![Tied With a Bow]()

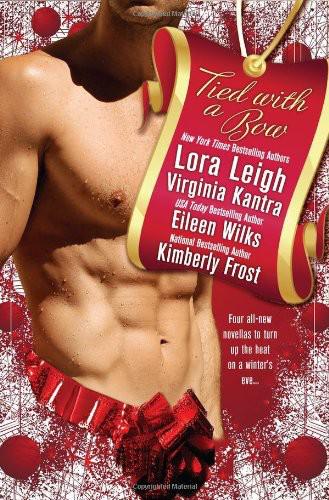

Tied With a Bow

her rounded chin. “Then we will not go.”

“My dear . . .” The comtesse coughed. “You have no choice.”

“I won’t leave you.” The girl’s voice rose, provoking glances and whispers from her fellow prisoners.

But the cell’s other inhabitants were too respectful of her grief, too fearful of fever or sunk in their own despair to intervene.

“I cannot remove her against her will,” the angel said.

“You promised to save her,” Solange said.

Irritation flickered through him, crackled like ozone in the air. Frustration with her, with himself, with the sins of men and the limitations of angels. “She does not wish to be rescued.”

Intervention was one thing. He might be forgiven for granting a dying mother’s prayer. But violating a human being’s free will was another, far more serious offense.

He looked at the girl, her springy dark curls, her clear, wide eyes, the jut of that childlike chin. She was old enough to make her own decisions.

His chest tightened. And far too young to die. Her goodness shone in this mortal Hell like a star.

Solange continued as if he had not spoken. “I have family in England. A cousin.” Her voice, her strength, flared and faded like a sullen fire. “Héloïse married an Englishman. Basing. Sir Walter Basing. You will . . . take my Aimée to them?”

“No,” the girl said fiercely. Her cheeks were flushed, her shoulders rigid. “It is my life. My choice.”

Stubborn. He would need to silence her to get her past the prison guards.

He did not look forward to taking solid form, to descending into the flesh and the stink and the pain of human existence to lug her through the barricades. He dare not save them all.

But the girl would live. She would be safe in England. He would be damned before he’d let this child’s light be extinguished.

His lip curled. He might be damned, anyway.

He breathed on the girl, catching her slight body as she slumped.

They didn’t have much time.

The straw rustled and prickled. Pailleux , the guards called the poorest prisoners, after the paille , hay, they slept on.

Aimée squeezed her eyes shut, burrowing back to sleep, reluctant to exchange the comfort of her dreams for vermin-infested straw. Soft, dark, velvet dreams of being carried in hard, strong arms while the stars wheeled and pulsed overhead. Dreams of being safe, protected, warm.

Hay tickled her arms, poked through the shabby protection of her shawl. She sighed. It was no use. She lay still, waiting for the stench of the prison to assail her nostrils, but she smelled only sweet cut grass and the richness of cows. Earthy smells, homey smells, like the stables of Brissac.

She frowned and opened her eyes.

A man stood in the window of the hayloft. Her heart bumped. A very large man, his broad shoulders made broader by a cape, silhouetted against the starry sky. His profile was silver, outlined by the moon.

Except . . . Her gaze slid past him to the spangled sky. There was no moon.

Fear skittered inside her like a rat. “Where am I?”

He turned at once at the sound of her voice. She could not see his expression, only the bulk of him against the sky, but she remembered his face, beautifully severe in the darkness of the dungeon. “Do not be afraid. You are safe now.”

Which was no answer at all.

Her head felt stuffed with rags, her chest hollow. She raised herself cautiously on the straw.

“Maman?” Her voice cracked shamefully on the word.

Silence.

“Your mother entrusted you to my care,” he said at last.

Which meant . . .

Which could only mean . . .

Her mind splintered, and her heart, shattering like a thin sheet of ice over a puddle, the bright shards of her former life melting into nothingness. Her body was cold, cold. Her throat burned. She swallowed, pulling her shawl tighter around her.

“I will see you reach your family,” he said.

Her family was dead. Maman was . . .

A scream built and built inside her head, a wild, discordant squawk of rage and grief like a peacock’s cry. She felt it swell her lungs, climb in her throat, press against her teeth. But all that emerged was a whisper. “ No . Take me back.”

He shook his head. “Too late for that. For both of us.”

Her lips were numb. “I do not understand.”

“The tide turns in a few hours. Our boat goes with it.”

“A boat,” she repeated. Her hands were shaking. She hid them in her shawl.

He nodded. “To England.”

Impossible. She was no student of

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher