![What became of us]()

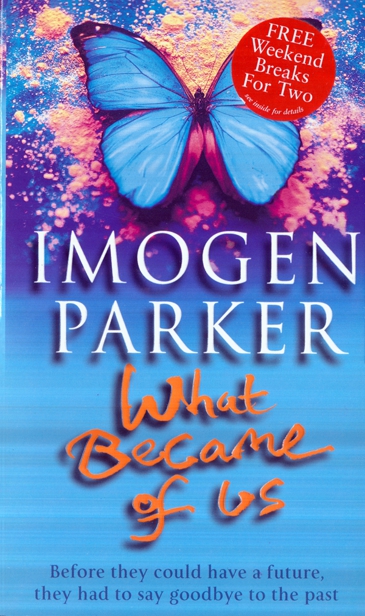

What became of us

she did not believe it. Her condition had nothing to do with the flimsy plastic wand in her hand, but she stared at it as if it were somehow responsible: first angry, then ridiculously grateful, and then preoccupied by the purely practical question of what you were supposed to do with it afterwards. She did not want to throw it away. Wiping the wand with toilet paper, she tried to get it back into the slim cardboard box it had come from, then impatiently shoved the whole lot back into the flimsy Boots bag.

A queue had already formed at the hat check desk, and with his usual vigilance, Cosmo, the club manager, had noticed her absence. As she passed him on the stairs she saw his eyes check the plastic carrier bag in her hand. She mouthed sorry at him as she wriggled past the line and ducked under the stable door, almost upsetting the saucer of tips. He nodded at her significantly. The only qualification for being the hat check girl was being there, and she was running a risk by taking an unscheduled break. If she wasn’t careful, Cosmo would have an excuse to promote her to front desk, as he was always offering to do, and although the money was better she did not want the job.

Manon liked the tiny room halfway up the stairs where she sat and watched London’s media world go by. In winter, the smell of wool, cigarettes and perfume that damp coats released as they steamed gently over the radiator, reminded her of her mother’s cupboard at home where she had hidden as a child and felt safe. In summer, she enjoyed brief proprietorship over tissue-wrapped designer clothes that nestled inside Day-Glo cardboard sale bags. At Easter, someone had asked her to look after a rabbit in a basket tied with yellow ribbon, and recently a celebrity mother had handed over her sleeping baby while she gave a press conference in one of the function rooms upstairs. The only thing that people never seemed to check in was hats. With tips, the money was enough. She got by. She liked the anonymity of it. She had no responsibilities except to sit there.

She dealt with the queue. People seemed to be looking at her oddly. She realized it was because she was smiling. She could not help it. She had a secret, a tiny secret that no-one else in the whole world knew about. Her secret was her companion. For the first time in a very long time she did not feel alone in the world.

During the lull, when after-work drinkers had departed and diners were taking up their tables in the restaurant, Manon picked up the splayed paperback beside her and tried to concentrate but the words would not keep still. She was excited. She could feel her heartbeat in her chest. All her senses seemed to have woken up, and still she was smiling, even though there was nobody around to smile at. She read a page twice, realizing that she had still not taken in what it said, and then a voice made her jump. She had not heard the street door opening, or the footsteps on the wooden stairs.

‘Hey, baby.’

‘Frank...’

‘Can you look after this for me?’

He handed her a tied bunch of flowers that looked and smelt like a clump of summer meadow. There were cornflowers, dandelions, pale green ears of wheat and field poppies, the petals miraculously staying put when instinctively she touched them to discover if they were real. The florist’s label was the same as the one that had been attached to the last bouquet he had bought her — a hundred roses packed together in a hemisphere, the colour graduating from velvety black crimson at the circumference to a single rose at the centre so delicate a pink it was almost white and smelling as she imagined heaven must smell. She hated it when flowers died, she had told him then, wanting to put him off buying another bouquet. She much preferred to see them growing in a field. And so he had brought her the field, which was typical of the way he misunderstood her.

Why, he would sometimes ask her, why won’t you accept things from me? Why won’t you let me buy you some decent clothes or get you a proper job? Because of the way you’re looking at me, she would think, because you think I can be bought. But she never replied, because it was pointless to argue with him. He was good at arguments, but he would not change what she felt. It would not be enough for him to hear that she did not want wild flowers to die for her, or ruby earrings in a blue Tiffany’s box tied with white silk ribbon. He would argue that her position was

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher