![The Treason of the Ghosts]()

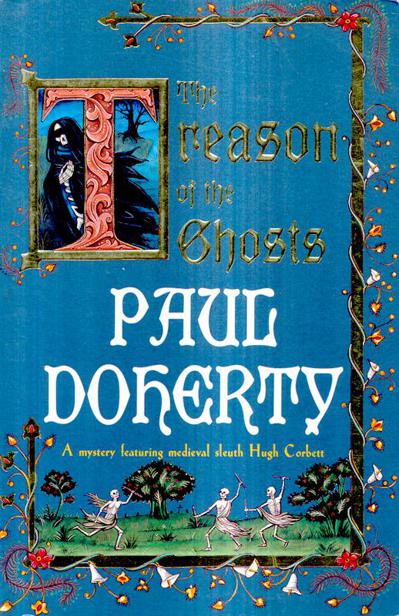

The Treason of the Ghosts

the moorlands or even in someone’s garden.

Melford is a prosperous place,’ he continued. ‘Think of the young girls from Norwich and Ipswich , the

Moon People and the travellers. A woman sickens and dies of the fever or, frail

with age, suffers an accident. What do these people do? They leave the

trackway. They don’t go very far but dig a shallow grave, place the woman’s

corpse there in some lonely copse or wood. A skeleton does not mean a murder,’

he concluded. ‘We don’t even know when this poor woman died. Do you still have

the ring?’

She

shook her head. ‘I traded it with a pedlar for needles and thread.’

Corbett

examined the bracelet. ‘It’s certainly copper, the

damp earth has turned it green.’ He held it up against the flame. ‘But I would

say...’

‘What,

clerk?’

Corbett

took out his dagger and tapped it against the bracelet.

‘It’s

not pure copper,’ he confirmed. ‘But some cheap tawdry

ornament. The same probably goes for the clothes and the girdle.’

He

crouched down beside the skeleton and examined it carefully. Sorrel was

correct. None of the ribs was broken, nor could Corbett detect any fracture of

the skull, arms or legs. He examined the chest, the line of the spine: no mark

or contusion.

‘The

effects of the garrotte string,’ he murmured, ‘would disappear with decay. How

many more of these graves did you say?’

‘Two

more and the bodies are no less decayed than this.’

Corbett,

mystified, replaced the bracelet. He rearranged the bones back on to the board,

covered them with the cloth and slid them back into the recess. Sorrel replaced

the bricks; Corbett helped her. He tried to recall his conversations with his

friend, a physician at St Bartholomew’s Hospital in London .

‘You

found no string? Nothing round the throat?’ he asked.

‘No,

I didn’t.’

Corbett

was about to continue his questioning when he heard a sound. He got to his feet

and moved to the window.

‘You

have sharp ears, clerk.’ Sorrel remained composed.

‘I thought

I heard a horse or pony, a rider...’

‘I

told you, someone I wished you to meet,’ she explained.

Corbett,

one hand on his dagger, stood by the window. He heard the jingle of a harness.

Whoever had arrived had already crossed the bridge. An owl hooted but the sound

came from below. Sorrel went to the window and imitated the same call. She

grasped Corbett’s hand.

‘Our

visitor has arrived.’

‘The Moon People?’

‘They

got tired of waiting,’ Sorrel explained. ‘They watch the hours as regularly as

a monk does his office.’

Corbett

stared up at the night sky. Aye, he reflected, and I watch mine. What time was

it? He had left the church with Sir Louis and Sir Maurice about an hour before

nightfall. It must be at least, he reckoned, three hours before midnight and he

still had other business to do: Molkyn’s widow to speak to for a start! He

heard a sound. Sorrel, holding the sconce torch, was standing in the doorway.

‘Come

on!’ she urged.

They

reached the cobbled yard. Sorrel’s visitor was standing in the middle. Corbett

made out his shadowy outline.

‘I

stood here deliberately.’ The voice had a strong country burr. Corbett

recognised the tongue of the south-west. ‘I didn’t want to startle you.’

The

man stepped into the pool of light. He was tall. Raven-black hair, parted down

the middle, fell to his shoulders; sharp eyes like a bird, crooked nose, his

mouth and chin hidden by a black bushy moustache and beard. He was

swarthy-skinned and Corbett glimpsed the silver earrings in each earlobe. He

smelt of wood smoke and tanned leather. The stranger was dressed from head to

toe in animal skins: the jacket sleeves were of leather, the front being of

mole’s fur, with leggings of tanned deerskin pushed into sturdy black boots. He

wore a war belt which carried a stabbing dirk and a dagger. Bracelets winked at

his wrists, rings on his fingers.

The

stranger studied Corbett from head to toe. ‘So, you’re the King’s clerk?’

‘You

should have waited,’ Sorrel accused. ‘I would have brought him.’

The

man’s gaze held Corbett’s.

‘I

did not want to meet him,’ he replied insolently. ‘I don’t like King’s

officers, I don’t like clerks. I only said I would see him because you asked.

What I’ve got to say isn’t much. You said you’d bring him to see me if you

could.’

Corbett

glanced at Sorrel and smiled. He was intrigued by how much this woman

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher