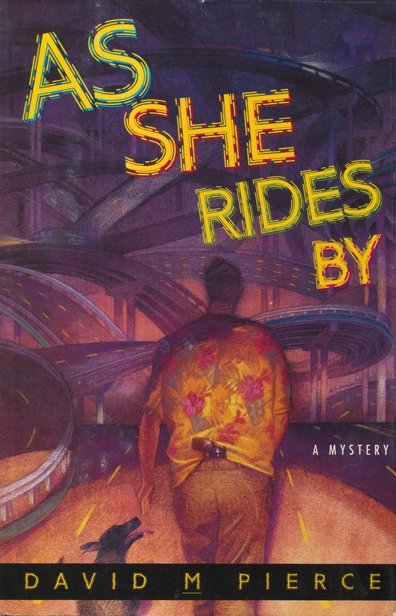

![Vic Daniel 6 - As she rides by]()

Vic Daniel 6 - As she rides by

on.” I hung on. He came about one last time, then ran us right up onto the sand, from which I deducted that his boat had neither a keel nor a centerboard.

“Never been so glad to see sand in my life,” I said, climbing out a touch shakily while Chris the girl pulled the surfboard in and then began untying my bag. I checked to see what time it was; both timepieces were still working, and both said it was one-thirty—I’d been out on that damn board almost two hours. Chris trotted over and handed me my bag. I unzipped it and was relieved to see no water had leaked in.

Then Christopher said, “Well, it’s been fun, like, but we should shove off, if you’re OK now, sir.”

“OK?” I said. “Kids, I’m over the moon. Hang on a sec.” I took off the Rolex and passed it to him. “A small, a miniscule gesture of my appreciation.” I rummaged around in the bag, came up with a memo pad and a felt-tip, wrote my name and phone number down, then passed that over. “In case you get any hassles from your folks, Chris, get one of them to call me and I’ll square it. As for you,” I said to Chris the girl, “you have just inherited this one-owner, low-sea mileage, surfboard, which I never want to see again in my life. Your protests availeth naught.” I shook hands with Christopher, kissed Chris in an avuncular fashion on one smooth, tanned, salty, cheek, hefted my bag, and headed off up Las Tunas Beach toward the nearest bar.

As it happened, I did get a call from Christopher’s mom, at my office, two days later. I reassured her that the watch was indeed a gift, that her son and Chris had probably saved my life, and said that she could rightly think very highly of him. There was a pause, then she laughed, and then she said, “Well, more highly than I did last Saturday, when I found a tobacco tin full of pot and a full bottle of his father’s Black Label hidden in his closet.”

“Kid stuff,” I scoffed, “and anyway, if he didn’t secretly want you to find them, he never would have hidden them there, it’s the first place a mom would look.” She laughed again, and in a roundabout way, inquired as to my occupation, viz., what did I do to get so rich I could give away Rollies and surfboards to teenage kids? I didn’t think I should bother mentioning it was easy, neither of them were mine, so I said instead something portentously enigmatic like, “You tell me the value of a secondhand watch plus a secondhand surfboard against that of a secondhand life,” which she no doubt thought was total hogwash but was charitable enough to accept.

Anyway. On the far side of the boardwalk I found a dimly lit, sawdust-smelling estaminet called Peggy’s Pub, into which I gratefully hastened.

“What ‘cha been doing, lofty, practicing drowning?” said the pretty barlady, taking in my generally water-logged appearance.

“Forget the practicing,” I said. “Actually”—and here I adopted a sheepish look—“I fell into the kids’ wading pool, would you believe it?”

“Not for a second,” she said. “You drinkin’?”

“Soon as you finish pouring,” I said. While she was concocting me a large brandy and ginger ale, I ducked into the men’s room, changed into dry clothes, wrung out the wet, wrapped them in the newspaper, retrieved my wallet, wiped the trickle of blood off my cheek, went back out, climbed aboard a stool at the long, wooden bar, silently toasted the Fates, and down around the hidden bend that first, delicious, swallow went. It was closely followed by a second, then a third. Shortly thereafter, the drink itself was followed by a second, then a third, the third one being accompanied by an invention that rivals even that of the wind—a chili dog, heavy on the onions and the grease: I started to feel like the old Vic Daniel once again, and the old Vic Daniel had things to do, so he better start doing them. I had to do something about the Mercedes, of course, and I had to do something about getting me back to civilization, or if not civilization, I’d settle for Beverly Hills . So I asked the pretty barlady if she could recommend a good local garage.

“Ask me a hard one,” she said, pouring out a banana daiquiri for a client with a flourish. The client didn’t have the flourish—but he did have a large badge that read, “I’m too young to be this old”—it was the pour that flourished. “He only works there, when he’s working,” she went on, pointing to a lanky type in

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher