![Waiting for Wednesday]()

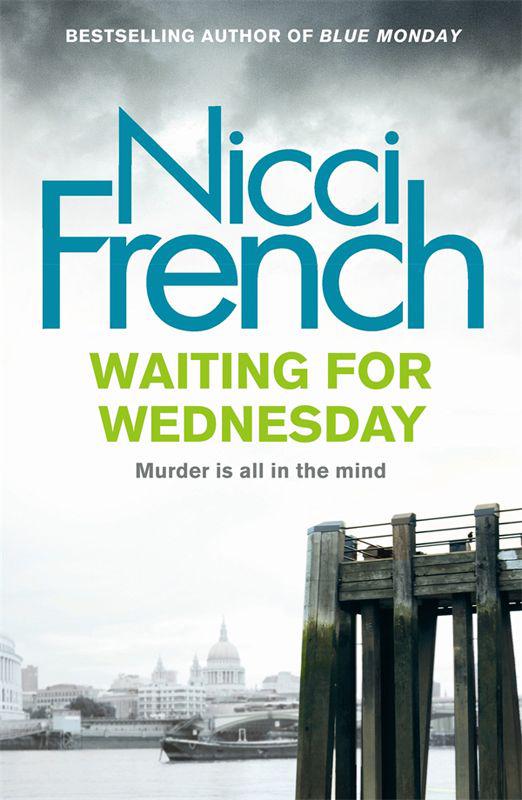

Waiting for Wednesday

to have some

tea.’

He led Frieda through the house. It was

clearly the home of a man – a very organized man – living alone. Through a door she saw

a large flat-screen TV and rows of DVDs on shelves. There was a computer. Underfoot was

a thick cream-coloured carpet, so that all the sounds were muffled.

Five minutes later they were standing on the

back lawn, holding mugs of tea. The garden was much larger than Friedahad expected, going back thirty, maybe forty, metres from the house. There was a neat

lawn with a curved gravel path snaking through it. There were bushes and flowerbeds and

little flashes of colour: crocuses, primroses, early tulips. The far end of the garden

was wilder and beyond it was a large, high wall.

‘I’ve been trying to tidy things

up,’ said Dawes. ‘After the winter.’

‘It seems pretty tidy to me,’

said Frieda.

‘It’s a constant struggle. Look

over there.’ He pointed to the garden next door. It was full of long grass,

brambles, a ragged rhododendron, a couple of ancient fruit trees. ‘It’s some

kind of council house. There’ll be a family of Iraqis or Somalians. Nice enough

people. Keep themselves to themselves. But they stay a few months and move on. A garden

like this takes years. Do you hear anything?’

Frieda moved her head. ‘Like

what?’

‘Follow me.’

Dawes walked along the path away from the

house. Now Frieda could hear a sound, a low murmuring that she couldn’t make out,

like a muttered conversation in another room. At the end of the garden, there was a

fence and Frieda stood next to Dawes and looked over it. With an improbability that

almost made her laugh, she saw that there was dip on the other side and in the dip a

small stream trickled along the end of the garden with a path on the other side, then

the high wall she had already seen. She saw Dawes smiling at her surprise.

‘It makes me think of the

children,’ he said. ‘When they were small, we used to make little paper

boats and put them on the stream and watch them float away. I used to tell them that in

three hours’ time, those boats would reach the Thames and then, if the tide was

right, they’d float out to sea.’

‘What is it?’ asked Frieda.

‘Don’t you know?’

‘I’m from north London. Most of

our rivers were buried long ago.’

‘It’s the Wandle,’ said

Dawes. ‘You must know the Wandle.’

‘I know the name.’

‘It rises a mile or so back. From here

it goes past old factories and rubbish dumps and under roads. I used to walk along the

path beside it, years ago. The water was foamy and yellow and it stank back then. But

we’re all right here. I used to let the children paddle in it. That’s the

problem with a river, isn’t it? You’re at the mercy of everybody who’s

upstream from you. Whatever they do to their river, they do to your river. What people

do downstream doesn’t matter.’

‘Except to the people

further

downstream,’ said Frieda.

‘That’s not my problem,’

said Dawes, and sipped his tea. ‘But I’ve always liked the idea of living by

a river. You never know what’s going to float by. I can see you like it

too.’

‘I do,’ Frieda admitted.

‘So what do you do, when you’re

not looking for lost girls?’

‘I’m a

psychotherapist.’

‘Is it your day off?’

‘In a way.’ They turned and

walked back down the garden. ‘What do you do?’

‘I do this,’ said Dawes.

‘I do my garden. I do up the house. I do things with my hands. I find it

restful.’

‘What did you do before

that?’

He gave a slow smile. ‘I was the

opposite, the complete opposite. I was a salesman for a company selling photocopiers. I

spent my life on the road.’ He gestured to Frieda to sit down on a wrought-iron

bench. He sat on a chair close by. ‘You know, there’s an expression I never

understood. Whenpeople say something’s boring, they say,

“It’s like watching grass grow.” Or “It’s like watching

paint dry.” That’s exactly what I enjoy. Watching my grass grow.’

‘I’m really here,’ said

Frieda, ‘because I’d like to find your daughter.’

Dawes put his mug down very carefully on the

grass next to his foot. When he turned to Frieda, it was with a new intensity.

‘I’d like to find her as well,’ he said.

‘When did you last see her?’

There was a long pause.

‘Do you have children?’

‘No.’

‘It was all I wanted. All of that

driving around, all that work, doing things I hated – what I

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher