![Three Seconds]()

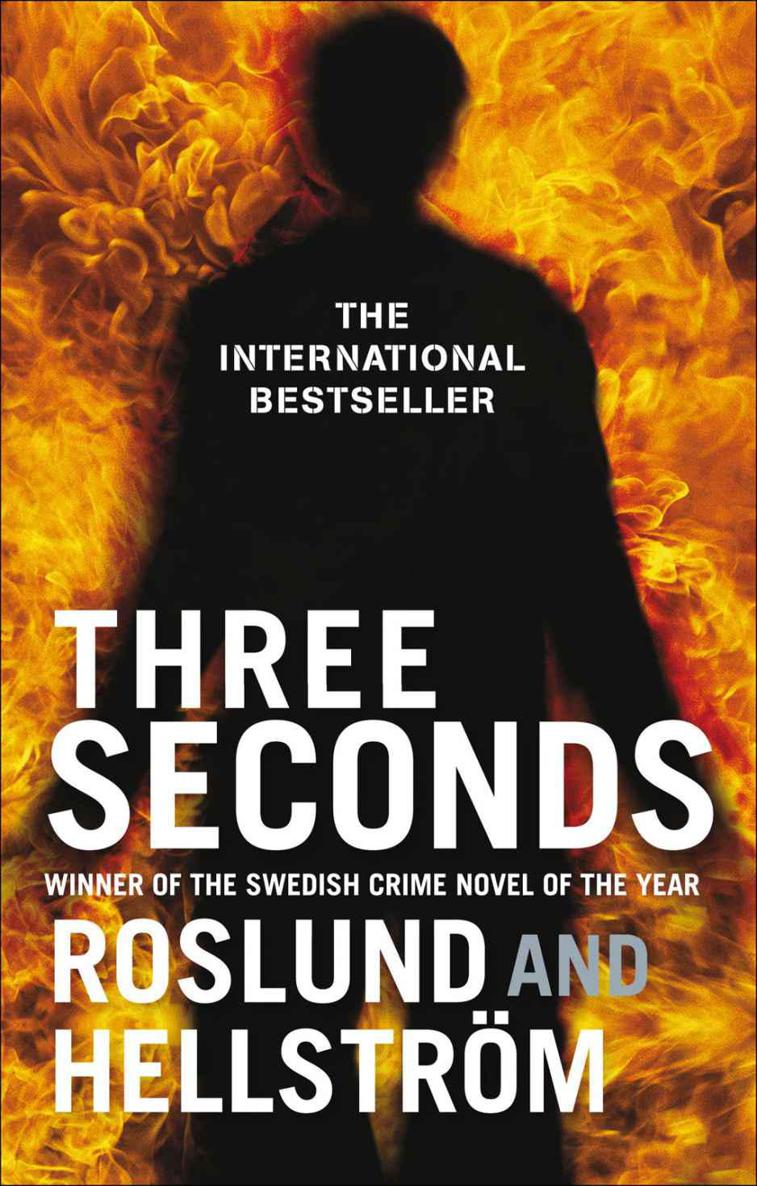

Three Seconds

Daddy.’

‘Hello-lello, Daddy.’

‘Hello-lello-lello, Daddy.’

‘Hello-lello-lello—’

‘Hello, you two. You both win. We haven’t got time for any more hellos today. Maybe tomorrow. Then there will be more time. OK?’

He reached out for the red jacket and pulled it on to Rasmus’s outstretched arms, then sat him on his lap to take his indoor shoes off the feet that wouldn’t keep still, and put on his outdoor shoes. He leant forwards and glanced at his own shoes. Shit. He’d forgotten to putthem in the fire. The black shininess might be a film of death, with traces of skin and blood and brain tissue – he had to burn them as soon as he got home.

He checked the child car seat that was strapped onto the passenger seat, facing backwards. It felt as secure as it should and Rasmus was already picking at the pattern on the fabric as was his wont. Hugo’s seat was more like a hard square that made him sit a bit higher and he fastened the seat belt tight before giving his soft cheek a quick kiss.

‘Daddy’s just going to make a quick phone call. Will you be quiet for a while? I promise to be finished before we drive under Nynäsvägen.’

Capsules with amphetamine, child car seats secured, shoes shiny with the remains of death.

Right now he didn’t want to see that they were different parts of the same working day.

He closed his phone the moment the car passed the busy main road. He had managed to make two quick calls, the first to a travel agent to book a ticket on the 18.55 SAS flight to Warsaw, and the second to Henryk, his contact at head office, to book a meeting there three hours later.

‘I did it! I finished on this side of the road. Now I’m only going to talk to you.’

‘Were you talking to work?’

‘Yes, the office.’

Three years old. And he could already distinguish between the two languages and what Daddy used them for. He stroked Rasmus’s hair and felt Hugo leaning forwards to say something behind him.

‘I can speak Polish too.

Jeden, dwa, trzy, cztery, pi ę ć , sze ś ć , siedem

—’

He stopped, and then carried on in a slightly darker voice: ‘—eight, nine, ten.’

‘Very good. You know lots of numbers.’

‘I want to know more.’

‘

Osiem, dziewi ę ć , dziesi ę ć

.’

‘

Osiem, dziewi ę ć

…

dziesi ę ć

?’

‘Now you know them.’

‘Now I know.’

They drove past the Enskede flower shop and Piet Hoffmann stopped, reversed and got out.

‘Wait here. I’ll be back in a moment.’

A couple of hundred metres further on, a small red plastic fire engine was standing in front of the garage and he just managed to avoid it, but only by scraping the right-hand side of the car against the fence. He released the seat belts and child car seats and watched their feet run over the moss green grass. They both threw themselves down on to the ground and crawled through the low hedge into the neighbour’s garden, where there were three children and two dogs. Piet Hoffmann laughed and felt a warmth in his belly and throat, their energy and joy, sometimes things were just so simple.

He held the flowers in one hand as he opened the door to the house that they had left in such a rush – it had been one of those mornings when everything took a little bit longer. He would tidy away the breakfast dishes that were still on the table, and pick up the trail of clothes that spread through every room downstairs, but first he had to go down into the cellar and the boiler room.

It was May and the timer on the boiler would be turned off for a long time yet, so he started it manually by pressing the red button, then he opened the door and listened to it cranking into action and starting to burn. He bent down, undid his shoes and dropped them into the flames.

The three red roses would go on the middle of the kitchen table in the vase that he liked so much, the one they’d bought at the Kosta Boda glassworks one summer. Plates for Zofia, Hugo and Rasmus in the places where they had sat every day since they left the flat the same summer. Half a kilo of defrosted mince from the top shelf in the fridge which he browned in the frying pan, salt and pepper, single cream and two tins of chopped tomatoes. It was starting to smell good, a finger in the sauce – it tasted good too. A half-full pan of water and a bit of olive oil so that the pasta wouldn’t boil over.

He went upstairs to the bedroom. The bed was still unmade and he buried his face in the pillow that

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher