![The Twisted Root]()

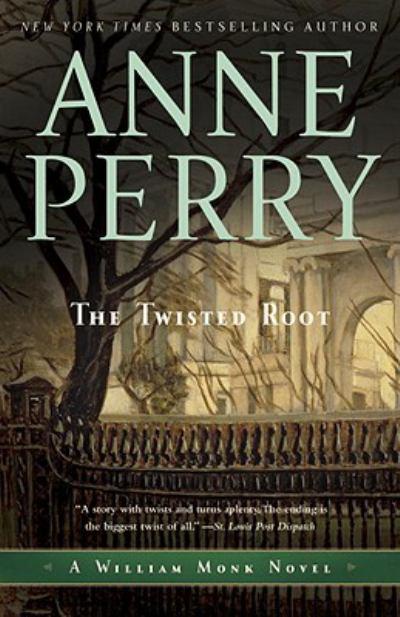

The Twisted Root

unquestionably be death. Rathbone had a justifiably high opinion of his own abilities, but the obstacles in this case seemed insuperable. It was extremely foolish to have such a will to win. In fact, it was a classic example of a man’s allowing his emotions not merely to eliminate his judgment but to sweep it away entirely.

He called his clerk in and enquired about his appointments for the next two days. There was nothing which could not be either postponed or dealt with by someone else. He duly requested that that be done, and left for his home, his mind absorbed in the issue of Cleo Anderson, Miriam Gardiner and the crimes with which they were charged.

In the morning, he presented himself at the Hampstead police station. He informed them that he was the barrister retained by Cleo Anderson’s solicitor and that he wished to speak with her without delay.

"Sir Oliver Rathbone?" the desk sergeant said with amazement, looking at the card Rathbone had given him.

Rathbone did not bother to reply.

The sergeant cleared his throat. "Yes sir. If you’ll come this way, I’ll take yer ter the cells ... sir." He was still shaking his head as he led the way back through the narrow passage and down the steps, and finally to the iron door with its huge lock. The key squeaked in the lock as he turned it and swung the door open.

" ’Ere’s yer lawyer ter see yer," he said, the lift of disbelief in his voice.

Rathbone thanked him and waited until he had closed the door and gone.

Cleo Anderson was a handsome woman with fine eyes and strong, gentle features, but at the moment she was so weary and ravaged by grief that her skin looked gray and the lines of her face dragged downwards. She regarded Rathbone without comprehension and—what worried him more—without interest.

"My name is Oliver Rathbone," he introduced himself. "I have come to see if I can be of assistance to you in your present difficulty. Anything you say to me is completely confidential, but you must tell me the truth or I cannot be of any use." He saw the beginning of denial in her face. He sat down on the one hard chair, opposite where she was sitting on the cot. "I have been retained by Miss Hester Latterly." Too late he realized he should have said "Mrs. Monk." He felt the heat in his face as he was obliged to correct himself.

"She shouldn’t have," Cleo said sadly, her face pinched, emotion raw in her voice. "She’s a good woman, but she doesn’t have money to spend on the likes o’ you. I’m sorry for your trouble, but there’s no job for you here."

He was prepared for her answer.

"She told me that you took certain medicines from the hospital and gave them to patients who you knew were in need of them but were unable to pay."

Cleo stared at him.

He had not expected a confession. "If that were so, it would be theft, of course, and illegal," he continued. "But it would be an act which many people would admire, perhaps even wish that they had had the courage to perform themselves."

"Maybe," she agreed with a tiny smile. "But it’s still theft, like you said. Do you want me to admit it? Would it help Miriam if I did?"

"That was not my purpose in discussing it, Mrs. Anderson." He held her gaze steadily. "But a person who would do such a thing obviously placed the welfare of other people before her own. As far as I can see, it was an act, a series of acts, for which she expected no profit other than that of having done what she believed to be right and of benefit to others for whose welfare she cared. Possibly she believed in a cause."

She frowned. "Why are you saying all this? You’re talking about ’ifs’ and ’maybes.’ What do you want?"

He smiled in spite of himself. "That you should accept that occasionally people do things without expecting to be paid, because they care. Not only people like you—sometimes people like me, too."

A flush of embarrassment spread up her cheeks, and the line of her mouth softened. "I’m sorry, Mr. Rathbone, I didn’t mean to insult you. But with the best will in the world, you can’t clear me of thieving those medicines, unless you find a way to blame some other poor soul who’s innocent—and if you did that, how would I go to m y Maker in peace?"

"That’s not how I work, Mrs. Anderson." He did not bother to correct her as to his title. It seemed remarkably unimportant now. "If you took the medicines, I have two options: either to plead mitigating circumstances and hope that they will

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher