![Up Till Now. The Autobiography]()

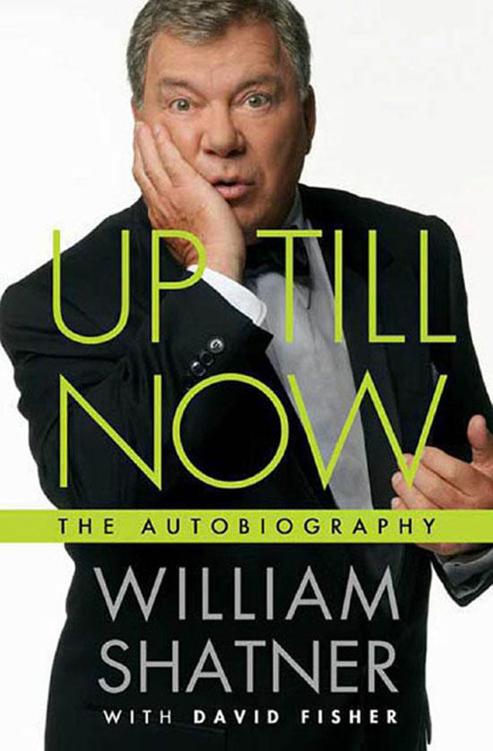

Up Till Now. The Autobiography

decision, Captain.

Perhaps more important, the people who wrote these letters suddenly had an emotional attachment to a television program unlike any viewers ever before. They had actually influenced a network’sprogramming decision. They had ownership; Star Trek really had become their show. This marked the beginning of the most unusual relationship between viewers and a TV series in history.

NBC scheduled the show for Monday nights at 7:30, the perfect time slot for us because our audience consisted primarily of teenagers, college students, and young adults, science-fiction fans who would be home at that hour. But when George Schlatter, the producer of NBC’s top-rated Laugh-In —which would have to be moved a half-hour from its 8 P.M. starting time—objected, the network moved us to Friday nights at 10 P.M.

It was no Bonanza —for Star Trek this was the worst possible time slot. No one in our universe was going to stay home Friday night to watch television. Our audience was out on Friday nights. Not home, no esta en la casa, gone, away. Those people who would be at home weren’t going to be watching science fiction. Even then NBC reduced our budget, paying $15,000 less per episode than it had during our first season. That meant that we could no longer film on location, we couldn’t pay guest stars, and one of every four shows had to be done entirely on the Enterprise.

Our first show that third season might have been a tribute to the NBC executives who so mishandled this show: it was about a society in desperate need of a brain. It was entitled “Spock’s Brain” and took place on Stardate 5431.4. I don’t know what day of the week that would have been—but I can assure you it was not a Friday night at ten o’clock. Because even aliens are busy Friday nights at ten o’clock. In this story a beautiful alien woman beams aboard the Enterprise and steals Spock’s brain, turning him into a zombie, and causing Bones to have to utter one of the worst lines of all seventy-nine episodes, “Jim. His brain is gone!” We had twenty-four hours to find Spock’s brain somewhere in the entire universe, then reinsert it in his head. Naturally Spock comes along with us, showing all the emotion of... Spock. Eventually we discover a race that needs his brain to control its planet’s life-supporting power systems. McCoy operates to reinsert Spock’s brain—during which Spock awakens and instructs him how the parts should be properly connected. Inthe dramatic highlight of the episode we are all standing by the operating table, waiting anxiously to see if Spock will survive this operation. Suddenly, Spock opens his eyes, looks at me and blinks several times, and then says in absolute astonishment, “Friday night at ten o’clock?”

Perhaps he didn’t. But it was true, of course. The show was canceled after three seasons on the air. In January 1969, we filmed the final episode. It had been a good job, a good cast, but it was over. During the three years I’d worked on the show my life had changed completely. Gloria and I had finally separated and, early one afternoon in 1967, as we were filming an episode called “Devil in the Dark,” I received a phone call telling me my father had died of a heart attack while playing golf in Florida.

There is no way to prepare for the death of a parent. It is a knot in time into which all the emotions you’ve ever felt about that relationship come racing together. It is the ultimate unfinished symphony, with the loose ends of life and loves to somehow be bound together. Well, all of that hit me—and I had work to do. We were in the middle of a scene and it had to be finished. I owed it to my fellow actors. The first plane to Florida didn’t leave for several hours, so rather than wait in an airport I decided to work, hoping the familiarity of my work would provide me with at least a few moments of peace.

Working that day was very difficult. I’d spent my career masking the reality of my own feelings, and instead presenting to the camera the emotional life of the character I was playing. As an actor you learn to do that, to blank out everything except the persona of the character you’re playing, and that’s what I tried to do because that’s what I had always done. I also knew that if I faltered it would be on camera as long as film lasted. Sooner or later the pain I was feeling would go away—but the impact of it on my performance would be recorded on film

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher