote

slapped him viciously on the cheek and walked towards the glowing warmth of the

Golden Fleece.

Ranulf-atte-Newgate,

together with Chanson, sat in the comfortable house of Master John Samler,

which stood in a lane on the edges of Melford. Ranulf stared around. The rushes

on the floor were clean and mixed with herbs. The plaster walls were freshly

washed with lime to keep away the flies, and decorated with coloured cloths.

Onions and a flitch of ham hung from the central beam to be cured in the

curling smoke from the fire in the open hearth. Chanson sat on the bench next

to Ranulf, hungrily eating the bowl of meat stew garnished with spice to liven

its dull taste. Ranulf picked up a piece of bread, smiled at his host and

dipped the bread into the bowl.

‘So,

John, you are a thatcher by trade?’

His

host, sitting opposite, eyes rounded at having such an important person talking

to him, nodded. Beside him, his wife, pink-cheeked with

excitement. Their children, supervised by their eldest girl, clustered

on the stairs. They reminded Ranulf of a group of owls, white-faced,

round-eyed. Ranulf felt uneasy. The thatcher was a prosperous man with a garden

plot before and a small orchard behind the house. He had been so overcome when

Ranulf knocked on the door, ushering him in as if he was the King himself,

serving the best ale his wife had brewed.

‘You

have five children, Master Samler?’

‘Eight

in all, two died...’ The thatcher’s voice trailed away.

‘And Johanna?’ Ranulf insisted. He looked across at the children.

‘Yes,

Johanna.’

‘I

understand,’ Ranulf continued softly, ‘that Elizabeth Wheelwright was murdered

a few days ago and your daughter Johanna earlier in the summer. Am I correct?’

Samler’s

wife began to sob. Chanson stopped eating and put down his horn spoon as a sign

of respect.

‘She

was a fine girl,’ Master Samler replied. ‘She wasn’t flighty in her ways.’

‘And

the day she died?’ Ranulf asked.

‘I

was out working. Johanna was sent on an errand. She loved the chance of going

into the market square to talk to her friends.’ He shrugged. ‘She went but

never came back.’

‘Was

there anyone special?’ Ranulf insisted. ‘Anyone at all?’ He lifted his head.

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher