![Three Seconds]()

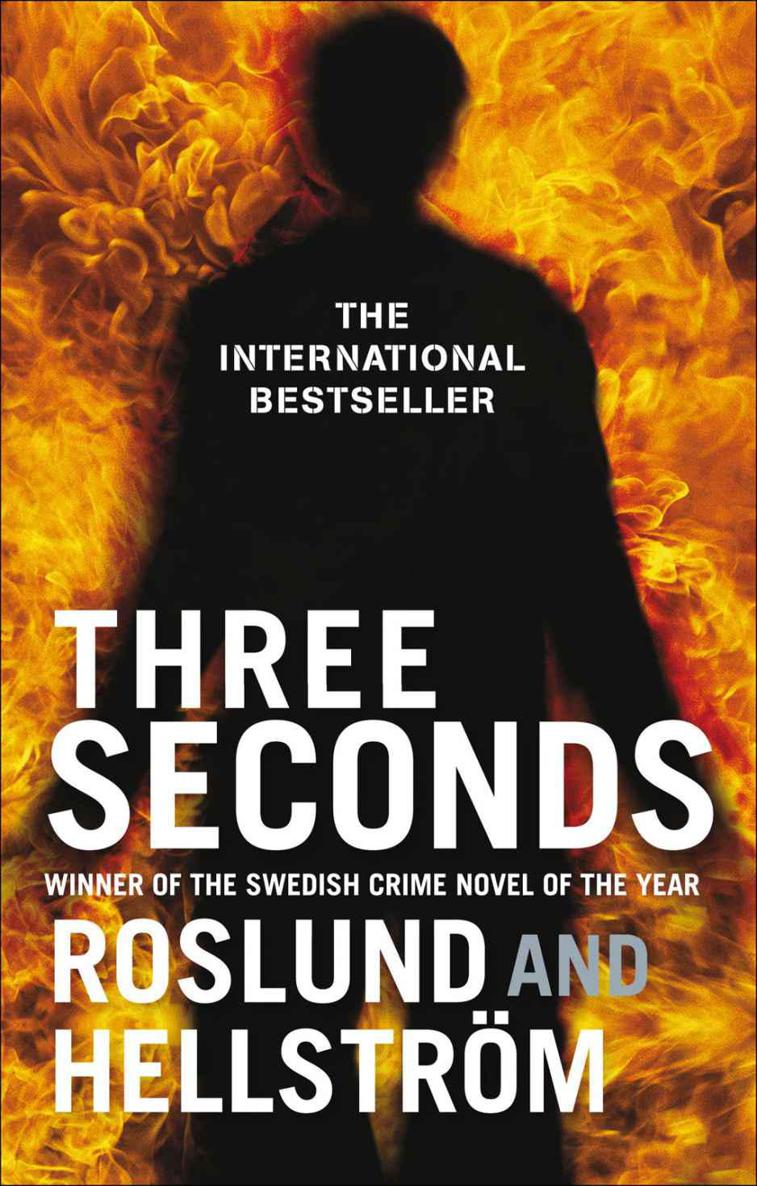

Three Seconds

Simrishamn in Sweden.

Right onto ul. Ludwika Idzikowskiego, quarter of an hour to go.

In the past few years he had visited this country, which belonged to him, so many times. He could have been born here, grown up here and then he would have been very different, like the people in Bortoszyce who had tried to keep in touch for so long after his mother and father died, and who had eventually given up when he gave nothing back. Why had he done that? He didn’t know. Nor did he know why he never got in touch when he was nearby, why he had never gone to visit.

‘Sixty zloty. Forty for the journey and twenty for that bloody stop that we hadn’t agreed on.’

Hoffmann left a hundred-zloty note on the seat and got out of the car.

A big, dark, old building in the middle of Mokotów – as old as a building could be in Warsaw, which had been totally destroyed seventy years ago. Henryk was waiting for him on the steps outside. Theyshook hands but didn’t say much; neither of them knew how to do small talk.

The meeting room was at the end of a corridor on the tenth floor. Far too light and far too warm. The Deputy CEO and a man in his sixties, who he assumed was the Roof, were waiting at the end of the oblong table. Piet Hoffmann accepted their unnecessarily firm handshakes and then went to sit down on the chair that had already been pulled out. There was a bottle of water on the table in front of it.

He didn’t shy away from their piercing eyes. If he had done that, chosen to retreat, it would be over already.

Zbigniew Boruc and Grzegorz Krzynówek.

He still didn’t know. If they were sitting there because he was going to die. Or because he had just penetrated further.

‘Mr Krzynówek will just sit and listen. I assume that you haven’t met before?’

Hoffmann nodded to the elegant suit.

‘We haven’t met, but I know who you are.’

He smiled at the man whom he had seen over the years in Polish newspapers and on Polish television, a businessman whose name he had also heard whispered in the long corridors at Wojtek, which had emerged from precisely the same chaos as every other new organisation in an Eastern European state; a wall had suddenly fallen and economic and criminal interests merged in a grab and scramble for capital. Organisations that were established by the military and police and that all had the same hierarchical structure, with the Roof on top. Grzegorz Krzynówek was Wojtek’s Roof and he was perfect. A champion with a central position, extremely robust financially and unassailable in a society that required laws, a guarantee that combined finance and criminality, a facade for capital and violence.

‘The delivery?’

The Deputy CEO had studied him long enough.

‘Yes.’

‘I assume that it’s safe.’

‘It’s safe.’

‘We’ll check it.’

‘It will still be safe.’

‘Let’s continue then.’

That was all. That was yesterday.

Piet Hoffmann wasn’t going to die this evening.

He wanted to laugh – as the tension vanished something else bubbled up and longed to escape, but there was more to come. No threats, no danger, but more ritual that required continued dignity.

‘I don’t appreciate the condition you left our flat in.’

First he made sure that the delivery was safe. Then he asked about the dead man. The Deputy CEO’s voice was calmer, friendlier now that he was talking about something that wasn’t as important.

‘I don’t want my people here to have to explain to the Polish police, on the request of the Swedish police, why and how they rent flats in central Stockholm.’

Piet Hoffmann knew that he had to answer this question too. But he took his time, looked over at Krzynówek.

Delivery. I don’t appreciate the condition you left our flat in.

The respected businessman knew exactly what they were talking about. But words are strange like that. If they’re not used officially, they don’t exist. No one here in this room would mention twenty-seven kilos of amphetamine and a killing. Not so long as a person who officially didn’t know anything about it was sitting in their midst.

‘If the agreement that I, and only

I

, have the authority to lead an operation in Sweden had been respected, this would never have happened.’

‘I’d like you to explain.’

‘If your people had followed your instructions instead of using their own initiative, the situation would never have arisen.’

Operation. Own initiative. The situation.

Hoffmann looked at the

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher