![The Twisted Root]()

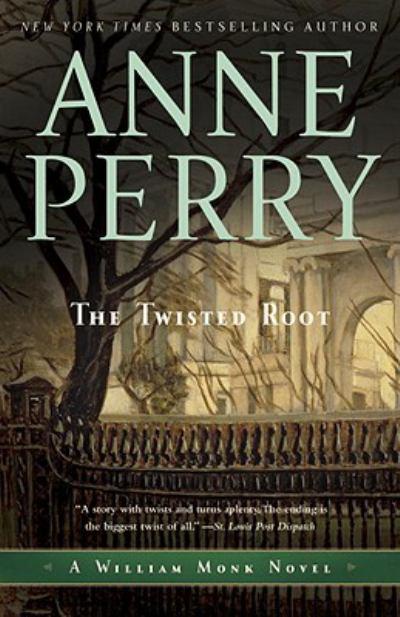

The Twisted Root

herself, or to sell, but to give to the old and poor that she visits, who are in desperate need, many of them dying."

"Laudable but illegal," Rathbone said with a frown. His interest was already caught, and his concern.

"Precisely," Monk agreed. "Somehow a coachman named James Treadwell learned of her thefts and was blackmailing her. How he learned is immaterial. He comes from an area close by, and possibly he knew someone she was caring for. He was found dead on the path close to her doorway. She has been charged with his murder."

"Physical evidence?" Rathbone said with pressed lips, his face already darker, brows drawn down.

"None, all on motive and opportunity. The weapon has not been found. But that is not all...."

Rathbone’s eyes widened incredulously. "There’s more?"

"And worse," Monk replied. "Some twenty years ago Mrs. Anderson found in acute distress a girl of about twelve or thirteen years old. She took her in and treated her as her own." He saw Rathbone’s guarded expression, and the further spark of interest in his eyes. "Miriam grew up and married comfortably," Monk continued. "She was widowed, and then fell deeply in love with a young man, Lucius Stourbridge, of wealthy and respectable family, who more than returned her feelings. They became engaged to marry with his parents’ approval. Then one day, for no known reason, she fled, with the said coachman, back to Hampstead Heath."

"The night of his death, I presume," Rathbone said with a twisted smile.

"Just so," Monk agreed. "At first she was charged with his murder and would say nothing of her flight, its reason, or what happened, except to deny that she killed him."

"And she wasn’t charged?" Rathbone was surprised.

"Yes, she was. Then when a far better motive was found for the nurse, she was released."

"And the worse that you have to add?" Rathbone asked.

Monk’s shoulders stiffened. "Last night I had a message from the young policeman on the case—incidentally, his grandfather is one of those for whom the nurse stole medicines—to ask me to go to the family home in Cleveland Square, where the mother of the young man had just been found murdered ... in what seems to be exactly the same manner as the coachman on Hampstead Heath."

Rathbone shut his eyes and let out a long, slow breath. "I hope that is now all?"

"Not quite," Monk replied. "They have arrested Miriam and charged her with the murder of Stourbrldge’s mother, and Miriam and Cleo as being accomplices in murder for gain. There is considerable money in the family, and lands."

Rathbone opened his eyes and stared at Monk. "Have you completed this tale to date?"

"Yes."

Hester spoke for the first time, leaning forward a little, her voice urgent. "Please help, Oliver. I know Miriam may be beyond anything anybody can do, except perhaps plead that she may be mad, but Cleo Anderson is a good woman. She took medicine to treat the old and ill who have barely enough money to survive. John Robb, the policeman’s grandfather, fought at Trafalgar—on the Victory! He, and men like him, don’t deserve to be left to die in pain that we could alleviate! We asked everything of them when we were in danger. When we thought Napoleon was going to invade and conquer us, we expected them to fight and die for us, or to lose arms or legs or eyes..."

"I know!" Rathbone held up his slender hand. "1 know, my dear. You do not need to persuade me. And a jury might well be moved by such things, but a judge will not. He won’t ask them to decide whether a blackmailer is of more or less value than a nurse, or an old soldier, simply did she kill him or not. And what about this other woman, the younger one? What possible reason or excuse did she have for murdering her prospective mother-in-law?"

"We don’t know," Hester said helplessly. "She won’t say anything."

"Is she aware of her position, that if she is found guilty she will hang?"

"She knows the words," Monk replied. "Whether she comprehends their meaning or not I am uncertain. I was there when she was arrested, and she seemed numb, but she left with the police with more dignity than I have seen in anyone else I can recall." He felt foolish as he said it. It was an emotional response, and he disliked having Rathbone see him in such a light. It made him vulnerable. He was about to add something to qualify it, defend himself, but Rathbone had turned to Hester and was not listening.

"Do you know this nurse?" he asked.

"Yes," she said

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher