![Three Seconds]()

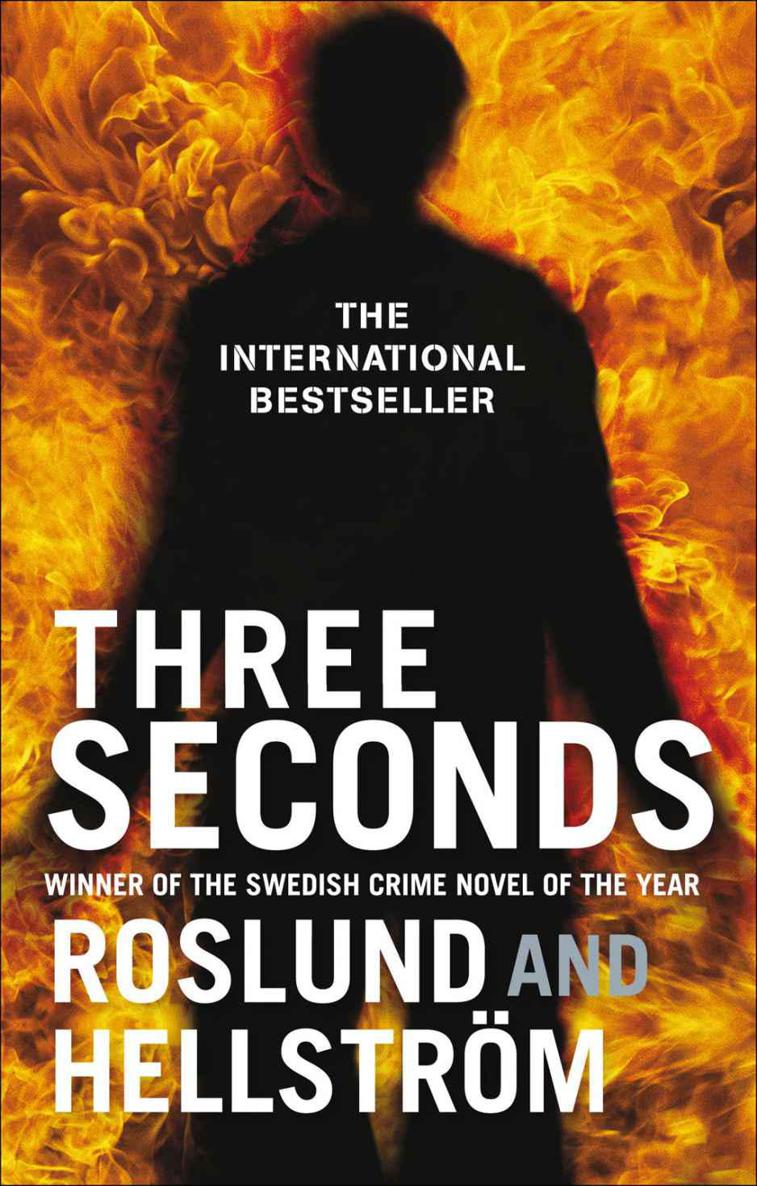

Three Seconds

An hour to midnight.

It was late spring, but darker than he thought it would be. Probably because of the water down below, almost black, a membrane covering what seemed to be bottomless.

He didn’t like boats, or perhaps it was the sea he couldn’t fathom. He always shivered when the wind blew as it did now and Ś winouj ś cie slowly disappeared. He would stand with his hands gripped tightly round the handrail until the houses were no longer houses, just small squares that disintegrated into the darkness that grew around him.

He was twenty-nine years old and frightened.

He heard people moving around behind him, on their way somewhere, too; just one night and a few hours’ sleep, then they would wake in another country.

He leant forward and closed his eyes. Each journey seemed to be worse than the last, his mind and heart as aware of the risk as his body; shaking hands, sweating brow and burning cheeks, despite the fact that he was actually freezing in the cutting, bitter wind. Two days. In two days he’d be standing here again, on his way back, and he would already have forgotten that he’d sworn never to do it again.

He let go of the railing and opened the door that swapped the cold for warmth and led onto one of the main staircases where unknown faces moved towards their cabins.

He didn’t want to sleep, he couldn’t sleep – not yet.

There wasn’t much of a bar. M/S

Wawel

was one of the biggest ferries between northern Poland and southern Sweden, but all the same; tables with crumbs on, and chairs with such flimsy backs that it was obvious you weren’t supposed to sit there for long.

He was still sweating. Staring straight ahead, his hands chased the sandwich round the plate and lunged for the glass of beer, trying not to let his fear show. A couple of swigs of beer, some cheese – he still felt sick and hoped that the new tastes would overwhelm the others: the big, fatty piece of pork he’d been forced to eat until his stomach wassoft and ready, then the yellow stuff concealed in brown rubber. They counted each time he swallowed, two hundred times, until the rubber balls had shredded his throat.

‘

Czy poda ć panu co ś jeszcze?

’

The young waitress looked at him. He shook his head, not tonight, nothing more.

His burning cheeks were now numb. He looked at the pale face in the mirror beside the till as he nudged the untouched sandwich and full glass of beer as far down the bar as he could. He pointed at them until the waitress understood and moved them to the dirty dishes shelf.

‘

Postawi ć ci piwo?

’ A man his own age, slightly drunk, the kind who just wants to talk to someone, doesn’t matter who, to avoid being alone. He kept staring straight ahead at the white face in the mirror, didn’t even turn round. It was hard to know for sure who was asking and why. Someone sitting nearby pretending to be drunk, who offered him a drink, might also be someone who knew the reason for his journey. He put twenty euros down on the silver plate with the bill and left the deserted room with its empty tables and meaningless music.

He wanted to scream with thirst and his tongue searched for some saliva to ease the dryness. He didn’t dare drink anything, too frightened of being sick, of not being able to keep down everything that he’d swallowed.

He had to do it, keep it all down, or else – he knew the way things worked – he was a dead man.

He listened to the birds, as he often did in the late afternoon when the warm air that came from somewhere in the Atlantic retreated reluctantly in advance of another cool spring evening. It was the time of day he liked best, when he had finished what he had to do and was anything but tired and so had a good few hours before he would have to lie down on the narrow hotel bed and try to sleep in the room that was still only filled with loneliness.

Erik Wilson felt the chill brush his face, and for a brief moment closed his eyes against the strong floodlights that drenched everything in a glare that was too white. He tilted his head back and peered warily up at the great knots of sharp barbed wire that made the high fence even higher, and had to fight the bizarre feeling that they were toppling towards him.

From a few hundred metres away, the sound of a group of people moving across the vast floodlit area of hard asphalt.

A line of men dressed in black, six across, with a seventh behind.

An equally black vehicle shadowed them.

Wilson

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher