![What became of us]()

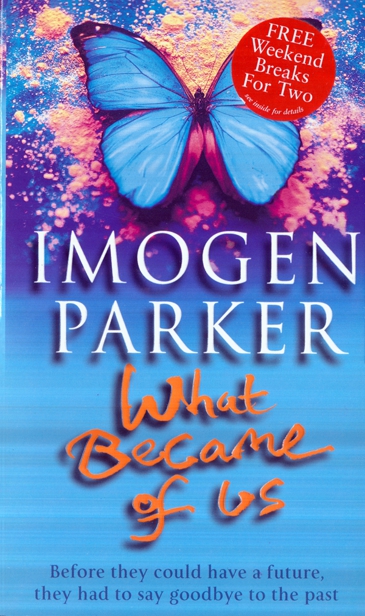

What became of us

patio and it lit straight away, which was something he had never achieved before and that made him feel absurdly triumphant. He went inside to look in the fridge. There were several packets of organic sausages and a large clingfilmed bowl of marinating chicken pieces. On the vegetable shelf was a tray of wooden kebab sticks threaded with pieces of red pepper, mushrooms and cherry tomatoes.

It was good for the girls to eat fresh food. He had lost count of the times he had taken them to McDonald’s because they refused to eat the undercooked pasta or leathery omelettes he had prepared for them, but he knew that they both were proud owners of the entire McDonald’s World Snoopy collection, and were impatient for the next promotion.

There were few occasions when they talked openly about missing their mother, but her absence was ever present at mealtimes. When he asked them what the difference was between the chips he put in the oven and those that Mummy cooked, the reply was always the same.

‘Mummy’s tasted nicer.’

He found mealtimes debilitating, but for some reason barbecue was different. Daddies were supposed to do barbecues and even sausages that were burnt on the outside and still cold and pink in the middle were pronounced delicious.

He wondered whether it was too early to start the cooking. He decided to anyway. He needed something to do to stop himself thinking.

He was manoeuvring a chicken thigh onto the grill when a loud, ‘Yoohoo!’ a couple of yards behind him made him jump. The tongs snapped shut, the chicken slithered between the wires and onto the charcoal with a subdued sizzle.

‘I’ve been ringing the doorbell for hours!’ said Annie coming round the side of the house, ducking under the hanging basket of petunias outside the kitchen door.

It was the first occasion he had ever felt positively glad to see her. There was no peace to think when Annie was around.

‘Took far less time to get here than I thought,’ she said. ‘Where is everyone?’

‘At church,’ he replied.

‘Church? Oh well.’ She inspected the containers of raw food, then stole a cherry tomato and popped it into her mouth. ‘Apparently they’re wonderful at preventing cancer,’ she said, ‘so I try to have one for every cig I smoke. Oops, sorry!’

‘It’s OK. I don’t know why nobody’s supposed to say the word,’ he said.

‘It’s because illness is contagious. I don’t mean literally. What I mean is, well, you don’t want to name cancer, because if you talk about it, it means it exists, and if it exists then there’s a possibility that you might get it.’

Roy raised an eyebrow sceptically.

‘That’s why people go on about standing up to it,’ Annie continued. ‘The reasoning goes like this: if you’re brave enough, then the cancer will take fright and go away. So, conversely, it’s your fault if you die. And if it’s your fault, not the illness’s, then that’s quite comforting for anyone else who might get it. Do you see?’

‘That’s an interesting view of the psychology,’ he said.

‘Of course I don’t think that: rationally I don’t anyway. But I’m as bad as anyone else when it comes to talking about it. That’s a long way round of saying sorry I’ve been so useless, by the way,’ she said, looking at him through big round apologetic eyes.

‘What do you mean?’ he enquired.

‘Well, you haven’t exactly seen much of me since Penny was ill, have you?’

‘No, but we never did before,’ he said.

Annie had been feeling so guilty, she had forgotten about that. Their lives had gone their separate ways long before Penny’s illness. First Penny had been in Africa, and then when Annie was a waitress and Penny a teacher, they didn’t seem to have much in common any more. Whenever she had visited Joshua Street, Penny would enthuse about the latest ragrolling techniques and stencilling, and Annie would give slightly exaggerated accounts of snorting cocaine and dancing at the Fridge. Annie was always in love with a different man, Penny pined chastely for Vin, then met up with Roy.

Actually, it was no wonder she hadn’t asked her to be godmother, Annie thought.

Her face brightened. She put a half-pepper in her mouth and crunched.

‘Healthy food. Fantastic! I’ve been eating like a student since I got here. I couldn’t make myself a cup of coffee, could I? Fm knackered. Only about two hours’ sleep, woken up by your bloody sister.’

‘Where is Ursula?’

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher